Today, let’s briefly review the following DAO voting systems: Conviction Voting, Futarchy, Holographic Consensus, Liquid Democracy, Multisig Voting, Permissioned Relative Majority, Token-based Quorum Voting, and Quadratic Voting.

Conviction Voting

Conviction voting is a mechanism used by DAOs to facilitate decision making and allocate resources based on the strength of individual preferences. DAO members are given a certain amount of voting power that increases over time based on their level of commitment and conviction to a particular proposal. Members can then use this power to vote on proposals and allocate resources according to their preferences. The key feature of conviction voting is individual accountability – members are incentivized to carefully consider the proposals and only vote for those they truly believe in, rather than simply casting a vote based on their personal biases or interests, because the more voting power a member puts behind a proposal, the more they stand to gain or lose if the proposal succeeds or fails.

Futarchy

In a Futarchy, a traditional democratic model is used to define what a DAO wants to achieve, but betting/prediction markets say how to get there. Said another way, elected representatives formally define and manage an after-the-fact measurement of community welfare, but market speculators decide on the policies that should be put in place to get the community to those chosen ends. The prediction markets of Futarchy solve informational inefficiencies often found in quadratic voting systems, while allowing a DAO to retain egalitarian properties. Further, by separating prediction from control, Futarchy reduces temptation to vote strategically based on herd dynamics rather than sincerely revealing one’s analysis, incentivizing DYOR and solving for the “Tragedy in Commons”.

Holographic Consensus

This model of voting aims to solve the governance scalability-resilience problem in decentralized organizations. Holographic consensus works by assigning “voice credits” to each DAO member based on their contribution to the DAO. These credits are then used to vote on proposals within the DAO. The holographic consensus mechanism also allows members to delegate their voice credits to others who they believe are better equipped to make informed decisions. This delegation can be temporary or permanent, allowing for fluid and dynamic decision-making within the DAO. In addition, holographic consensus voting systems typically allow for more than simple yes/no binary decision-making processes.

Liquid Democracy

Liquid democracy is a DAO voting system focused on vote delegation. In this case, a DAO assigns specialists to participate in an electorate that has the power to make decisions on behalf of DAO members. Members delegate their votes to trusted experts of their choice, who are better prepared to make the right decisions regarding the DAO’s future. This approach is more centralized than some other voting methods, but to counter that, DAO members have the power to transfer delegation at any time and assign new participants to the electorate.

Multisig Voting

Multisig voting is a DAO voting mechanism aimed at creating a balance between central authority and decentralization in an organization. Multisig voting requires that multiple parties (“signers”) approve or reject a proposal before it can be executed. Once the required number of signers have approved the proposal, the transaction is executed, and funds or assets are transferred as specified in the proposal. Multisig voting is often used in DAOs to ensure that no single member or group of members has total control over an organization’s treasury, mitigating the risks of abuse and fraud.

Permissioned Relative Majority

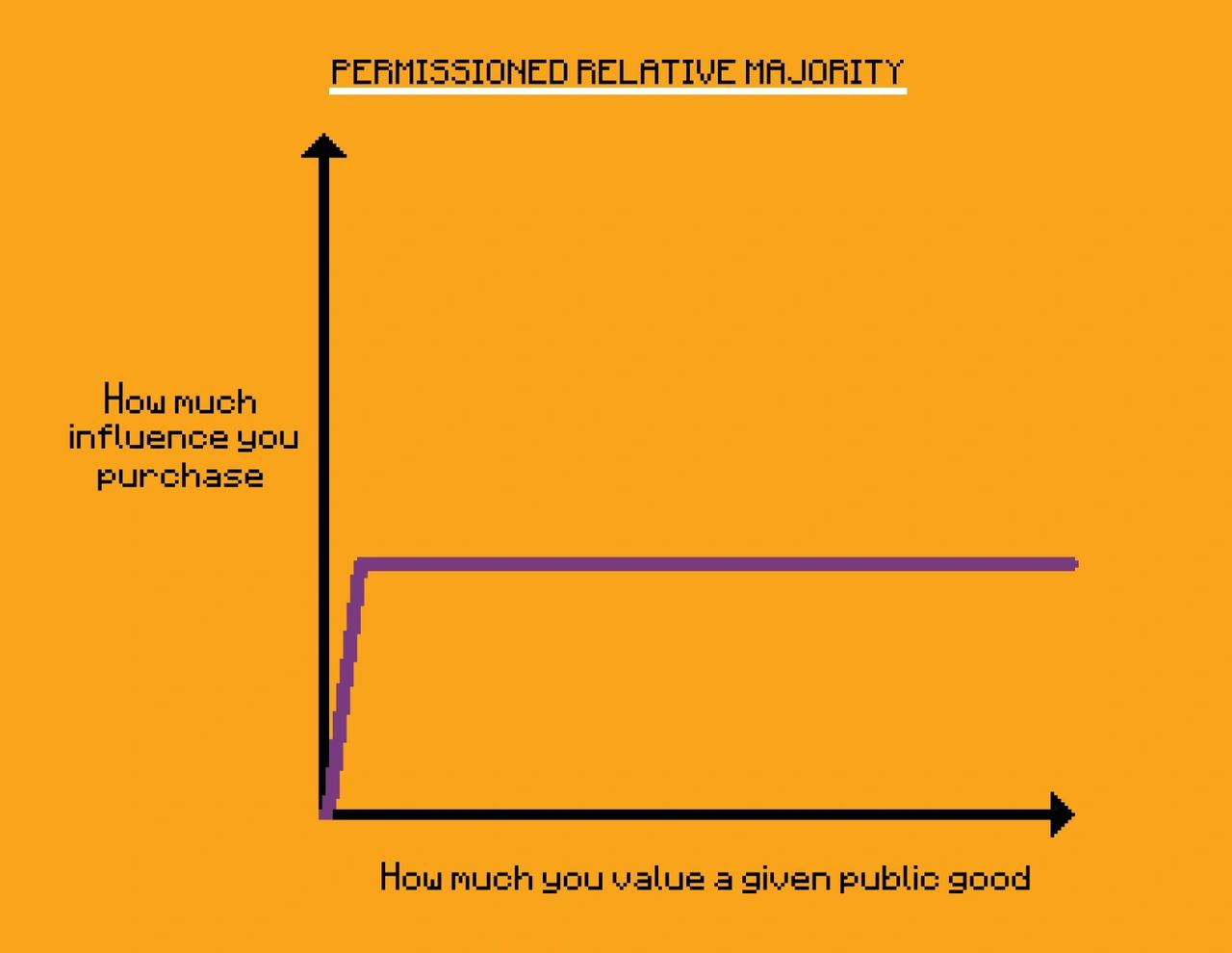

The permissioned relative majority is an easy to understand and straightforward voting system, making it convenient for participants. In this system of voting, there is no minimum voting requirement. Instead, the key factor is how many have voted “for” or “against” a proposal. Opponents of permissioned relative majority voting argue that this system can give too much power to small groups of members or even individual voters in gaining control over DAO funds. To overcome this challenge, it is suggested that proposals on which the DAO is to vote require sponsorship before coming to the community for consideration. In addition, a “rage quitting” mechanism can offer a solution to relative majority challenges. With the “rage quitting” voting mechanism, if a DAO majority approves a proposal, that proposal enters a grace period in which voters can reconsider and even withdraw their support from the vote. If the proposal no longer receives enough support after this stage, it is discarded.

Essentially a one-person-one-vote system of governance, the most pervasive of challenges with the permissioned relative majority is that it over-privileges the “little guy”, giving him the same voting power as the large player (whale). This conundrum is illustrated in the graph below.

Token-Based Quorum Voting

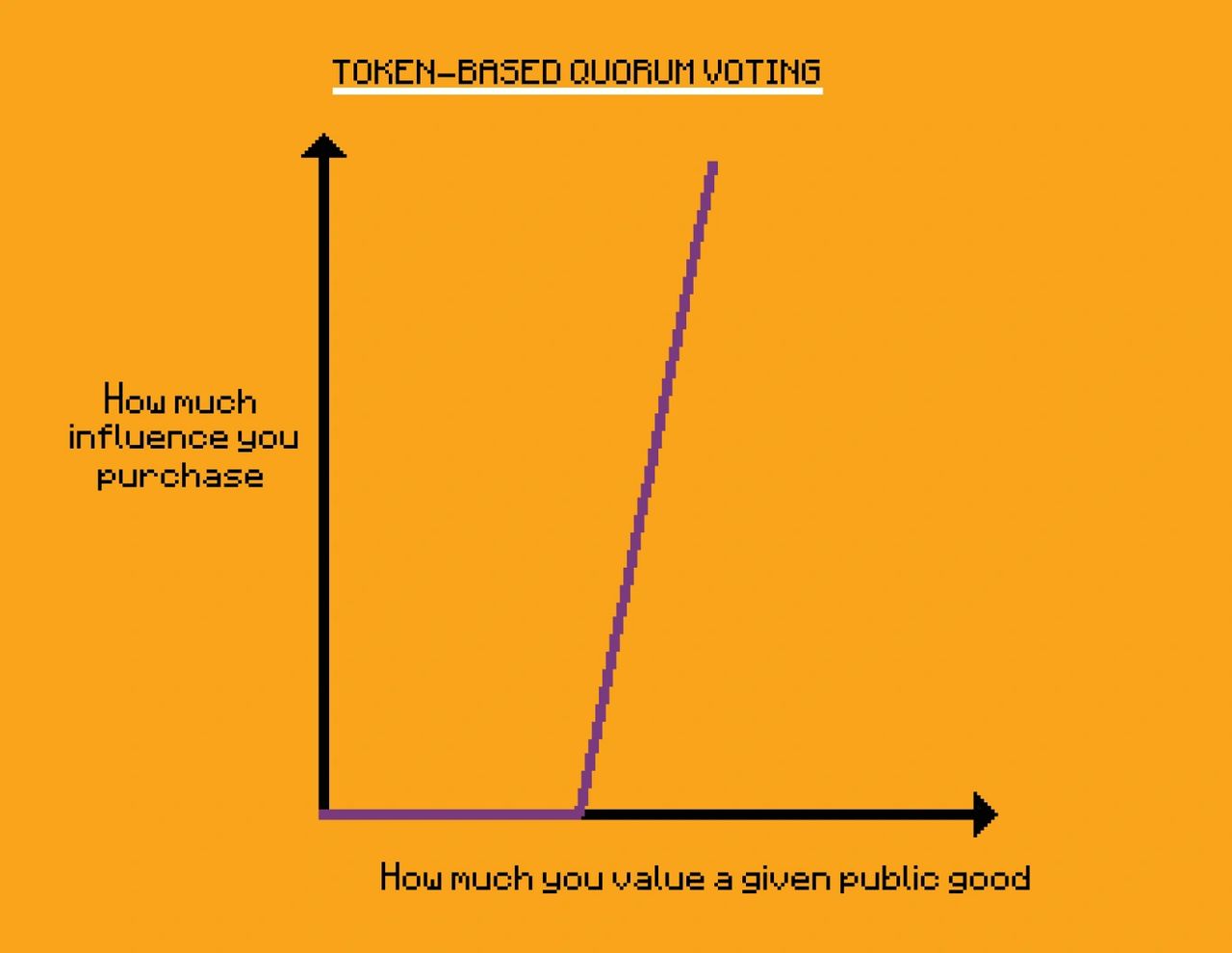

In this system, each member of the DAO is issued a certain number of tokens, which represent their ownership or stake in the organization. When a vote is called, each member can use their tokens to cast a vote. The total number of tokens used to vote is referred to as the “quorum.” In order for a decision to be made, a certain percentage of the total number of tokens in the organization must be used to cast votes. This percentage is known as the “quorum threshold” and is often set at 51%. If the number of tokens used to vote exceeds the quorum threshold, then the vote is considered valid and the decision is made based on the outcome of the vote. If the quorum threshold is not met, then the vote is considered invalid and the decision cannot be made.

A challenge to this system of voting is that it is often difficult to pinpoint an appropriate quorum for efficient and effective community voting. In addition, while token-based quorum voting is arguably the most common voting system used in decentralized communities, it is also a voting system prone to attack. With essentially a “one dollar, one vote” mechanism in play, big players (whales) have far too much power relative to the influence of smaller holders. The graph below shows how this voting system over-privileges members who are wealthy.

Quadratic Voting

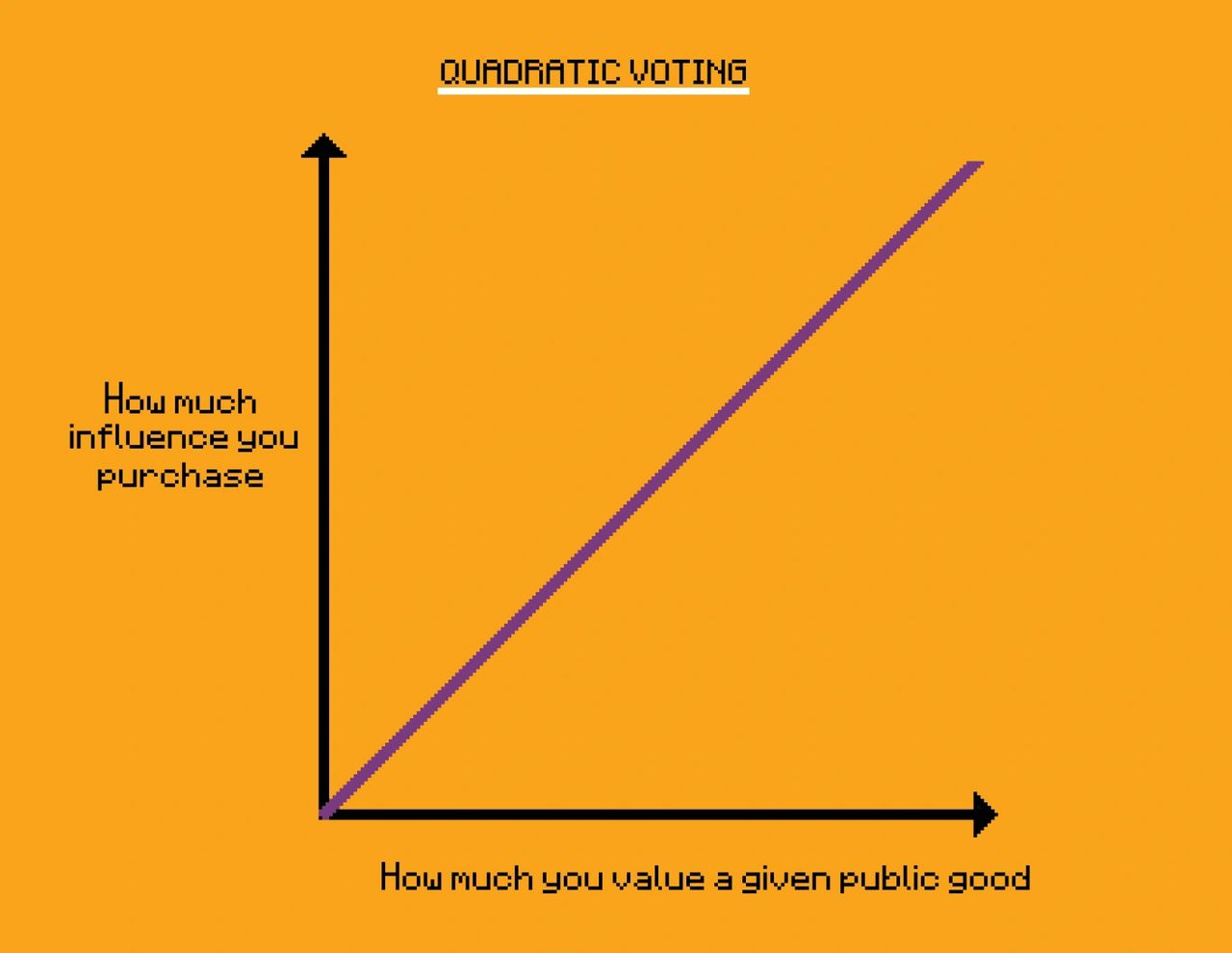

Quadratic voting is a voting system designed to give participants more influence over decisions in a democratic process by allowing them to express preferences in a nuanced way, promoting inclusivity. The basic idea is that each voter is given a certain number of tokens (or “voice credits”) that they can use to express their preference on a proposal. However, instead of each token counting as one vote, the number of votes a voter can cast is determined by the square root of the number of tokens they have. For example, if a voter has 100 tokens, they can cast 10 votes (the square root of 100). This has the effect of giving more weight to those who are more passionate about a proposal, while limiting the influence of those who may hold a large number of tokens, but don’t necessarily have a strong preference one way or another.

In effect, how much influence one “buys” is proportional to how much one cares. This n’th unit of influence costs $n, expressed in the graph below.

Quadratic voting systems are appropriate in governing resources that affect large numbers of people, are optimal in cases when a DAO is in need of making a fixed number of collective decisions, and are ideal in contexts with more than two choices. However, opponents (who typically favor Futarchy governance models) point to two areas of concern for quadratic voting methods. First, there is the problem of information asymmetry and/or low quality of information. Second, there is a risk of malicious actors taking control of ballot proposal processes.

Comparison Of Systems

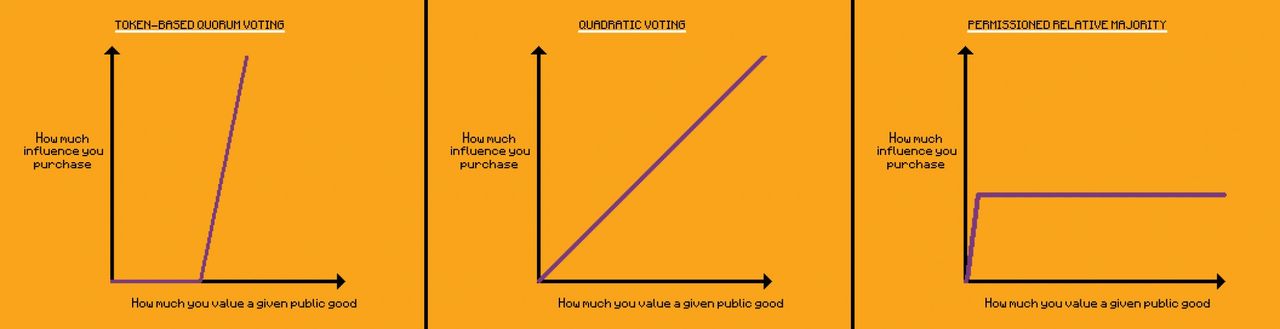

As compared to token-based quorum voting (which over-privileges concentrated interests) and systems that use a permissioned relative majority (which over-privileges diffuse interests), only quadratic voting balances one’s voting and purchasing power against one’s desire for an outcome. See below for a comparison graph of these three voting systems.

Final Thoughts

The evolution of DAO voting systems represents one of the most fascinating experiments in digital democracy. Each system we’ve explored—from Conviction Voting to Quadratic Voting—attempts to solve fundamental challenges in collective decision-making: How do we balance the interests of large and small stakeholders? How do we incentivize informed participation? How do we prevent governance capture while maintaining efficiency?

What’s clear is that there’s no one-size-fits-all solution. The optimal voting system depends heavily on the DAO’s specific goals, community composition, and the types of decisions being made. A small, mission-driven DAO might thrive with Multisig Voting, while a large protocol DAO might benefit from the nuanced expression enabled by Quadratic Voting or the market-driven insights of Futarchy.

As the DAO ecosystem matures, we’re likely to see hybrid approaches that combine elements from multiple systems. Perhaps most importantly, these experiments in decentralized governance are generating valuable insights that extend beyond blockchain—offering new perspectives on how we might reimagine democratic processes in the digital age.

The journey toward truly effective decentralized governance is still in its early stages, but the innovation happening in this space gives reason for optimism. As DAOs continue to iterate and evolve their voting mechanisms, we move closer to realizing the vision of organizations that are both genuinely democratic and practically effective.

Thanks for reading!