T.L.D.R. –

- Age at Signing: 39

- Occupation: Planter

- Key Perspective/Position: Wealthy but reluctant

- Personal Sacrifice: Ships and fortune lost

- Unique Contribution: Funded Navy

Introduction

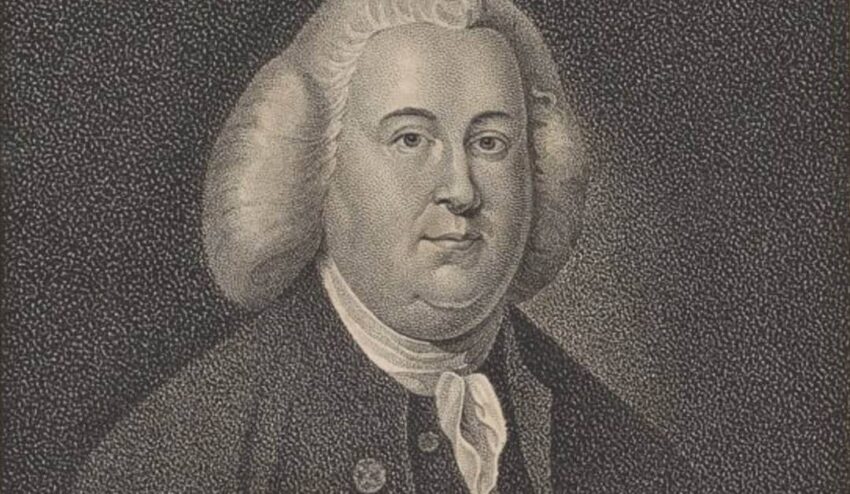

Carter Braxton was born on September 10, 1736, at Newington Plantation, Virginia. He graduated from William and Mary College in 1755 and at 19 married into another influential family, further elevating his status. After his first wife died after two years, leaving two daughters, he traveled to England to recover, becoming familiar with British politics. He remarried Elizabeth Corbin, and they had sixteen more children.

Returning to Virginia, Braxton resumed life as a planter and businessman. As tensions escalated, he joined the Virginia House of Burgesses. In 1776, he was appointed to the Continental Congress. Though initially reluctant, he supported independence and signed the Declaration, risking his vast wealth.

Braxton invested heavily in the Patriot cause, funding the Continental Navy and military efforts. Many of his ships were lost to British blockades and wartime destruction. Once one of Virginia’s wealthiest men, he took on tremendous debt. After the war, he served in the Virginia state government and died on October 10, 1797, at age 61, having sacrificed much of his fortune for American freedom.

Contribution to Independence: Braxton exemplified the wealthy patriots who risked everything. His financing of the Continental Navy and military efforts, despite devastating personal losses, demonstrated true sacrifice for the cause.

A Brief Biography

Carter Braxton was born on September 10, 1736 at Newington Plantation in Livingston, Virginia. He was the son of George Braxton, Jr. and of Mary Carter, who died just seven days after giving birth. Carter’s father died when he was in his teens, and he was raised by family friends.

Carter Braxton was born on September 10, 1736 at Newington Plantation in Livingston, Virginia. He was the son of George Braxton, Jr. and of Mary Carter, who died just seven days after giving birth. Carter’s father died when he was in his teens, and he was raised by family friends.

Carter Braxton was a descendant of some of the most distinguished families in Virginia in terms of wealth and influence. His grandfather, George Braxton, Sr., immigrated to Virginia from London about 1690 and lived in an estate called Mantua on the Mattaponi River. The Braxton family in England was of ancient origin and resided in Lancaster County. George Braxton married Elizabeth Paulin and, in his will of 1725, left a tract of 578 acres to his daughter. Elizabeth Paulin’s father, Thomas Paulin, was a justice of Old Rappahannock in 1688 and was one of the county officers in King and Queen County.

Carter Braxton’s father, George Braxton, Jr., received large land grants from King George II. He was a frequent member of the House of Burgesses from 1718 to 1734, and held lands in common with William Brooke, his son George Braxton, Humphrey Brooke, Sr. (his son in law) and Ambrose Madison (the grandfather of President James Madison).

Carter Braxton’s mother, Mary Carter, was the daughter of Robert “King” Carter and his second wife, Elizabeth Landon Willis. Robert was called “King” because of his great wealth and prominence. He was born at his father’s estate, Corotoman. He served in the House of Burgesses, where he was Speaker. He served as Treasurer of the Colony, member, and President of the King’s Council, and as Acting Governor for one year. His estate consisted of 300,000 acres of land and 1,000 slaves. Robert Carter built Christ Church in Lancaster County and served as vestryman of the church.

“King” Carter’s father (Carter Braxton’s great- grandfather) was Colonel John Carter of England. John Carter was the son of William Carter of Casstown, Hereford County, England and was born in 1620. The Colonel came to the Virginia colony in 1649 and built the ancestral home of Corotoman in Lancaster County. He served in the House of Burgesses, was an influential member of the King’s Council, and was a commander against the Rappahannock Indians in 1654. His descendants included three Signers of the Declaration of Independence: Carter Braxton, Benjamin Harrison, and Thomas Nelson.

Carter Braxton was educated at the College of William and Mary, and later became a member of its board of visitors. Shortly after graduating, his father died, leaving him the family estate of Newington.

In 1753, Braxton came into possession of the impressive manor house and plantation of Elsing Green. He sold Elsing Green in the early 1760’s but never lived there.

In 1755, Braxton married the wealthy, beautiful and amiable Judith Robinson, the daughter of Christopher and Judith Robinson of Hewick, Middlesex County, Virginia. Judith died shortly after the birth of their second child in 1757 leaving Braxton devastated with grief.

Following the death of his first wife, Braxton moved to England in 1757, where he remained for three years. During this time, he became familiar with the feelings and designs of the English government. His rank and fortune gave him access to the nobility from whom he obtained much valuable information: that Great Britain would support the exchequer by extracting money from the hardy pioneers of American in the form of new taxes. In 1760, Carter Braxton returned from Europe and was elected to the House of Burgesses where he became an active and prominent member. He was to continue in the House until 1775.

In 1761, he married Elizabeth Corbin, the daughter of Colonel Richard Corbin and Elizabeth Tayloe.

Elizabeth’s father, Colonel Corbin, was educated in England, and later served in the House of Burgesses, as President of the King’s Council, and receiver general of the colony for nearly 20 years. Elizabeth’s grandfather was Gawin Corbin who came to the Virginia colony in 1650. She was the great- granddaughter of the Honorable Henry Corbin of Hall End, Warwick County, England, who was born in 1594. His wife was a descendant of Sir Gilbert Grosvenor, who came to England with William the Conqueror in 1066.

In the 1760s, Braxton considered investing in the slave trade, exchanging letters with the Brown brothers in Providence, but the Browns proceeded on their own.

In the growing dispute with Great Britain Carter Braxton was loyal to Virginia, but held the more conservative views of the Tidewater leaders. He was present in the House of Burgesses when Patrick Henry’s resolutions condemned the Stamp Act.

In 1769, along with Washington, Jefferson, Patrick Henry, Peyton Randolph, and others he signed the Virginia Resolves, which declared that the House of Burgesses had the sole right to tax the inhabitants of the colony. Braxton also signed the Virginia Association, a non-importation agreement.

The day after the first hostilities at Lexington and Concord in 1775, Braxton became a member of the Virginia Colonial Convention. He then played a key role in the confrontation with Royal Governor Lord Dunmore.

Lord Dunmore confiscated the gunpowder stored in the Williamsburg magazine and placed it on a British warship. Militia units were eager to retaliate, but they were calmed by Peyton Randolph and George Washington. Patrick Henry, however, refused to be pacified, and led a militia unit into Williamsburg to demand the return of the gunpowder. Before hostilities broke out, Carter Braxton, speaking for Patrick Henry, convinced his father-in-law, Richard Corbin, who was receiver general of the Colony, to pay for the gunpowder, thus averting an open conflict.

When Peyton Randolph died suddenly in October, 1775, Carter Braxton was chosen to replace him in the Continental Congress.

Braxton was hesitant at first to support the growing sentiment for independence, and argued strongly against it. In April, 1776, he wrote, “Independence is in truth an elusive bait which men inconsiderably catch at, without knowing the hook to which it is affixed.”

Braxton pointed out that one republic after another had come to an unhappy ending. The Netherlands, he claimed, became “as unhappy and despotic as the one of which we complain,” and Venice “is now governed by one of the worst of despotisms.” He concluded that “the principle contended for is ideal, and a mere creature of a warm imagination.” The advantages of republics “existed only in theory and were never confirmed by the experience, even of those who recommend them.”

During the debate following Richard Henry Lee’s resolution for independence on June 7, Braxton continued to argue against separation. But by early July he had changed his mind, voting for independence on July 2, the Declaration on July 4, and signing the Declaration on August 2. At the first meeting that fall of the General Assembly of Virginia, Braxton and Jefferson received a vote of thanks ‘for the diligence, ability and integrity with which they executed the important trust repose(?d) in them as two of the delegates of the County in the General Congress.”

Braxton, however, was not reappointed to the Continental Congress, when he opposed a more democratic form of government desired by the delegates in the Virginia convention.

He was active and influential in the Virginia Legislature from 1777 to 1785, and from 1786 to 1797, he was elected, and re-elected, a member of the Council of State.

Braxton invested a great deal of his wealth in the American Revolution. He loaned money to the cause and funded shipping and privateering. Unfortunately, the British destroyed many of his ships, and ravaged several of his plantations and land holdings. He accumulated a great deal of debt and was forced to leave his estate at Chericoke in 1786 and move to a smaller residence in Richmond.

A fellow Signer of the Declaration, Dr. Benjamin Rush, described Carter Braxton as agreeable, a sensible speaker, and an accomplished gentleman, but someone strongly prejudiced against New Englanders. Others described him as a gentleman of cultivated mind and respectable talents. Although not possessed of the impressive eloquence of colleagues such as Patrick Henry, his oratory was described as easy and flowing. In his manners he was peculiarly agreeable and the language of his conversation was smooth. Despite his financial adversities and trying circumstances his reputation did not suffer. He maintained his well-earned fame as an able and faithful public servant, a worthy upright man. He was a faithful sentinel in the cause of freedom.

Biography credit here.

Final Thoughts

Carter Braxton’s journey from reluctant revolutionary to committed patriot exemplifies the complex path many colonists took toward independence. His initial opposition to separation from Britain stemmed not from loyalty to the Crown, but from a pragmatic assessment of history and the challenges facing republics. His eventual embrace of independence demonstrates the power of principle over prudence, as he chose to risk his vast fortune for a cause he had initially doubted. This transformation from skeptic to signer reveals the depth of conviction that ultimately united the diverse voices of the Continental Congress.

The magnitude of Braxton’s sacrifice cannot be overstated. As one of Virginia’s wealthiest planters, he had more to lose than most, yet he invested heavily in the revolutionary cause through loans, shipping ventures, and privateering operations. The destruction of his ships by British blockades and the ravaging of his plantations left him deeply in debt, forcing him to abandon his grand estate at Chericoke for modest quarters in Richmond. His willingness to risk—and ultimately lose—his fortune stands as a testament to the genuine commitment of the Founding generation, who pledged their “lives, fortunes, and sacred honor” with full knowledge of what those words meant.

Despite his financial ruin, Braxton maintained his dignity and continued his public service until his death in 1797. His colleagues remembered him as an accomplished gentleman and faithful public servant whose reputation remained unblemished even as his wealth disappeared. In many ways, Carter Braxton represents the unsung heroes of the Revolution—those who gave not their lives but their livelihoods, who sacrificed comfort and security for an uncertain future. His story reminds us that independence came at a tremendous personal cost to those who dared to sign their names to treason, and that the birth of American freedom was paid for not just in blood, but in the fortunes of men who chose country over comfort.

Thanks for reading!