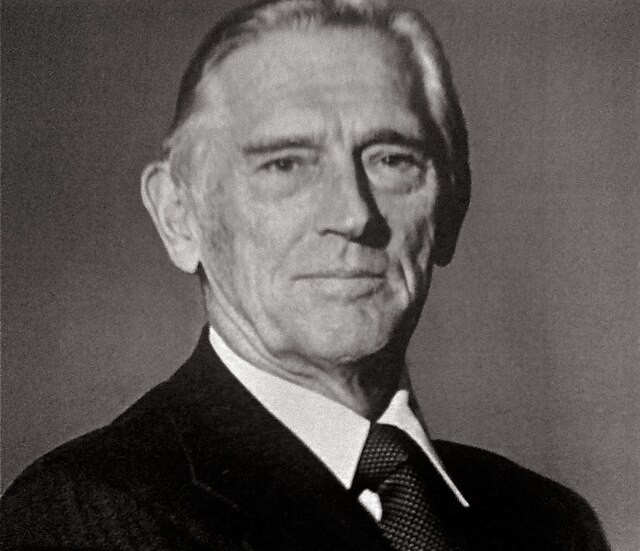

In the landscape of economic foresight, few concepts have captured the hierarchy of financial risk as elegantly as Exter’s Inverted Pyramid. Created by economist John Exter in the 1970s, this visual framework has proven remarkably prescient in predicting financial crises and understanding how capital flows during economic cycles. Today, as we navigate an era of unprecedented monetary expansion and debt accumulation, Exter’s insights are more relevant than ever.

From Central Banker To Gold Advocate: The John Exter Story

John Exter’s journey from establishment insider to contrarian gold advocate is a remarkable tale of intellectual independence. Born in 1910, Exter lived through the 1929 stock market crash and the Great Depression, experiences that would shape his lifelong quest to understand economic catastrophes.

His career reads like a who’s who of global finance. After graduating from the College of Wooster and the Fletcher School of Law & Diplomacy, Exter earned his economics degree from Harvard in 1939. During World War II, he worked at MIT’s Radiation Laboratory before joining the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System as an economist.

In 1948, Exter’s expertise in monetary systems led him to advise the Secretary of Finance of the Philippines and the Minister of Finance of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) on establishing central banks. He became the founding governor of the Central Bank of Ceylon from 1950 to 1953, where his “Report on the Establishment of a Central Bank for Ceylon” continues to be studied by central bankers today.

Returning to the United States, Exter joined the Federal Reserve Bank of New York in 1954 as vice president in charge of international banking and gold and silver operations. This position gave him an intimate view of the global monetary system’s inner workings—and its growing vulnerabilities.

By 1962, Exter had become deeply concerned about monetary expansion. He watched as President Kennedy pressured Fed Chairman William McChesney Martin to expand the money supply, and saw the Fed become “a hopeless prisoner of its own expansionism.” Reserve Bank credit grew from $25 billion in 1961 to $290 billion by 1991—a staggering 1,160% increase.

Recognizing the implications, Exter began buying gold at $35 an ounce. Americans were prohibited from owning gold bullion, but the Treasury had declared gold sovereigns to be “rare coins.” Exter could buy these sovereigns for about $36 an ounce. By 1968, he had moved to a 100% gold position—a decision that would prove spectacularly profitable.

When President Nixon closed the gold window on August 15, 1971, Exter was 60 years old. Rather than spend another four years at what would become Citibank, he took early retirement to become a private consultant. He had seen enough to know that the global monetary system had fundamentally changed, and not for the better.

In 1970, Exter co-founded the Committee for Monetary Research and Education (CMRE) alongside economists Henry Hazlitt, Jacques Rueff, and Robert Triffin. Their collective concern about the Bretton Woods system’s impending collapse proved prescient just one year later.

From Bretton Woods To Fiat: The 1971 Turning Point

The closing of the gold window on August 15, 1971, represents one of the most significant monetary events in human history. As Exter repeatedly emphasized, it marked the first time the entire world operated on an unbacked paper money system. No longer could foreign central banks exchange their dollar reserves for gold at $35 per ounce. The age of pure fiat currency had begun.

Exter understood immediately what this meant. While at Citibank, he made presentations explaining that the world had moved to floating exchange rates with no stable anchor. His warnings fell on deaf ears.

The establishment’s response was telling. At the Smithsonian Conference in December 1971, the world’s monetary authorities—including Fed Chairman Arthur Burns, Treasury Undersecretary Paul Volcker, and Treasury Secretary John Connally—attempted to re-establish fixed exchange rates without gold backing. Exter called this “a giant exercise in futility.”

He was right. By January 1973, while visiting Zurich, Exter met with Swiss central bank president Fritz Leutwiler, who confided that he would have to stop buying dollars to maintain the fixed rate. The Smithsonian Agreement had lasted barely a year.

This transition from gold-backed money to pure fiat currency set the stage for decades of credit expansion. As Exter noted, “Without central banks, such a catastrophe could not be possible.” He pointed to historical precedents: John Law’s system in France, America’s Continental dollar, and the French Revolutionary assignat—all had collapsed. In his own lifetime, he had witnessed two German currencies become worthless.

The implications were staggering. Banks like Citibank grew from $15 billion in 1959 to $230 billion by the 1990s—a 1,533% increase. The recycling of petrodollars, where banks accepted short-term deposits from oil producers and made long-term loans to developing countries, exemplified the dangerous practices enabled by unlimited fiat money creation.

Exter’s Pyramid Explained: A Visual Guide To Understanding Financial Risk

Exter’s Inverted Pyramid stands on its apex—a small point of gold that supports an enormous superstructure of increasingly risky assets. This design brilliantly illustrates both the hierarchy of financial assets and their relative sizes in the global economy. John Exter’s original pyramid of assets is shown in image below.

The Foundation: Gold

At the pyramid’s base (the narrow bottom of the inverted pyramid) sits gold. Exter chose gold not out of tradition but because it uniquely combines several critical characteristics:

- No counterparty risk (doesn’t depend on anyone’s promise to pay)

- No credit risk (can’t default or go bankrupt)

- Highly liquid (accepted worldwide)

- Historically proven store of value

Moving Up the Pyramid

As we ascend the inverted pyramid, each layer represents assets that are progressively:

- Less liquid

- More dependent on counterparty performance

- Larger in total market size

- Riskier during financial stress

The modern interpretation of Exter’s Pyramid typically includes these layers:

Paper Money & Bank Deposits: Physical cash and checking accounts. While liquid and widely accepted, they depend on government backing and can be devalued through inflation.

Government Bonds & Treasury Bills: Debt backed by government’s ability to tax and print money. Considered “risk-free” in conventional finance, though Exter understood they carried inflation risk.

Municipal & Corporate Debt: Bonds issued by local governments and companies. These carry credit risk—the possibility that the issuer might default.

Stocks: Equity ownership in companies. More volatile than bonds and represent junior claims on corporate assets.

Real Estate & Commodities: Physical assets that can provide inflation protection but are less liquid and subject to market cycles.

Private Business Equity: Ownership stakes in non-public companies. Highly illiquid with significant business risk.

Derivatives & Securitized Debt: The pyramid’s apex (widest part), including options, futures, mortgage-backed securities, and complex financial instruments. These can have values in the quadrillions and represent claims on underlying assets many times over.

The Pyramid’s Crucial Insight

The inverted shape reveals a disturbing truth: the narrowest part (gold) must support an enormously wide superstructure of paper claims. This works during expansions when confidence is high, but becomes catastrophic when confidence fails and everyone tries to move down the pyramid simultaneously.

Reading The Pyramid: Where We Are In The Credit Cycle

Understanding Exter’s Pyramid provides a framework for recognizing where we are in the credit cycle and how capital flows during different economic phases.

During Credit Expansion

When confidence is high and credit is expanding:

- Capital flows UP the pyramid

- Investors seek higher returns in riskier assets

- The same capital gets reused multiple times (fractional reserve banking, margin trading)

- The pyramid broadens as derivatives and securitized products multiply

- Gold and safe assets are shunned as “barbarous relics”

During Credit Contraction

When confidence wanes and credit contracts:

- Capital flows DOWN the pyramid

- Investors flee to safety and liquidity

- Risky assets become illiquid (hard to sell at any price)

- The pyramid “pancakes” as values collapse

- Gold and government bonds outperform stocks

Key Indicators to Watch

Currency in Circulation: One of Exter’s most prescient observations was tracking physical cash demand. In 1989, currency in circulation increased $11 billion; by 1990, it jumped $27 billion. This cash wasn’t needed for transactions—it was being hoarded for safety. As Exter noted, “You don’t buy many things with cash other than groceries & gasoline.”

Credit Default Swaps: Modern investors can use credit default swap spreads as sensitive indicators of credit stress. Widening spreads signal deteriorating credit quality and potential capital flight down the pyramid.

Relative Performance: During credit stress, watch the relative performance of:

- Gold vs. stocks (gold outperforms during flight to safety)

- Long-term Treasury bonds vs. stocks (bonds outperform as credit quality deteriorates)

- Cash demand vs. bank deposits (rising cash demand signals fear)

The Supply/Demand Mismatch

The pyramid reveals a critical mathematical problem. When panic strikes, sellers of $100 trillion in global financial assets try to crowd into:

- $1.5 trillion in physical U.S. dollar cash

- $1.4 trillion in investable gold

- $1 trillion in long-dated Treasury bonds

This mismatch explains why gold prices can “go through the roof” during crises, as Exter predicted.

The Quadrillion Dollar Question: Derivatives & Exter’s Warning

At the top of Exter’s modern pyramid sits the derivatives market—a shadowy realm of financial instruments whose notional value reaches into the quadrillions. This represents the ultimate expression of leveraged paper claims divorced from real assets.

Exter’s original pyramid in the 1970s placed Third World debt at the top as the riskiest asset class. Today, derivatives have assumed this dubious honor, dwarfing all other financial markets combined. These instruments—options, futures, swaps, and increasingly complex variations—represent bets on bets, claims on claims, often leveraged many times over.

Warren Buffett famously called derivatives “financial weapons of mass destruction,” echoing Exter’s warnings about excessive leverage and interconnected risks. During the 2008 financial crisis, we saw how derivatives could freeze entire markets and threaten the global financial system.

The danger Exter identified is structural: each level of the pyramid depends on the levels below for support. Remove any lower level, and everything above collapses “like a Jenga tower.” When derivatives represent claims many times larger than the underlying assets, the potential for catastrophic deleveraging multiplies.

Exter understood that derivatives serve some legitimate purposes—hedging and price discovery—but warned that their explosive growth represented the ultimate expansion of credit without substance. In his framework, they are the antithesis of gold: maximum counterparty risk, minimum real value, and extreme illiquidity during crises.

Currency In Circulation: The Hidden Flight To Safety Signal

Perhaps Exter’s most practical insight for modern investors is his focus on currency in circulation as an early warning signal. This indicator, published weekly in financial newspapers, reveals when the public is quietly panicking.

Physical cash represents a peculiar position in the pyramid—it’s still fiat currency, subject to inflation and government manipulation, but it eliminates bank risk. When people pull cash from banks to store “under the mattress,” they’re instinctively moving down Exter’s Pyramid, even if they don’t realize it.

Exter documented this phenomenon in 1990-1991 when currency in circulation increased by $27-29 billion year-over-year, far exceeding the previous record of $13 billion. This cash wasn’t circulating—it was being hoarded. As he explained, people were “getting out of weak S&Ls, weak banks, weak insurance companies” and moving to physical currency.

The irony, which Exter clearly understood, is that people fleeing to paper money had the right instinct but the wrong destination. “It’s stupid for people to hold currency,” he said. “The Fed can simply print all they want at very low cost. Paper money is as abundant as leaves on trees.”

This observation provides a practical tool for modern investors:

- Monitor currency in circulation data for unusual increases

- Recognize that cash hoarding signals systemic fear

- Understand that such fear often precedes larger market disruptions

- Consider that if people are fleeing to paper, the next step is fleeing paper itself

The Pyramid’s Enduring Wisdom

Exter’s Inverted Pyramid remains remarkably relevant because it captures timeless truths about human nature, confidence, and the structure of financial systems. In our current era of unprecedented global debt, zero interest rates, and experimental monetary policies, his framework provides essential perspective.

The pyramid teaches us that:

- All paper assets ultimately depend on confidence

- In crises, liquidity becomes paramount

- The door to real safety (gold) is narrow

- Debt pyramids built on thin foundations eventually collapse

- Central banks enable but cannot prevent these cycles

As Exter warned in 1991, we face “the worst economic catastrophe in all of history” precisely because “the whole world has gone off gold.” Whether his dire prediction comes to pass or not, his pyramid provides a valuable framework for understanding financial risk and protecting wealth.

Final Thoughts

For investors, the lesson is clear: understand where your assets sit on Exter’s Pyramid, recognize the signs of credit cycle transitions, and never forget that when confidence fails, everyone rushes for the same narrow exit. In Exter’s words, “When they go to gold instead of currency or Treasury bills, the price of gold will take off. It will be a bandwagon everyone will want to get on.”

The pyramid stands as both warning and guide—a testament to one man’s intellectual independence and a roadmap for navigating the recurring cycles of credit expansion and collapse that define our modern financial system.

Thanks for reading!