T.L.D.R. –

- Age at Signing: 46

- Occupation: Merchant

- Key Perspective/Position: Conservative but supportive

- Personal Sacrifice: Never married after fiancée died

- Unique Contribution: Helped establish Navy

Introduction

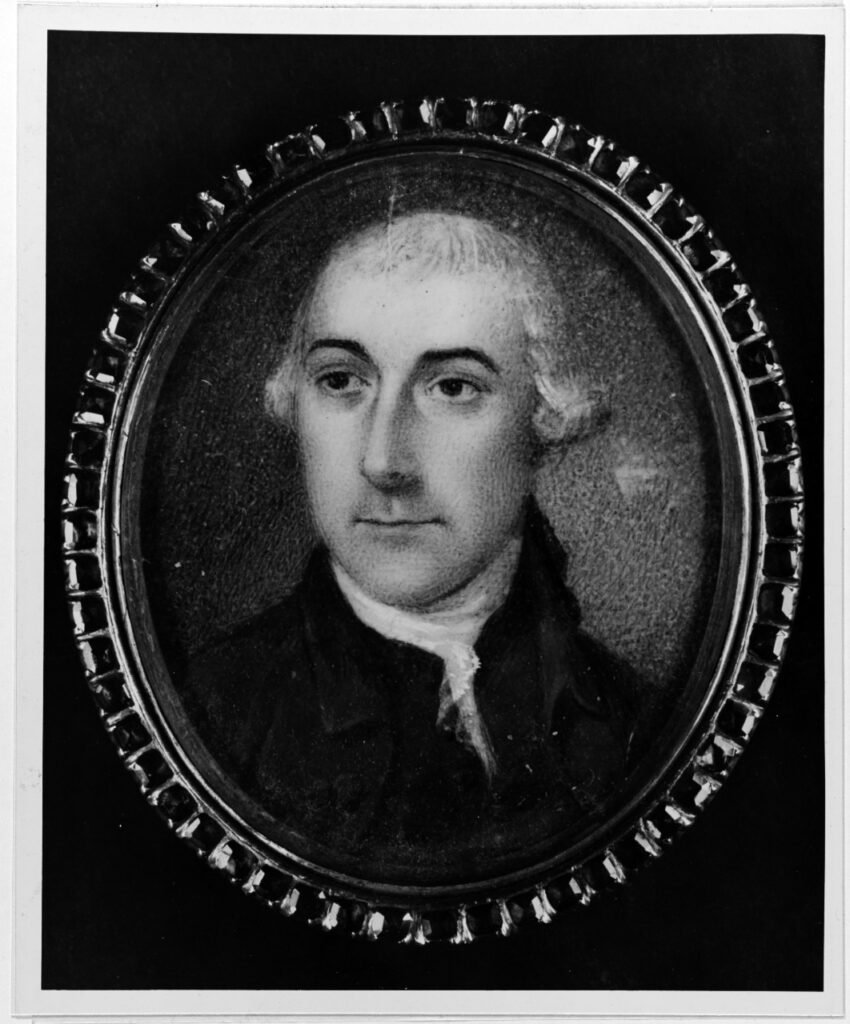

Joseph Hewes was born on January 23, 1730, near Princeton, New Jersey, into a Quaker family. He received a strict religious upbringing and standard education. Around 1750, he moved to Philadelphia to apprentice with merchant Joseph Ogden. In 1760, Hewes relocated to North Carolina, building prosperous mercantile businesses. After partnering with Robert Smith, he expanded his enterprise, buying a wharf with a small fleet. He became engaged but his fiancée died before their wedding, and he remained a bachelor.

Three years after arriving in Edenton, the community elected Hewes to the North Carolina Assembly, where he served from 1766-1775. He helped prepare the “Halifax Resolves” and presented them to Congress. He also helped draft the “Olive Branch Petition,” outlining grievances against Britain. King George rejected it immediately.

In 1775, North Carolina elected Hewes to the Second Continental Congress. He served on the committee of claims, helped lay the Navy’s foundations with John Adams, and sat on the committee preparing the Articles of Confederation. He died on November 10, 1779, after a long illness, at age 49.

Contribution to Independence: As one of the most conservative signers, Hewes’s support for independence showed even cautious merchants recognized the necessity of separation. His work establishing the Continental Navy proved vital to the war effort.

A Brief Biography

As a signer of the Declaration of Independence Joseph Hewes, with more than twenty years’ experience as a sailing merchant dealing with Britain, made some outstanding contributions to the founding of the Nation. This has been somewhat ignored in history because he had no direct line descendants.

Joseph Hewes was born January 23, 1730 at Maybury Hill, an estate on the outskirts of Princeton, New Jersey. He was the son of Aaron Hewes and Providence Worth. His parents were Quaker by faith and successful farmers in one of the Settlements of the Connecticut Colony. The original Hewes line emigrated to Pennsylvania from England, about 1635.

Aaron and Providence were married in Connecticut in 1728. Indian massacres and the religious intolerance of Quakers remaining among the Puritans of New England forced them to move to New Jersey to find a more peaceful and secure environment. They settled in an estate named “Maybury Hill” and occupied it from 1730 to 1755. The original house was a small, two-story stone structure with a gable roof. A short distance away, at the northeast corner, stood a detached kitchen building. When Joseph Hewes was five years old (1735) the main house burned, but was rebuilt. Other major additions were made in 1753. The house now provides a fine example of Georgian architecture. It was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1971. In1993-94 the building was restored and a frame wing was added to the North side. It is in Mercer County, 346 Snowden Lane, Princeton.

Little is known of Joseph’s early life, except that he, like most Quaker children, helped with the farm work. He received a strict religious upbringing in the Quaker family and had a public education. At a proper age he became a member of Princeton College and after graduation was placed in the counting house of a gentleman at Philadelphia, to be educated as a merchant. When his term of apprenticeship ended, he decided to go into the mercantile business on his own. It was not long before he had made a small fortune.

At the age of thirty Hewes moved to North Carolina. Before this move, he had been residing at New York and Philadelphia alternately, with visits to his friends in New Jersey. He moved to Wilmington, North Carolina in 1760 and established a prosperous shipping and mercantile business. He later moved to Edenton, North Carolina in 1763, where his business interest continued to prosper. In Edenton his shipping business was located on the corner of Main and King Streets. He formed a partnership there with Robert Smith, a lawyer, and the firm soon owned a wharf and their own ships. His first ship was named “Providence” after his mother.

He became engaged to Isabella Johnston. She was a sister of Samuel Johnston who served as one of North Carolina’s governors. Unfortunately, she died shortly before the date of their wedding. He never married and remained a bachelor the rest of his life. After her death, Hewes continued to be a steadfast friend of the Johnston family.

Joseph Hewes sustained a reputation as a man of honor. He acquired the confidence and esteem of the people among whom he lived. Within three years after his arrival in Edenton, Hewes was so highly regarded that he was elected to membership in the Assembly called to represent them in the Colonial Legislature of the province. He served from 1766 until that body ceased meeting in 1775.

In 1774, Hewes was elected to represent North Carolina in the Continental Congress that was assembling in Philadelphia. He was a member of the committee to “state the rights of the colonies.” In this, He assisted in preparing the North Carolina’s celebrated report known later as the “Halifax Resolves,” which like the Declaration of Independence, carefully delineated grievances against the mother country by highlighting misdeeds that justified severing the relationship between themselves and Great Britain.

Because of his shipping interests with England for over twenty years, Hewes was well known outside North Carolina. Though it meant personal loss, when he became involved in activities leading up to the Revolutionary War, Hewes supported a policy of ceasing commercial relationships with Britain. He cheerfully assisted in forming a plan for non-Importation.

In the beginning of 1775, the Society of Friends (the Quakers), to which he and his family belonged, held a general convention denouncing the proceedings of Congress. Hewes, being a true Patriot, came to feel that a revolution in the Colonies was inevitable. He severed his connection with the Society and became a promoter of war against Britain. He threw off other restraints also imposed by the Quakers. He went to dances whenever possible, and it is said that he appreciated the company of the ladies.

On the advice of the committee appointed October 5, 1775, Congress voted to fit out four vessels, A committee of seven was formed by Congress for the defense of the United Colonies. By this vote, Congress was fully committed to the policy of maintaining a naval armament. This committee was the first executive body for the management of naval affairs. It was known as the “Naval Committee” and the members were John Langdon of New Hampshire, John Adams of Massachusetts, Stephen Hopkins of Rhode Island, Silas Deane of Connecticut, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, Joseph Hewes of North Carolina, and Christopher Gadsden of South Carolina. Hewes chaired the committee that was responsible for fitting out the first American Warships. He also put his entire fleet at the disposal of the Continental Armed Forces. The disbursements of the Naval Committee were under his special charge, and eight armed vessels were fitted out with the Funds placed at his disposal.

North Carolina, on April 12, 1776, authorized their delegates to the Continental Congress to vote for independence. This was the first official action by a Colony calling for independence. The 83 delegates present in Halifax at the Forth Provincial Congress unanimously adopted the “Halifax Resolves”. The Resolves were important not only because they were the first official action calling for independence, but also because they were not unilateral recommendations. They were instead recommendations directed to all the colonies and their delegates assembled at the Continental Congress in Philadelphia.

In May, 1776, Hewes presented the Halifax Resolves to the Continental Congress. The last Line of the document reads:

“Resolved that the delegates for this Colony in the Continental Congress be empowered to concur with the other delegates of the other Colonies in declaring Independency, and forming foreign alliances, resolving to this Colony the sole, and exclusive right of forming a Constitution and Laws for this Colony and appointing delegates from time to time (under the direction of a general Representation thereof) to meet the delegates of the other Colonies for such purposes as shall be hereafter pointed out.”

Hewes, who considered the resolves premature, ignored his state’s commitment and at first opposed Richard Henry Lee’s June seventh independence resolution. According to John Adams, however, at one point during debate a transformation came over Hewes. “He started suddenly upright,” reported Adams, “and lifting both his hands to Heaven, as if he had been in a trance, cried out, “It is done! and I will abide by it.”

In a letter to his friend James Iredell on June 28. 1776, Hewes expressed his confidence in the forthcoming debate on independence, “On Monday the great question of independence and Total Separation from all political intercourse with Great Britain will come on, it will be carried I expect by a great Majority and then I suppose we shall take upon us a New Name.”

Joseph Hewes was a friend and benefactor of John Paul (alias Jones). John Paul was a ship boy on a merchantman from Scotland, and at twenty-one was master of a Brigantine. He arrived in America in 1773. and became a friend of Joseph Hewes. When the time came to appoint the Nation’s first Naval captains, Hewes and John Adams clashed for one of the positions. Hewes nominated his friend John Paul Jones. John Adams maintained that all the captaincies should be filled by New Englanders, and stubbornly protested. New England had yielded to the South in the selection of a commander in chief of the Continental Army and Adams had fostered the selection of the able Virginian George Washington, so he was not now about to make a concession on the Navy. Hewes, sensing the futility of argument, reluctantly submitted. John Paul Jones, was to become the most honored Naval hero of the Revolution, but he received only a Lieutenant’s commission. Jones never forgot his patron and sponsor and many letters are extant telling of the great gratitude he felt for Hewes’ interest in him. The following is an excerpt from one of the letters: “You are the angel of my happiness; since to your friendship I owe my present enjoyments, as well as my prospects. You more than any other person have labored to place the instruments of success in my hands.” (John Paul Jones)

In 1776, Hewes was a member of the secret committee, of the committee on claims, and was virtually the first secretary of the Navy. John Adams, would often boast that he and Hewes “laid the foundation, the cornerstone of the American Navy.” With General Washington, Hewes conceived the plan of operations for the ensuing campaign, and voted in favor of the immediate adoption of the declaration, North Carolina being the first in the colonies to declare in favor of throwing off all connection with Great Britain. He was also on the committee to prepare the Articles of Confederation.

Hewes was not selected as a delegate to the Continental Congress in 1777.

Despite this, the Assembly employed Hewes to fit out two vessels. He declined, however, because he was already an agent for the Continental Congress regarding shipping. When the House of Commons met in 1779 Hewes was again there as an elected member of the House of Commons.

A letter signed “G. Washington” as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army to Joseph Hewes, August 25, 1779, responds to Hewes’ asking Washington to help gain the “enlargement” (release) of a friend (Mr. Granberry) captured by the British. Washington replied with his opinion that trading captured British soldiers for captured American civilians would only motivate the British to capture more civilians.

Because of his poor health, Hewes sent his resignation to the General Assembly in late 1779. However, he died In Philadelphia on November 10, 1779 before he could return to his home in Edenton, NC. He was the only signer of the Declaration of Independence who died at the seat of government. His remains were followed to the grave in Christ Church Cemetery by Congress in a body, and a large concourse of the citizens of Philadelphia. Congress resolved that they would “attend the funeral with a crape round the left arm, and continue in mourning for one month.” It was suggested that a committee also be appointed to superintend the ceremony, and that the Rev. Mr. White, their chaplain, should officiate on the occasion. Today a marker commemorates Hewes, but the site of his grave is unknown.

Biography credit here.

Final Thoughts

Joseph Hewes exemplified the personal sacrifices and transformative moments that defined America’s founding generation. As a prosperous Quaker merchant with extensive business ties to Britain, he had every reason to oppose independence. Yet when the moment of decision arrived, Hewes cast aside religious tradition, commercial interests, and personal fortune to embrace the revolutionary cause. His dramatic conversion during the independence debate—suddenly standing and declaring “It is done! and I will abide by it”—captures the profound internal struggles many colonists faced as they chose between loyalty to the crown and the uncertain promise of self-governance.

Hewes’s contributions to American independence extended far beyond his signature on the Declaration. As a key architect of the Continental Navy alongside John Adams, he helped establish the maritime force that would prove crucial to winning the Revolutionary War. His championing of John Paul Jones, despite regional politics, demonstrated his ability to recognize talent and prioritize merit over parochialism. Through his work on committees for claims, confederation, and naval affairs, Hewes provided the practical expertise and administrative skill necessary to transform revolutionary ideals into functioning government institutions.

The tragedy of Hewes’s personal life—losing his fiancée and remaining a lifelong bachelor—perhaps freed him to devote himself entirely to public service. He died at just 49, worn down by years of tireless work for the new nation, becoming the only signer to die at the seat of government while still serving. Though he left no direct descendants to preserve his memory, his legacy lives on in the institutions he helped create and the nation he helped birth. Joseph Hewes reminds us that the American Revolution succeeded not just through grand speeches and battlefield heroics, but through the quiet dedication of practical men who sacrificed everything for a cause greater than themselves.

Thanks for reading!