The term “Asymmetrical Warfare” is frequently used to describe what is also called “guerrilla warfare”, “insurgency”, “terrorism”, “counterinsurgency”, and “counterterrorism”, essentially violent conflict between a formal military and an informal, less equipped and supported, undermanned but resilient opponent. Asymmetric warfare is a form of irregular warfare. Many have tried to describe this new type of warfare, and many catchphrases and buzzwords have come and gone: low-intensity conflict, military operations other than war, asymmetric warfare, fourth-generation warfare, irregular warfare.

What’s The Problem?

In any event, while warfare today has taken on a new form and grown to new level, this type of warfare is not new, as are few of the tactics. The concept of asymmetrical warfare has been around for centuries. Following the teachings of Sun Tzu, all warfare is asymmetric because one exploits an enemy’s strengths while attacking his weaknesses. The Greeks used the Phalanx to defeat a mounted enemy. Hannibal used a feint in the middle of his forces with a double-envelopment to achieve victory over the Romans. Every time a new tactic or invention changed the fortunes and power of one army or empire over another, an imbalance or asymmetry occurred the weighting to one side created the conditions for victory.

What is new is that this type of war has reached a global level, and the United States and its allies have found themselves ill prepared.

“This is another type of war, new in its intensity, ancient in its origin – war by guerrillas, subversives, insurgents, assassins, war by ambush instead of by combat; by infiltration, instead of aggression, seeking victory by eroding and exhausting the enemy instead of engaging him. . . . It preys on economic unrest and ethnic conflicts. It requires in those situations where we must counter it, and these are the kinds of challenges that will be before us in the next decade if freedom is to be saved, a whole new kind of strategy, a wholly different kind of force, and therefore a new and wholly different kind of military training.” – President John F. Kennedy, addressing graduating West Point class of 1962

The Four Elements Of Asymmetrical Warfare

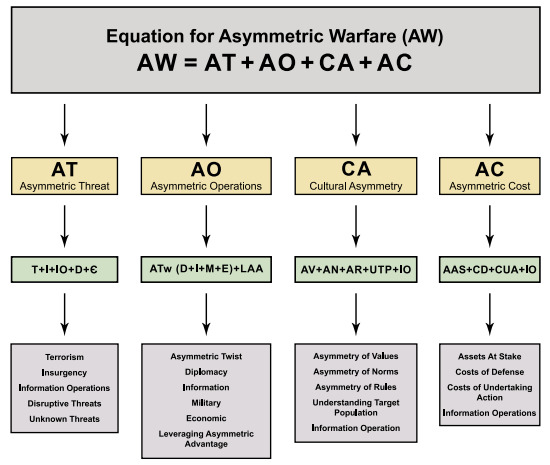

Asymmetrical Warfare follows a “simple” equation that includes Asymmetric Threat, Asymmetric Operations, Cultural Asymmetry, and Asymmetric Cost.

1. Asymmetric Threat

Terrorism: Terrorism includes all of the known forms of terrorism that exist today: suicide terrorism, catastrophic attacks such as the strikes on 9/11, political assassination, biological strikes like anthrax mailings, and many others. Terrorism is meant to produce a horrific effect. In the Information Age, terrorism is much more effective because a terrorist’s message is disseminated and its impact is felt instantly and worldwide. Threat and message mean more to a terrorist than the action itself; success is measured by the disruptive and psychological effect of an action, not by the body count. Terrorist networks can operate with a very decentralized command structure. Terrorists do attempt to achieve political goals, as per Clausewitz’s definition of warfare in general; however, the support of a population is not essential to a terrorist.

Insurgency: At its root, an insurgency is a revolutionary war. Asymmetries abound in an insurgency. The key is that, unlike a terrorist, an insurgent is completely reliant upon the population, and the population is the objective for both the insurgent and the counterinsurgent. Kilcullen mentioned that one key difference between the insurgency in Iraq and past examples of insurgency is that the Iraqi insurgency was decentralized. In Vietnam, for instance, all of the direction of the insurgency came from Ho Chi Minh. In Iraq, however, there were at least 17 insurgent organizations and four terrorist organizations that the United States identified, many of them at odds with one another as well as with the counterinsurgent forces. Also, Landry pointed out that many of al Qaeda’s actions and strategies more closely resemble those of a global transnational insurgent than of a terrorist. Much more like a revolutionary than a terrorist, Osama bin Laden conducted his actions to attempt to gain the support of a populace.

Information operations: Galula stated in Counterinsurgency Warfare that information operations (IO) are key. An insurgent’s greatest asset is an idea; he wants to spread this idea and convert it into more tangible assets like soldiers and support. The enemy wages information warfare by issuing propaganda, creating lies and developing conspiracies. The enemy, like the insurgents described by Galula, can bank currency on mere promises, rather than upon action. They can also seek to drive a wedge between the target population and a target superpower, such as the United States. This was clearly exemplified by the violence that followed the publication of the Danish cartoon depicting the Prophet Mohammed.

Disruptive threats: Promoting disorder is a legitimate objective for the asymmetric enemy. Between terrorism and disruptive threats lies much overlap. When conducting a disruptive strike, an asymmetric enemy need not even commit an action; the mere threat of action is enough to disrupt way of life. This holds true in the United States, but even more so in parts of the world where suicide bombing is part of daily life. The impact of a disruptive strike is measured in psychological rather than physical effect. Disruptive threats weigh greatly in asymmetric cost, as will be discussed later. A strategist combating disruptive threats must consider that until the average American truly understands the nature of asymmetric warfare, great measures at a great cost must be taken to make people feel safe. A strong case in point is the 9/11 terrorist strikes: Billions of dollars were lost in impeded air travel shortly after 9/11, and billions more have been spent to ensure that 9/11 could not happen again, rather than spending this money and intellectual energy to find and fix the next U.S. weakness.

Unknown threats: In the equation of asymmetric threat, there is the vast and ambiguous unknown term denoted by a symbol. An asymmetric enemy could use virtually any means to achieve his goal. However, it is important to clearly delineate the difference between a true asymmetric enemy and that enemy’s tools. Many people view crime, organized crime, hate crime, disease, drug trade, protests, natural disaster, peaceful civil disobedience or human trafficking as potential asymmetric threats. These in and of themselves are not the enemy because they fail to meet the Clausewitzian principle of politics through other means. Rather, they are events that are profit-motivated, directed toward minorities rather than toward the government, part of nature or part of the political life of a free democracy. However, each of these could be used by an asymmetric enemy to achieve his goals. In this case it becomes a tool and DOES fall under the realm of asymmetric threat. Criminal elements can supply and assist enemies, protestors can further an enemy’s cause, natural disasters can provide a disruption that an enemy can capitalize upon; however, none of these is motivated by the ideology of the enemy. A criminal seeks profit and avoids arrest; his ideology is moot. Criminals can be bribed to work against the enemy, or intimidated into submission if their price is too high. Each enemy tool must be addressed by a strategist, as long as that tool is not targeted as the actual enemy. Targeting these forces as an enemy instead of as a tool can cause the population – the true objective – to become more sympathetic to the enemy’s ideology.

2. Asymmetric Operations

Asymmetric twist: Asymmetric operations are those operations that are planned and conducted by the stronger side of an asymmetric war. They can be thought of as offensive operations. They consist primarily of putting an asymmetric twist on the traditional spheres of national power, such as diplomacy, information, military and economic (DIME). In addition to placing an asymmetric twist on DIME, one also must look to leverage asymmetric advantage wherever possible.

Diplomacy: As Galula pointed out that politics has primacy in an insurgency, and Clausewitz pointed out that all wartime objectives are political, diplomacy has primacy in asymmetric war. This is sometimes easy to forget since most asymmetric enemies are non-state actors. However, if counterinsurgency principles are applied to asymmetric warfare on the global-transnational scale, the population is still the objective. The State Department’s mission is diplomacy; thus far they have focused only on nation-states and international organizations. They should be organized and equipped to engage a target population through diplomatic efforts either directly or by working through the legitimate governments of the nation states.

Information: There are four very important concepts about information warfare that anyone conducting an asymmetric war must understand. The first concept is that information warfare in the Information Age is not waged just by very specialized military units on the ground. Psychological operations (PSYOP) products are targeted communications aimed at a specific group or demographic and delivered on a schedule as part of a larger plan. In contrast, information operations are conducted every time an official of the United States (or the West), whether elected, appointed or uniformed, makes any public statement; regardless of the intended target, the message is immediately disseminated worldwide. The second concept is that actions, or lack thereof, speak much louder than words. As Galula stated: “With no positive policy but with good propaganda, the [asymmetric enemy] may still win. . . . [We] can seldom cover bad or nonexistent policy with propaganda.” The third concept is that the IO message comes across much more convincingly when it is delivered by a local leader rather than by a Western spokesman. Whenever possible, the United States should engage friendly sheikhs, imams, elders and elected officials to disseminate IO themes. The last great concept to take away is that, unlike traditional warfare wherein any action by the friendly side is seen as progress, an action by the U.S. side in an information war can just as easily impede progress or take giant leaps backward if the consequences are not thoroughly and carefully considered. The lead agency in information warfare should be the State Department. However, coordination must occur at all levels, and good policy, supported by organization, knowledge and leadership, is the most important aspect in winning.

Military: Asymmetric military operations mainly comprise direct action (anti-terrorism), unconventional warfare (counterinsurgency), psychological operations, civil-military operations, foreign internal defense and special reconnaissance. Ironically, until recently U.S. Army Special Operations Command trained for and specialized in each of these types of operations, leaving the rest of the Army to focus on traditional missions. Today, however, given the nature of the asymmetric war the United States is fighting, the rest of the military is quickly learning to perform of these operations. Counterinsurgency has come to the forefront of military thinking due to the global situation today. The U.S. military is making huge strides in the realm of counterinsurgency; however, the State Department – among other federal departments – is only just beginning to realize its own vastly important role in winning a counterinsurgent war. Once again, as Clausewitz stated, “warfare is simply politics through other means.”

Economic: The most visual asymmetric economic operation is development and reconstruction. Foreign aid, trade policy and foreign direct investment (FDI) also play vital roles in waging asymmetric economic operations. In a war where the population is the objective, that target population must be able to see and understand the tangible benefit for supporting the side with the asymmetric advantage and to see and understand a material disadvantage for supporting the asymmetric enemy. Stick-and-carrot techniques are important, as is coordination at all levels. All aspects of economic operations must be coordinated and nested with the diplomatic, information operations and military campaigns.

Leveraging asymmetric advantage: Finally, the side of an asymmetric war that wields the asymmetric advantage must understand how to leverage that advantage against the enemy. Asymmetric advantage comes primarily in the following forms: technology, intelligence, communications, conventional military forces and economic resources. Although much of asymmetry highlights the advantages possessed by the weaker side, the United States must recognize and appreciate its own vast advantages and use them against the enemy.

3. Cultural Asymmetry

Cultural asymmetry is one of the hardest concepts to grasp, but it is one of the most crucial in an asymmetric war. Since asymmetric warfare is population-centric, understanding the population – the center of gravity – cultural asymmetry feeds into all other operations. Understanding of cultural asymmetry also helps identify and prepare for asymmetric threats because analysts should have a better understanding of the enemy’s capabilities and motives. Cultural asymmetry is not new to American forces. During the development and reconstruction phase following World War II, when the allies were rebuilding Japan, General Douglas MacArthur exhibited a keen grasp of cultural asymmetry when he allowed Japan to keep its emperor rather than punishing him as a war criminal, even though the concept of an emperor ran counter to American values.

Asymmetry of values: Bismarck’s statement that the strong is weak because of his moral scruples and the weak grows strong because of his audacity referred to cultural asymmetry of values, norms and rules. The West believes that it values life too greatly to employ suicide as a political or military tactic. Suicide terrorists see themselves as sacrificing their lives to achieve legitimate military goals – and, in the context of the terrorist suicides of Islamic extremists, to reap commensurate rewards in heaven. This is foreign to the Western mindset; without condoning such actions, we must look through our cultural barriers to try to understand why someone would commit such an act. Understanding values is crucial in a population-centric asymmetric war. Simply put, the enemy’s greatest asset is an idea.

Asymmetry of norms: The West has gone to great lengths to legitimize acts of warfare by identifying combatants and noncombatants. However, if a non-Western culture vilifies an entire group of people for committing economic and political as well as military atrocities, then they can view the people working in the World Trade Center on September 11th, 2001 as combatants, whereas the West justifiably identifies them as innocent noncombatants. Once again, the West need not accept the enemy’s norms; strategists must simply attempt to understand them so strategy can be focused accordingly. Also, in the Muslim culture loyalty is placed above honesty when weighing one’s honor. Many U.S. Soldiers and commanders complain when a member of the local population lies to protect the insurgents/terrorists/cache, etc. Although Soldiers take this as a strong affront, and their norms cause them to feel that this man has no honor or integrity, they must understand that if someone appealed to his loyalty – whether to culture, religion, nationality or tribe – whether or not he likes that person or supports his cause, the man is honor-bound to lie for that person. The man’s honor is defined more greatly by his loyalty than by his honesty.

Asymmetry of rules: Asymmetric enemies are bound by neither the laws of land warfare nor the Geneva Conventions. They routinely direct violent action against civilians. They use tactics of terror and horrific images. Many terrorists and insurgents are also willing to sacrifice their own lives for their cause in a suicide strike. All of these must be weighed when planning to fight an asymmetric enemy. No atrocity is beyond this enemy’s capability

Understanding target population: When waging a population-centric war, strategists must identify the values and norms of the target population. These may be very different from those of the enemy and, if so, must be exploited. If the target population’s values and norms are very different from those of the West, then every effort must be made to understand this and to be aware.

Information operations: Cultural asymmetry is crucial in waging information warfare. As previously stated, information warfare is waged whenever any Western spokesperson makes a public statement and any time the West acts or fails to act in a given situation. Often, Western leaders make statements for their own benefit and without consideration of their impact on target populations.

4. Asymmetric Cost

Galula noted in 1964 the asymmetry of cost between an insurgent and a counterinsurgent. An insurgent blows up a bridge – a counterinsurgent now must guard all bridges. An insurgent throws a grenade into a theater – a counterinsurgent must take very expensive steps to ensure that the population feels safe. This concept is drastically illustrated today in the tremendous cost to the United States to secure its airways after the relatively inexpensive (for the attackers) 9/11 attacks. Asymmetry of cost is further illustrated in the cost of waging warfare in general with a non-state terrorist organization. When a nation-state wages war against a peer nation, each member of the conflict has similar risks at stake: population, land and interests to defend. When a non-state actor like a terrorist organization wages war against a nationstate, the non-state actor has no population or land at risk and therefore bears a lower cost in waging warfare.

“Disorder is cheap to create and very costly to prevent. Because we cannot escape the responsibility of maintaining order, the ratio of expenses between us and the asymmetric enemy are high. Because of the disparity in cost and effort, the asymmetric enemy can thus accept a protracted war; we should not. The asymmetric enemy is fluid because he has neither responsibility nor concrete assets; we are rigid because we have both.” – Galula

Assets at stake: A nation state that goes to war places many assets at risk: population, land and interests. A non-state actor’s or an insurgent’s only asset is his idea; he has no land or population. He may have interests, and he probably has a target population. The goal of the players on both sides of an asymmetric war, as in a counterinsurgency, is to win over the population to support their side – only then can the enemy grow weak. If an asymmetric enemy has interests, then these interests should be targeted as well. When fighting other than a nation-state, however, one must recognize the assets at stake for each side of the asymmetric war

Costs of defense: As Galula noted, “Disorder is cheap to create and very costly to prevent”. It is cheap for an insurgent to bomb a bridge, but expensive for a counterinsurgent to guard all of the bridges. We have seen that it is cheap for al Qaeda to hijack airplanes but expensive for the United States to maintain air security. It is cheap to mail anthrax but expensive to screen the mail.

Costs of undertaking action: Also, as Galula states, to be effective, a counterinsurgent’s forces must be ten or twenty times the size of the insurgent’s. This lends itself to the asymmetric cost of the defense. An insurgent can afford to wait, and he chooses where to strike. The drawn-out nature of a counterinsurgency makes it extremely costly. However, as stated under Information Operations, failure to act in a given situation loses more of the population to the insurgency. This same principle can be true on the strategic level. Demonstrating to the world that the United States and its allies are willing to help in the aftermath of a natural disaster such as the December 2004 tsunami that struck Indonesia or the October 2005 earthquake in Pakistan gained tremendous ground in this asymmetric war.

Information operations: Information operations holds a position under Asymmetric Cost due to the costs associated with conducting information operations in an asymmetric war. The enemy can base his entire IO campaign on rumor, propaganda and conspiracy theories. The West can base theirs only on concrete actions – and they are judged very harshly when they fail to act. It is hard for someone to grasp the concept that the United States can place a man on the moon but cannot turn on a village’s electricity. Due to this asymmetry of cost in the realm of information operations, the West might lose ground every day without ever being aware, simply because the enemy’s propaganda mechanism leads the populace to believe, for example, that Allah is punishing them with a lack of rain for their cooperation with the infidels.

Final Thoughts

Asymmetrical warfare represents one of the most complex challenges facing modern military and diplomatic establishments. As this analysis demonstrates, success in such conflicts requires a fundamental shift in thinking—from focusing on military superiority to understanding that the population is the true center of gravity. The four elements of asymmetrical warfare—threat, operations, cultural asymmetry, and cost—are deeply interconnected, and failure to address any one element can undermine efforts in the others.

Perhaps the most critical lesson is that traditional metrics of military success often prove misleading in asymmetric conflicts. Body counts, territory controlled, and enemy assets destroyed matter far less than the perceptions and allegiances of the local population. A single misguided action that alienates civilians can undo months of careful relationship building, while a well-timed humanitarian response can shift public opinion more effectively than any military operation.

The cost imbalance inherent in asymmetrical warfare poses a particular challenge for democratic societies. As Galula noted, disorder is cheap to create but expensive to prevent. This reality demands that strategists think creatively about resource allocation and develop sustainable approaches that don’t exhaust national will or treasury. The solution often lies not in matching the enemy’s tactics but in leveraging asymmetric advantages—technology, economic resources, diplomatic networks—in ways that resonate with local populations.

The ultimate paradox of asymmetrical warfare is that true victory often looks nothing like traditional military triumph. It manifests instead in the gradual strengthening of legitimate governance and the patient cultivation of cross-cultural understanding.

Thanks for reading!