Russia’s objective in asymmetric warfare is to avoid direct military operations while interfering in the internal conflicts in other countries. In a 2003 article for the Russian-language journal International Trends, Victor Kremenyuk laid out the specifics of fighting weaker adversaries relying on the following strategy:

- Employ small units of specially trained troops.

- Take preventive actions against irregular enemy forces.

- Spread propaganda among local populations.

- Provide military and material support to friendly groups in the country being attacked.

- Scale back combat operations.

- Employ nonmilitary methods to pressure the opponent.

As Putin put it in 2006, “We should not go after quantity. Our responses must be based on intellectual superiority. They will be asymmetrical, not as costly, but will unquestionably make our nuclear triad more reliable and effective.”

Asymmetrical Strategies & Tactics

Chekinov and Bogdanov describe the main instruments of asymmetric warfare employed by Russia as including, but not limited to:

- Measures making the opponent apprehensive of the Russian Federation’s intentions and responses.

- Demonstration of the readiness and potential of the Russian forces in a strategic area to repel an invasion with consequences unacceptable to the aggressor.

- Actions by Russian forces to deter a potential enemy by guaranteeing destruction of his most vulnerable military and strategically important targets to persuade him that an attack is hopeless.

- Impact of highly effective, state-of-the-art weapons systems.

- Widespread employment of indirect force and non-contact commitment of forces.

- Seizing and holding enemy territory only undertaken if the benefits are greater than the combat costs, or if the end goals of the war cannot be achieved any other way.

- Information warfare as an independent form of combat along with economic, political, ideological, diplomatic forms.

- Information and psychological operations to weaken the enemy’s military potential by other than armed force, by affecting his information flow processes, and by misleading and demoralizing the population and enemy military personnel.

- Significant damage to the enemy’s future economic potential.

- A clear understanding by a potential adversary that military operations against Russia may turn into an environmental and sociopolitical catastrophe.

- Strategy to deal with states and regions on the periphery of the Russian Federation.

- Primacy of nonmilitary factors: politics, diplomacy, economics, finance, information, and intelligence.

- Primacy of the information domain: use of cyberwarfare, propaganda, and deception, especially toward the Russian-speaking populace.

- Persistent (rather than plausible) denial of Russian operations.

- Use of unidentified local and Russian agents.

- Use of intimidation, bribery, assassination, and agitation.

- Start of military activity without war declaration; actions appear to be spontaneous actions of local troops/militias.

- Use of armed civilian proxies, self-defense militias, and imported paramilitary units (e.g., Cossacks, Vostok Battalion) instead of, or in advance of, regular troops.

- Asymmetric, nonlinear actions.

In the field, this strategy means employing high precision non-nuclear weapons, together with the support of subversive and reconnaissance groups. Strategic targets are those that, if destroyed, result in unacceptable damage for the country being attacked. According to Chekinov and Bogdanov, these include top government administration and military control systems, major manufacturing, fuel and energy facilities, transportation hubs and facilities (such as railroad hubs, bridges, ports, airports and tunnels), and potentially dangerous objects (hydroelectric power dams and hydroelectric power complexes, processing units of chemical plants, nuclear power facilities, storages of strong poisons and so forth).

Russia’s objective is to make the enemy understand that it may face an environmental and sociopolitical catastrophe, and therefore avoid engaging in combat.

These are the key elements of Russian new generation warfare. It combines direct/symmetrical actions with asymmetrical instruments, aiming to achieve the tactical objectives established by political leaders. Since the Russians understand they are not strong enough to win a war against NATO, their strategy relies on asymmetric methods. Most important is that this strategy is based on attacking an adversary’s weak points. As a result, each campaign is unique.

In his recent work entitled The Technology of Victory, Igor Panarin, a leading advocate for Russian information warfare, boasted about the nearly flawless Russian operation to seize and annex Crimea. He celebrated the campaign’s success in avoiding armed violence and preempting American interference. While pointing to neoconservative ideals of justice, spirituality, and true liberty, he praised the use of blackmail, intimidation, and deception in the face of international dithering in the West. He attributed the success to the personal leadership and direct control of Vladimir Putin.

Asymmetrical Information Warfare

According to Russian doctrine, information is a dangerous weapon. “It is cheap, it is a universal weapon, it has unlimited range, it is easily accessible and permeates all state borders without restrictions.” – Jolanta Darczewska

Western militaries tend to look upon what they refer to as information operations merely as an adjunct to their campaign plans. In contrast, for Russian military thinkers, information now has primacy in operations, while more conventional military forces are in a supporting role. The Latvian analyst Janis Berzins observes how this new Russian emphasis on information has changed the focus in today’s major conflicts from direct destruction to direct influence, from a war with weapons and technology to information or psychological warfare.

Thus the Russian view of modern warfare is based on the idea that the main battlespace is in the mind and, as a result, new-generation wars are to be dominated by information and psychological warfare with the main objective [being] to reduce the necessity for deploying hard military power to the minimum necessary, making the opponent’s military and civil population support the attacker to the detriment of their own government and country.

As Berzins makes clear, from the Russian perspective, modern warfare is to be fought in the mind and information will be the principal tool in this fight, creating a version of reality that suits political and military purposes at all levels of warfare.

Information warfare consists in making an integrated impact on the opposing side’s system of state and military command and control and its military-political leadership an impact that would lead even in peacetime to the adoption of decisions favorable to the party initiating the information impact, and in the course of conflict would totally paralyze the functioning of the enemy’s command and control infrastructure. – Russian information warfare theorist Col. P. Koayesov

Russian information warfare techniques are an amalgamation of (1) methods evolved within the Soviet Union (with roots as far back as tsarist Russia) and (2) deliberate developments in response to scrutiny of Western, especially American, operations in the twenty-first century. The revitalized doctrine, called spetzpropaganda, is taught in the Military Information and Foreign Languages Department of the Military University of the Ministry of Defense. As an academic discipline it reaches out to military personnel, intelligence operatives, journalists, and diplomats.

In general, Russian information warfare has in view the broad Russian-speaking diaspora that fragmented into the various post-Soviet era states. It aims at affecting the consciousness of the masses, both at home and abroad, and conditioning them for the civilizational struggle between Russia’s Eurasian culture and the West. The “Spetzpropaganda” doctrine specifies that an information campaign is multidisciplinary and includes:

- Politics

- Economics

- Social dynamics

- Military

- Intelligence

- Diplomacy

- Psychological operations

- Communications

- Education

- Cyberwarfare

At its roots, the theory is military and nonmilitary, technological and social. Information warfare is likewise the chief tool with which the state achieves diplomatic leverage and attains its foreign policy goals. It links directly to geopolitics in service to the state and the Russian civilization. Through coordinated manipulation of the entire information domain (including newspapers, television, Internet websites, blogs, and other outlets), Russian operatives attempt to create a virtual reality in the conflict zone that either influences perceptions or (among some Russian-speaking audiences) replaces actual ground truth with pro-Russian fiction.

The Gerasimov Model

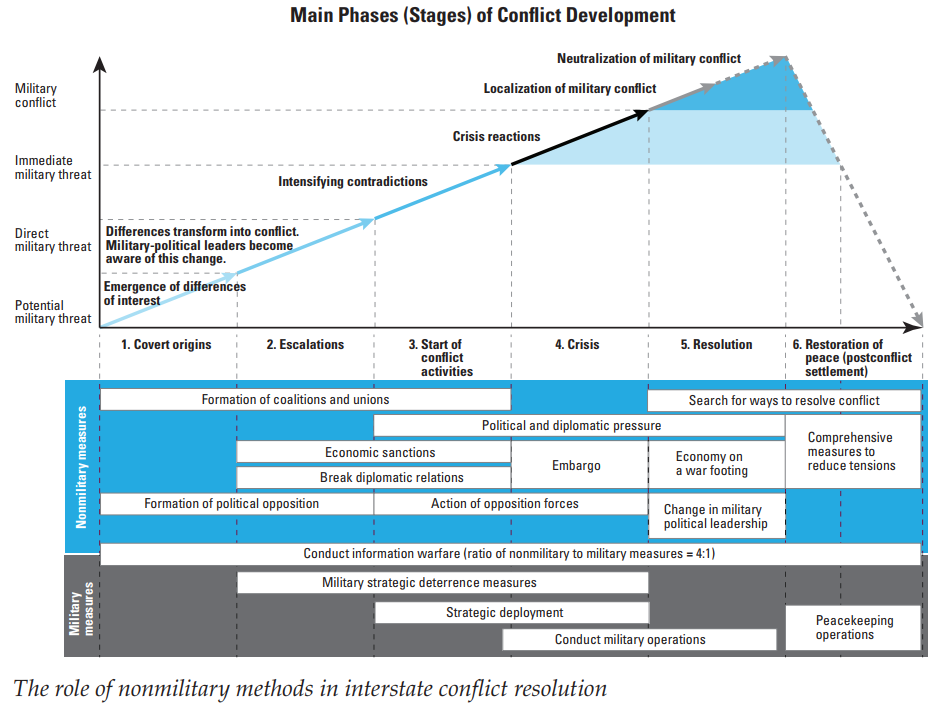

Russian Chief of Staff Valery Gerasimov’s model for interstate conflict reflects the growing importance of non-kinetic factors in Russian strategy.

This study uses an analytical framework derived from the work of General Valery Gerasimov, chief of the general staff of the Russian Federation. General Gerasimov’s main thesis is that modern conflict differs significantly from the paradigm of World War II and even from Cold War conflict. In place of declared wars, strict delineation of military and nonmilitary efforts, and large conventional forces fighting climactic battles, modern conflict instead features undeclared wars, hybrid operations combining military and nonmilitary activities, and smaller precision-based forces. Gerasimov, observing American and European experiences in the Gulf War, Operation Iraqi Freedom, and the intervention in Libya, notes that political, economic, cultural, and other nonmilitary factors play decisive roles. Indeed, even humanitarian operations should be considered part of an unconventional warfare campaign.

In a January 2013 report entitled The Main Trends in the Forms and Methods of the Armed Forces Gerasimov explained that the Color Revolutions and the Arab Spring demonstrated that the line between war and peace has blurred. While liberal democratic uprisings may not appear to constitute war, they often result in foreign intervention (both overt and clandestine), chaos, humanitarian disaster, and civil war. These activities may become the typical war of the modern era, and Russian military practices must evolve to accommodate the new methods.

Modern War, Gerasimov Argued, Focuses On Intelligence & Domination Of The Information Space

Information technologies have reduced the spatial, temporal, and information gap between army and government. Objectives are achieved in a remote contactless war; strategic, operational, and tactical levels, as well as offensive and defensive actions, have become less distinguishable. Asymmetric action against enemy forces is more commonplace. Gerasimov developed a model for modern Russian warfare under the title The Role of Nonmilitary Methods in Interstate Conflict Resolution. His model envisions six stages of conflict development, each characterized by the primacy of nonmilitary measures but featuring increasing military involvement as the conflict approaches resolution.

Six Stages Of Conflict Development

- Covert origins: During the initial stage, which will likely be protracted, political opposition forms against the opposing regime. This resistance takes the form of political parties, coalitions, and labor/trade unions. Russia employs strategic deterrence measures and conducts a broad, comprehensive, and sustained information warfare campaign to shape the environment toward a successful resolution. At this stage, the potential for military activity emerges.

- Escalations: If the conflict escalates, Russia exerts political and diplomatic pressure on the offending regime or non-state actors. These activities can include economic sanctions or even the suspension of diplomatic relations to isolate the opponent. During this stage military and political leaders in the region and abroad become aware of the developing conflict and stake out their public positions.

- Start of conflict activities: The third stage begins as opposing forces in the conflict region commence actions against one another. This can take the form of demonstrations, protests, subversion, sabotage, assassinations, and paramilitary engagements. Intensification of conflict activities begin to constitute a direct military threat to Russian interests and national security. At the commencement of this stage of conflict, Russia begins strategic deployment of its forces toward the conflict region.

- Crisis: As the crisis comes to a head, Russia commences military operations, accompanied by strong diplomatic and economic suasion. The information campaign continues with a view to rendering the environment conducive to Russian intervention.

- Resolutions: During this stage Russian leadership searches for the best paths to resolve the conflict. The domestic economy is on a war footing, as a way to unify the nation’s efforts toward successful prosecution of the war effort. A key aspect of resolution is effecting a change in the military and political leadership of the conflict region or state what Western militaries refer to as regime change. The goal is to reset the political, military, economic, and social reality in the region in such a way as to facilitate a return to peace, order, and the resumption of routine relations.

- Restoration of peace (post-conflict settlement): During the final stage, which again may be protracted, Russia oversees comprehensive measures to reduce tensions and conducts peacekeeping operations. This stage includes the diplomatic and political measures required to establish a post-conflict settlement that addresses the original causes of conflict.

Gerasimov’s Model For Modern Conflict

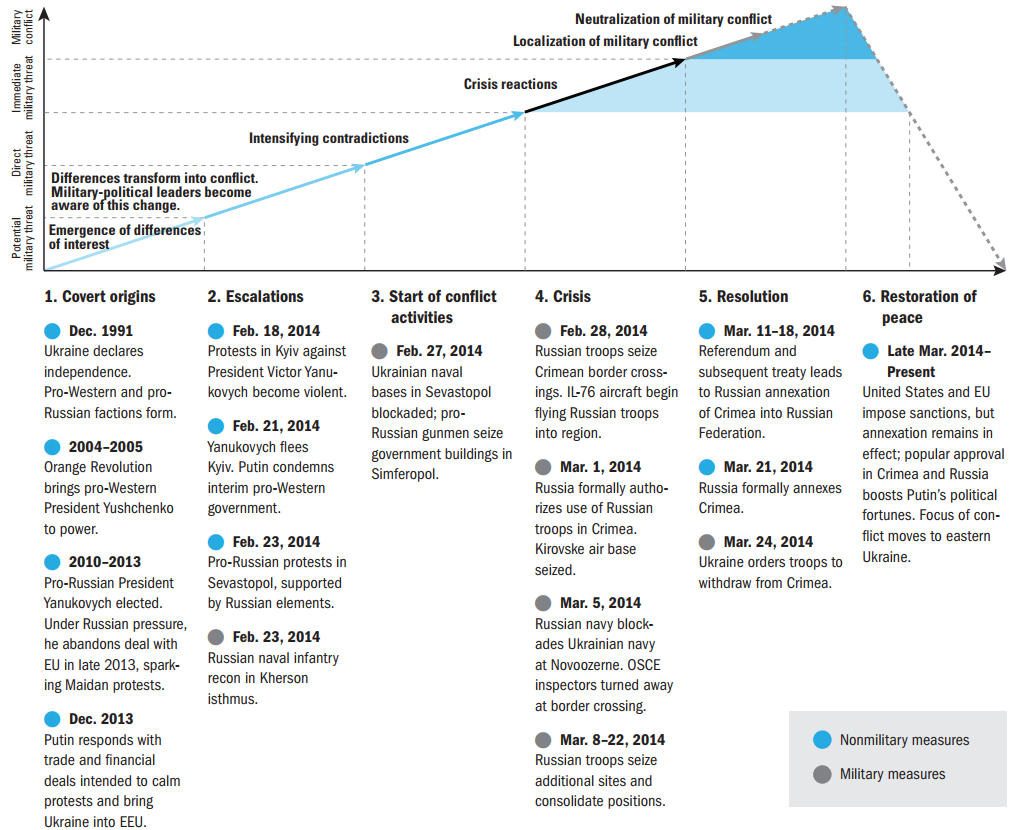

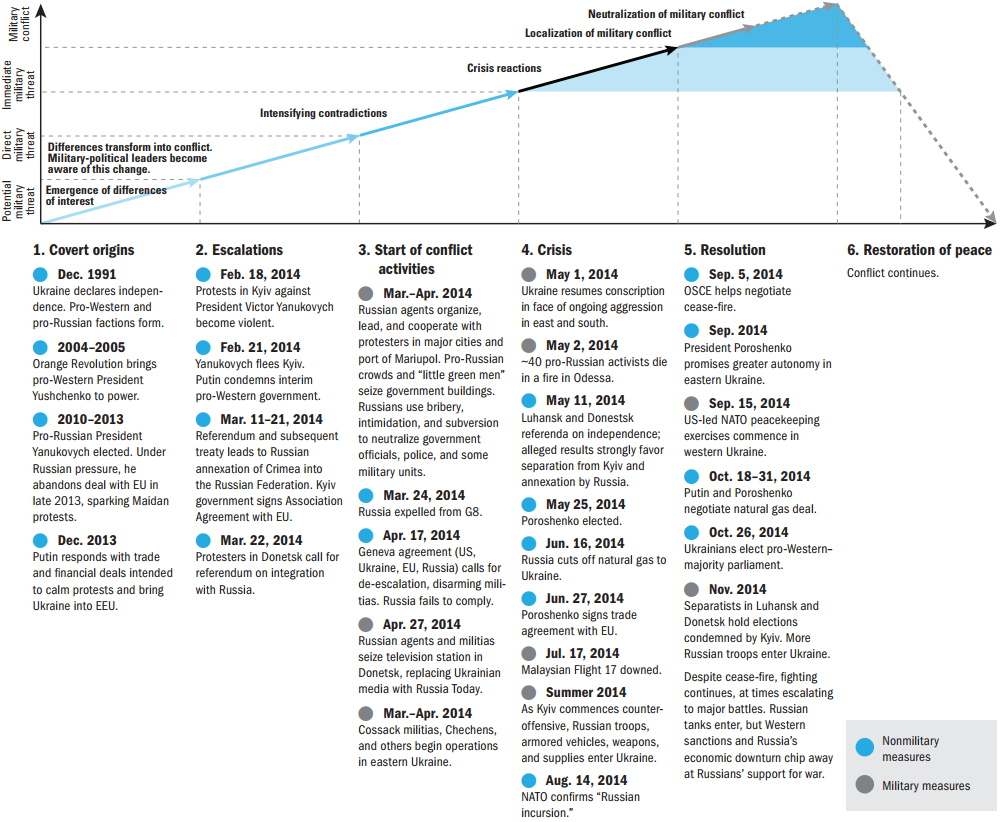

Gerasimov’s model for modern conflict is a theoretical adaptation of emerging ideas about warfare, but elements of these ideas clearly pertain to Russia’s unconventional warfare in Ukraine and Crimea in 2013-2014.

Gerasimov’s Model in Crimea:

Six Stages Of Conflict Development: Crimea

- Covert origins: The covert origins stage featured a long period of political infighting in Kyiv, culminating in an unforeseen crisis for Putin.

- Escalations: During the escalations stage Putin took actions calculated to de-escalate the situation, but they had the opposite effect.

- Start of conflict activities: The start of conflict activities was relatively sudden and brief, quickly transitioning to the next stage. This suggests intensive and deliberate planning designed to preempt any embryonic resistance forming against Putin’s designs.

- Crisis: The crisis stage featured nearly flawless execution of Russia’s new information-based warfare, culminating in a staged referendum and political decision.

- Resolutions: During the resolutions stage, Putin’s autocratic government rapidly sealed the annexation with a legal form. With Russian troops firmly in control of Crimea, he was able to present the world with a fait accompli.

- Restoration of peace (post-conflict settlement): The restoration of peace stage was facilitated in part by the upswing of conflict in eastern Ukraine, so as to divert attention away from Crimea.

Gerasimov’s Model in Eastern Ukraine:

- Covert origins: The covert origins stage featured a long period of political infighting in Kyiv, culminating in an unforeseen crisis for Putin.

- Escalations: During the escalations stage Putin took actions calculated to de-escalate the situation, but they had the opposite effect. The March 2014 annexation of Crimea led to an upswing of unrest in eastern Ukraine.

- Start of conflict activities: The start of conflict activities was framed by Russia’s deceptive diplomatic agreement at Geneva setting the stage for Putin’s sustained unconventional warfare campaign in eastern Ukraine under an umbrella of persistent denial.

- Crisis: The crisis stage came to a head with the downing of Malaysian Airlines Flight 17, which fueled growing international condemnation of Putin’s intervention in Ukraine.

- Resolutions: The hoped-for resolutions stage instead saw surprising political resilience from the Kyiv government and people of Ukraine against Russian aggression. US, EU, and NATO support, along with Russia’s severe economic downturn and President Poroshenko’s sustained counteroffensive, led Russia to resort to increasingly explicit invasion.

- Restoration of peace (post-conflict settlement): The restoration of peace stage remains in doubt as the US government passes a renewed sanctions law and threatens to begin giving military aid to Kyiv.

Conclusion

Russian unconventional warfare and Moscow’s innovative approaches to IO largely succeeded in the recent annexation of Crimea. Nonetheless, Russia’s intervention in eastern Ukraine experienced difficulties, leading to an extended conflict. While the current outcome for the Russians is mixed, it is clear that Russian leaders have absorbed the painful lessons of their post-Cold War setbacks, most notably those in Georgia in 2008. Over time they have observed and adjusted to American moves during the Color Revolutions and the 2010 Arab Spring. By viewing US foreign policy initiatives through the lens of geopolitics, Russian neoconservatives have embraced an aggressive foreign policy designed to reverse the losses associated with the collapse of the Soviet Union, especially along the Russian periphery. Driven by a desire to roll back Western encroachment into the Russian sphere of influence, the current generation of siloviki have crafted a multidisciplinary art and science of unconventional warfare. Capitalizing on deception, psychological manipulation, and domination of the information domain, their approach represents a notable threat to Western security interests.

The United States needs a national acceptance and understanding that it is engaged in an Asymmetric War. The nation must mobilize its industry and population. Federal government departments are only the beginning of the human resources and expertise needed to win over a target population. Local experts on such services as law enforcement, sewage, education and electricity just to name a few are also crucial. During World War II, this nation’s industry rallied behind the war effort. In a war of ideas where information operations are so important, why are the brightest minds in the United States focused on convincing more young Americans to prefer one soft drink over another, or convincing more voters in the Midwest to vote for one party over the other? How many Wharton marketing MBAs or Harvard political analysts are trying to show the young Muslim population of the world that U.S. interests do not conflict with their religious beliefs? That the United States is a secular society that makes no religious judgment? That working with the United States is greatly within their material interests? That the United States simply wishes to rebuild their country into greatness rather to than exploit it looking at Germany and Japan as examples? And finally, that the enemy seeks only to build his own power at the cost of young Muslim lives and suffering? The brightest minds of the enemy are convincing them of the opposite…

The major threat to Western interests anywhere in the world is not terrorism, it is the threat posed by information warfare such as that recently conducted by Russia. It has achieved clear results and this success can be repeated. As NATO finds it almost impossible to react effectively in a symmetrical fashion to this threat, it has felt the need to resort to more traditional means. Yet these are responses that are better suited to the last war. Unlike the Russian military, NATO is still putting the use of military force ahead of information warfare because as an institution it knows no other way of reacting.

This is a unique opportunity to make smart and targeted investments in technologies suited for low-intensity military operations that will continue to be a staple of future conflicts. There are big strategic and military challenges for America, particularly in the Pacific with China and in Eastern Europe with Russia. As history has shown, Asymmetric Warfare is not going away and if anything, it is only going to get more dangerous and more disruptive.

Thanks for reading!