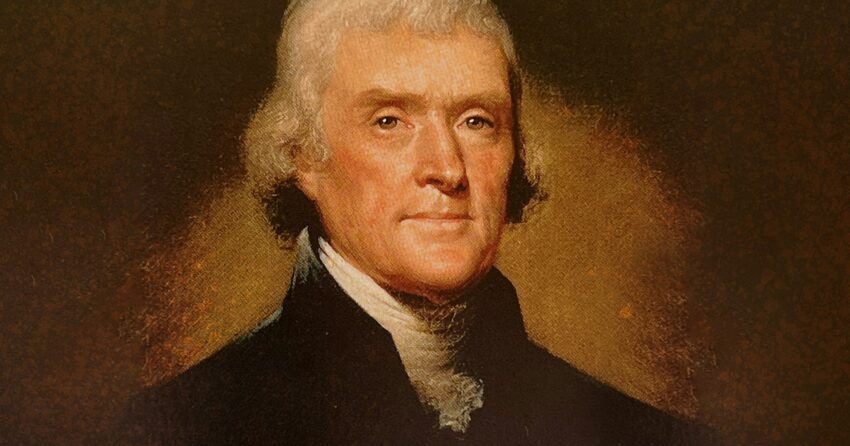

In the summer of 1776, Thomas Jefferson penned words that would have fundamentally altered American history—if only they had survived the editorial process. Among the 86 changes made to his original draft of the Declaration of Independence, none was more significant than the deletion of an entire paragraph condemning King George III for perpetuating the slave trade. This lost passage reveals both the moral contradictions at the heart of America’s founding and the political compromises that would haunt the nation for centuries.

The Deleted Words

Jefferson’s removed paragraph was a scathing 168-word indictment that would have been the longest grievance in the Declaration. He wrote:

“He has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating it’s most sacred rights of life & liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. This piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers, is the warfare of the CHRISTIAN king of Great Britain. Determined to keep open a market where MEN should be bought & sold, he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or to restrain this execrable commerce: and that this assemblage of horrors might want no fact of distinguished die, he is now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase that liberty of which he had deprived them, by murdering the people upon whom he also obtruded them; thus paying off former crimes committed against the liberties of one people, with crimes which he urges them to commit against the lives of another.”

The passion and moral clarity of Jefferson’s language stand in stark contrast to the measured tone of the Declaration’s other grievances. He called slavery a “cruel war against human nature itself” and labeled the slave trade “execrable commerce”—remarkably strong language from a man who himself owned six hundred enslaved people at Monticello.

The Red Pen Of The Committee Of Five

Between June 11 and June 28, 1776, Jefferson showed his draft to the Committee of Five—John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston. They made minor edits, but the major surgery came when the full Continental Congress debated the document from July 2-4. The Congress, as Jefferson later wrote in his autobiography, “mangled” his draft.

While he was angered by many changes, the removal of the slavery passage particularly stung. The deletion wasn’t subtle—the entire paragraph was struck, leaving no trace of Jefferson’s attempt to place blame for American slavery at the feet of the British Crown.

Why Was Jefferson’s Condemnation Of Slavery Removed?

The deletion of this paragraph highlights one of American history’s greatest ironies. Jefferson, who wrote that King George had waged “cruel war against human nature itself” through slavery, was simultaneously one of Virginia’s largest slaveholders. This man who penned the immortal words “all men are created equal” owned hundreds of human beings and, unlike some other founders, freed very few during his lifetime. Jefferson’s words against slavery—written by a slaveholder, removed by merchants and planters, and lost to history—embody the contradictions that would define America for generations.

English abolitionist Thomas Day captured this contradiction in a 1776 letter: “If there be an object truly ridiculous in nature, it is an American patriot, signing resolutions of independency with the one hand, and with the other brandishing a whip over his affrighted slaves.”

The lost paragraph of the Declaration of Independence stands as one of history’s great “what-ifs.” Its deletion reveals how the founders chose political expedience over moral clarity, unity over justice. That said, the reasons for removing Jefferson’s anti-slavery paragraph were both political and practical:

Southern Opposition

Jefferson later wrote that South Carolina and Georgia objected strongly to the passage. These states had “significant involvement in the slave trade” and their economies depended heavily on enslaved labor. As historian David K. Shipler notes, without the support of all thirteen colonies, independence would fail.

Northern Complicity

More revealing was Jefferson’s observation that Northern states also supported the removal, “for though their people had very few slaves themselves, yet they had been pretty considerable carriers of them to others.” New England merchants had grown wealthy from the triangular trade, transporting enslaved Africans across the Atlantic.

Political Unity

In July 1776, the paramount goal was colonial unity against Britain. The Congress chose independence over moral clarity, recognizing that condemning slavery could fracture the fragile coalition before it had even declared itself a nation.

Logical Inconsistency

There was also an inherent contradiction in blaming King George III for American slavery when colonists themselves had willingly participated in and profited from the institution for over 150 years.

The Impact

The moral clarity of Jefferson’s deleted passage was replaced with language that treated enslaved people as a threat rather than as victims of injustice. The final version of the Declaration, as historian John Ferling noted, became “the majestic document that inspired both contemporaries and posterity,” but it was a document that had compromised on the fundamental issue of human bondage.

As a result of the removal of Jefferson’s paragraph, America was born with what historian Joseph Ellis called a “silence” on its central moral contradiction. That silence would not be broken until it was shattered by civil war four score and seven years later.

Final Thoughts

Today, as we grapple with the legacies of slavery and systemic racism, the lost paragraph reminds us that the struggle between America’s highest ideals and its practical compromises began at the very moment of its birth. The words that were struck from our founding document on July 4, 1776, echo through history as both a road not taken and a reminder of the ongoing work required to form that “more perfect union.”

In the end, Jefferson was right about one thing: Congress had indeed “mangled” his draft. But perhaps the most profound mutilation was the removal of his tortured attempt to condemn the very institution from which he profited—a deletion that would ensure that the new nation would begin its life with the original sin of slavery embedded in its foundation, waiting for future generations to resolve the contradiction he could not.

Thanks for reading!