Cults and true believers have always been cheap to create. But, in the world of Web3 and an attention economy, these groups aren’t just cheap to create, they also provide means for asymmetrical returns on cost, effort, time, and more. For better or worse, the rulebook for creating cults and true believers is well-established and easy to understand – both cults and believers all “look” the same and persist because of hope on one hand, and frustration on the other.

As said by Robert Finkelstein: “Equality without freedom creates a more stable social pattern than freedom without equality. A rising mass movement attracts and holds a following not by its doctrine and promises, but by the refuge it offers from the anxieties, barrenness, and meaninglessness of an individual existence.”

What Is Meant By “Cult”? A Pattern Of Social Relations

“Cult” is not a label to be applied to a group we don’t like or that has “weird” habits. Rather, the word “cult” describes a pattern of social relations within a group. At the core of these relations is dependency.

In a cult, members are dependent on the group and its leaders for most, if not all, resources, including money, food and clothing, information, decision making, and perhaps, most importantly, self-esteem and social identity.

This member dependency results in a specific pattern of relations:

- Communication is highly centralized, with little information available from outside the group.

- The agenda, objectives, and work tasks are set by the elite.

- Given the importance of the group to the individual, all influence and persuasion is directed toward maintaining the group.

- Persuasion is based on simple images and plays on emotions and prejudices.

All Cults Are Taxonomically Equivalent

While the success of a mass movement is typically ascribed to its faith, doctrine, propaganda, leadership, or ruthlessness, a cult’s vigor – in all cases – actually stems from the propensity of its followers for united action and self-sacrifice, and all true-believer mass movements, or “cults”, are taxonomically equivalent. As such, when people are ripe for a mass movement and cult engagement, they are usually ripe for any effective movement, not solely for one with a particular doctrine or program.

Since all cults draw their adherents from the same types of humanity and appeal to the same types of mind, it follows:

- All cults are competitive, and the gain of one in adherents is a loss of all the others.

- All cults are interchangeable and transformable.

- It is rare for a cult to be wholly of one character; it usually displays some facets of other types of movement, and sometimes it is two or three movements in one (such as religious, social, and nationalistic).

- The problem of stopping a cult is often a matter of substituting one movement for another (for example, a religious revolution can be stopped by promoting a social or nationalistic movement).

What Are The Characteristics Of A Cult?

Cults typically share several key characteristics that distinguish them from mainstream religious or social groups. Not all cults exhibit every characteristic, and these traits exist on a spectrum. The key factor is the degree of manipulation and control exerted over members’ lives and thinking.

Leadership and Authority

- Authoritarian leadership with a charismatic figure who claims special knowledge, divine connection, or unique insight

- The leader’s word is absolute and questioning is discouraged or punished

- Often includes a hierarchy where proximity to the leader determines status

Control Mechanisms

- Isolation from family, friends, and outside influences

- Control over information – limiting access to external media or alternative viewpoints

- Financial exploitation – members required to donate money, property, or work for free

- Regulation of daily activities including diet, sleep, dress, and relationships

Belief System

- Claims to exclusive truth – only the group has the correct path or knowledge

- Black-and-white thinking that divides the world into “us vs. them”

- Persecution complex – outside criticism is proof the group is right

- Moving goalposts – failed predictions or promises are reinterpreted rather than acknowledged

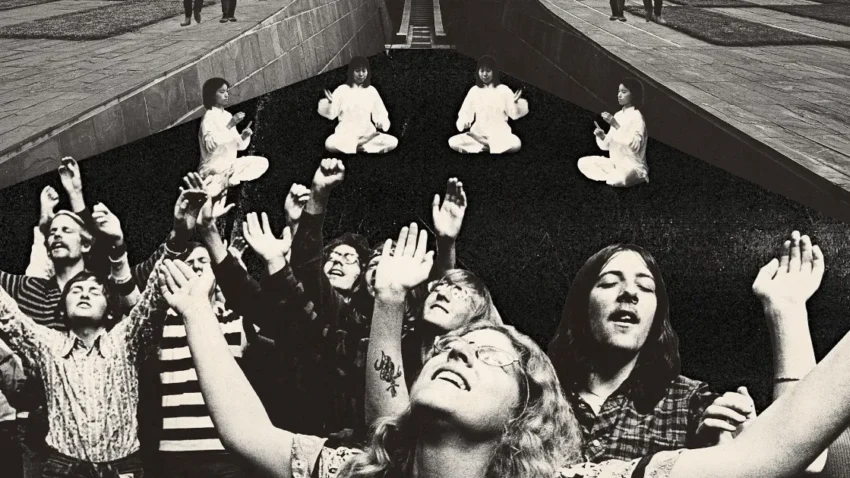

Psychological Manipulation

- Love bombing – overwhelming new members with attention and affection

- Thought-stopping techniques like repetitive chanting or meditation to prevent critical thinking

- Confession sessions where personal information is gathered and potentially used for control

- Gaslighting members about their own perceptions and memories

Consequences for Leaving

- Threats of spiritual damnation, physical harm, or personal ruin

- Shunning by other members, including family

- Difficulty readjusting to outside life due to dependency fostered by the group

Final Thoughts

The most unsettling truth about cults isn’t their strange beliefs or charismatic leaders—it’s how ordinary the path to membership can be. In an era of algorithmic echo chambers and parasocial relationships, we’re all navigating spaces designed to cultivate dependency. The difference between a community and a cult often comes down to a single question: Can you leave without losing yourself?

Understanding cults as patterns of dependency rather than just “weird groups” reveals why they persist across every era and culture. They don’t prey on the weak or foolish; they exploit universal human needs for belonging, meaning, and identity. In our hyperconnected yet increasingly isolated world, these vulnerabilities have only intensified.

The Web3 landscape, with its promises of revolution and riches, has become particularly fertile ground for cult-like dynamics. When financial incentives merge with ideological fervor and technological complexity that few truly understand, the conditions are perfect for fostering the kind of dependency that defines cultic relationships.

Perhaps the best defense against cultic thinking isn’t skepticism of others, but honest examination of our own dependencies. What beliefs do we hold that we’re afraid to question? Which communities would we struggle to leave? Where have we traded critical thinking for comfortable certainty?

In recognizing that all cults are “taxonomically equivalent”—drawing from the same human needs and following the same patterns—we gain a powerful lens for understanding not just fringe movements, but the mechanics of belief itself. The antidote to cultism isn’t cynicism; it’s cultivating genuine interdependence rather than dependency, maintaining multiple sources of meaning and community, and preserving the freedom to doubt, question, and ultimately, to leave.

The cult’s promise is simple: surrender your autonomy, receive certainty. But real community—messy, challenging, and genuinely transformative—requires something far more difficult: showing up as a whole person, capable of both belonging and walking away.

Thanks for reading!