T.L.D.R. –

- Age at Signing: 44

- Occupation: Planter

- Key Perspective/Position: Introduced independence resolution

- Personal Sacrifice: Brother also signed

- Unique Contribution: Without him, no Declaration

Introduction

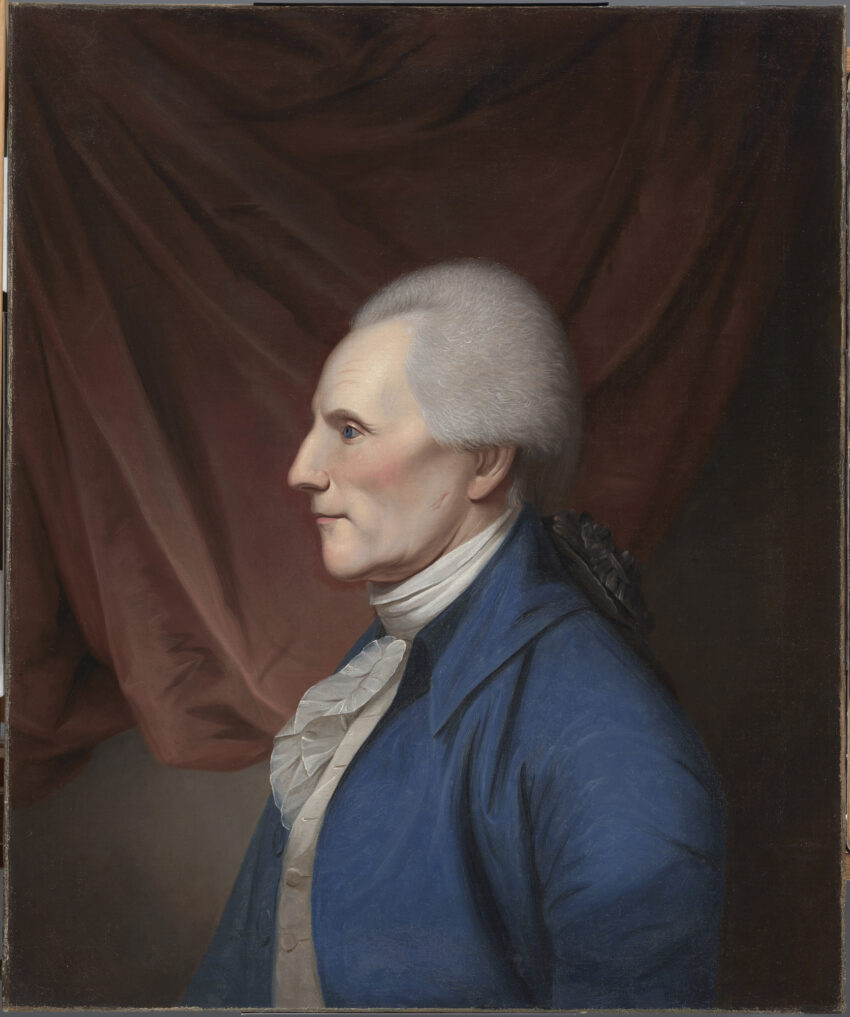

Richard Henry Lee was born on January 20, 1732, at Stratford Hall, Virginia, into the prominent Lee political dynasty. Educated at home then in England, he returned to Virginia in 1753. He married Anne Aylett and later Anne Gaskins Pinckard, having six children.

Lee entered public life as a justice of the peace and House of Burgesses member. Alongside Patrick Henry, he became an early advocate for independence, speaking against British taxation. His greatest moment came on June 7, 1776, when he introduced the resolution declaring “these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States.”

Lee served as president of Congress from 1784-1785 and was elected one of Virginia’s first U.S. Senators in 1789, briefly serving as president pro tempore. He resigned in 1792 due to declining health and died on June 19, 1794, at age 62 at his estate in Chantilly, Virginia.

Contribution to Independence: Lee’s resolution on June 7, 1776, formally proposed independence, setting in motion the events leading to the Declaration. Without his resolution, there would have been no Declaration to sign.

A Brief Biography

Tall, slim with reddish hair, Richard Henry Lee was comfortable with speaking his opinion to the public.

Born in 1732, Lee grew up at Stratford Hall, an enormous tobacco plantation in Westmoreland County, Va. His parents, Thomas, and Hannah Ludlow Lee, hired Scottish ministers to tutor their eight children. The boys were not always allowed to sleep in the impressive brick Great House, but above their school room in a separate building. Often, classes started before breakfast and ended at 5pm each day.

Understanding Great Britain made sense to the Lee family. Richard Henry’s great-grandfather, Richard Lee, had left England in 1639 bound for Jamestown, Va., to develop a successful trade with Lees on both sides of the Atlantic. It was important to Thomas and Hannah to send their children to England to educate them and to teach the customs and law. When Richard Henry was 16, he and his older brothers sailed to England in a Lee tobacco ship. He never saw his parents again: Both died in 1750. Richard Henry finished his schooling at Wakefield Academy in Yorkshire and took a brief European trip before he sailed home to Virginia. He was particularly impressed by a beautiful home outside Paris named “Chantilly.”

His oldest brother, Philip Ludwell Lee, inherited the Stratford Hall plantation while Richard Henry inherited 50 slaves and land in northern Virginia. Richard Henry chose to stay at the Great House, and leased his inherited land to tenant farmers. The Lee children also inherited company shares planned to speculate land in the Ohio River valley. Richard Henry continued to study ancient classics and modern history, later quoting both in his speeches and his writing.

At age 23, Lee raised a military company to support British Gen. Edward Braddock during the French and Indian War. Fortunately for Lee, Braddock refused the support before he was killed in the summer of 1755. In time, Lee learned that his leadership would be needed both for military and public service. Two years later, Lee was appointed justice for Westmoreland County.

In 1758, Lee was elected member of the House of Burgesses, an office that he held most of the rest of his life. On Dec. 3, he married Anne Aylett, and leased land about three miles away from Stratford Hall from brother Philip. They designed and built a three-story, 10-room home named “Chantilly-on-the-Potomac.”

Lee’s first speech was against the transportation of slaves to Virginia. “And well am I persuaded, Sir, that if it be so considered, it will appear, both from reason and experience, that the importation of slaves into this Colony has been and will be attended with effects dangerous both to our political and moral interests,” he said. He suggested increasing the taxes. “Lay so heavy a tax upon the importation of slaves as effectually to put an end to that iniquitous and disgraceful traffic within the Colony,” he told the Burgesses.

His decisions were not always wise. Tobacco prices dropped then fluctuated, and Anne and Richard Henry’s family grew. He forged new opportunities to make money for the family. Knowing little about the Stamp Act, Lee applied to be a tax collector in 1764. Too late he began to understand what “Taxation without Representation” meant to the colonies. He agreed when his colleague, Patrick Henry, spoke against the Stamp Act in May 29, 1765, in the House of Burgesses: “Caesar had his Brutus; Charles I, his Cromwell; and George III [cries of “Treason” from the crowd] may profit by their example. If this be treason, make the most of it.”

Later, Lee was censured by the House about his earlier interest in collecting the Stamp Act. He defended himself July 15, 1766. “I believe… no more than myself, nor perhaps a single person in this country, has at that time reflected the least on the nature and tendency of such an act.” Forgiven, he moved ahead, writing the Westmoreland Resolution of 1766, binding citizens to support “our lawful sovereign, George the Third…so far as is consistent with the preservation of our rights and liberty.” Many considered the Resolution seditious as Lee challenged the king. Later, his Resolution gave guidance to those who wrote the Declaration of Independence.

The year 1768 was tragic. His wife, Anne, died Dec. 12, leaving four young children: Thomas, Ludwell, Mary, and Hannah. During the winter, Lee went goose hunting, one of his favorite sports. His gun exploded in his left hand, and he lost those four fingers. He began to use black silk, either wrapping the damaged hand with a handkerchief or using a black glove to cover the wound. Thinking positively, Lee began to draw attention during his speeches, raising and pointing his injured hand.

During the summer of 1769, Lee married again: a widow, Anne Gaskins Pinckard, a descendant of three Mayflower pilgrims. She had two children of a previous marriage. The couple had two sons and three daughters: Anne, Henrietta, Sarah, Cassius, and Francis Lightfoot, bringing the number to 11 children.

Lee was elected to a Williamsburg convention opening Aug. 1, 1774. They discussed disagreements with Great Britain, and elected delegates for the first Continental Congress to be held Sept. 4, 1774, in Philadelphia. George Washington took notes on the voting: “Peyton Randolph 104, Richard Henry Lee 100, George Washington 98, Patrick Henry 89, Richard Bland 79, Benjamin Harrison 66, Edmund Pendleton 62.”

Lee’s speeches were often powerful, academic, and sometimes spontaneous. “The great orators here,” wrote John Adams, “are Lee, Hooper and Patrick Henry.” St. George Tucker of Virginia described Lee’s speeches: “The fine powers of language united with that harmonious voice, made me sometimes think that I was listening to some being inspired with more than mortal powers of embellishment.” Lee and Adams became a powerful team, often meeting with Adams cousin, Samuel Adams, at Lee’s sister’s house in Philadelphia. Sister Alice had married physician William Shippen, Jr., who would become America’s chief medical officer in the Revolution.

The year 1775 was significant. Brother Philip died Feb. 21, and Richard Henry was the executor, taking on the care of his brother’s family, as he did for most of his siblings. He traveled extensively from home to Philadelphia and to Richmond, Va. Lee was at St. John’s Church in Richmond March 23 when Patrick Henry spoke his classic “Liberty or Death” speech. On April 20, 1776, Lee wrote to Patrick Henry, urging Virginians to lead the colonies to force independence. He quoted many of the words above in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, with few changes. “There is a Tide in the Affairs of Men, which taken at the Flood leads on to Fortune—That omitted, we are ever after bound in Shallows.”

In Virginia, the Convention met May 6, voted for independence, and sent instructions to Philadelphia May 15. On June 7, as head of the Virginia delegation, Lee rose and made a powerful motion: “That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.” John Adams seconded. Congress postponed a debate till July 1, allowing a committee to write a proposed declaration of independence based on Lee’s Westmoreland Resolutions.

The British papers went wild. “Richard Henry Lee and Patrick Henry have at last accomplished their object: The colonies have declared themselves independent of the mother country,” was published. Pressure was building from Virginia. Letters poured in to Richard Henry. “I wish to divide you, and have you here…and in Congress,” wrote Patrick Henry from Williamsburg. John Page wrote, “Would to God you could be here.” George Mason wrote, “We are now going upon the most important of all subjects—government! Mr. Nelson is now on his way to Philadelphia and will supply your place in Congress…Let use see you here as soon as possible…We cannot do without you.”

Lee was very aware of being needed from several political worlds. Immediately after his motion, he shared ideas with the Drafting Committee and chaired a second committee to write the Articles of Confederation, the first constitution for the United States. Lee represented Virginia as each state chose one delegate to form the 13-person committee. But he was called to rush to Williamsburg to assist June 13, confident that his colleagues Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Nelson were quite capable. Lee was not in Philadelphia for the vote July 4, but returned with many others including his brother, Francis Lightfoot Lee, to sign the Declaration of Independence in August.

When Lee returned to Congress, he was an active participant in the debates on many controversial subjects including state boundaries, taxation, and the powers of the proposed central government. Finally, the Articles were approved and Lee signed the Articles on Nov. 15, 1777: One of just 15 signers of the Declaration to do so.

There were enemies, who spoke against Lee in Virginia and in Congress. Faulty rumors spread that Lee and others were attempting to depose friend George Washington’s leadership. He was inappropriately blamed to speculate land out west, using the company shares he and his siblings had inherited from their father. He was accused of misuse of his public office for personal gain there and against his Northern Virginia tenants.

Lee was consistent in proving his and his family’s honor. Defeated in 1777 when Virginians chose the next Continental Congress delegates, Lee requested a formal investigation. The Assembly granted his investigation, and he was acquitted. His old friend George Wythe, then Speaker, explained the results during the Assembly. “Serving with you in Congress…you manifested in the American cause a zeal truly patriotic…That the tribute of praise deserved may reward those who do well and encourage others to follow your example, the House have come to this resolution: ‘Resolved, That the thanks of this House be given by the Speaker, to Richard Henry Lee, Esq., for the faithful service he has rendered to his country, in discharge of his duty, as one of the delegates from this State in general Congress.’ ”

Lee thanked the House’s “candor and justice.” He said, “I consider the approbation of my country, Sir, the highest reward of faithful services, and it shall be my constant care to merit that approbation by a diligent attention to public duty.”

Military leadership was required to protect Lee’s home and family property. During the spring of 1781, the British burned houses and tobacco warehouses along the Potomac River. Richard Henry was re-commissioned as colonel in the Westmoreland militia, moving his family away from Chantilly as disaster was expected. Observing three British ships approaching the Stratford wharf, he called up the militia. As the British embarked, the Americans fired. At least one British troop was killed and others were wounded as the British retreated. “I am at present lamed by my horse falling on me in a late engagement with the enemy who landed under cover of heavy cannonades from three vessels of war upon a small body of our militia were posted,” wrote Lee to his friend Samuel Adams April 1. “After a small engagement we had the pleasure to see the enemy, tho superior in numbers, run to their boats and precipitately reembark having sustained a small loss of killed and wounded.”

Despite his painful feet, Lee returned to Congress in 1784. He was immediately chosen president of the Continental Congress. He and many southern tobacco planters worked to limit federal powers. He and many Virginians including George Mason, Patrick Henry, Benjamin Harrison, and Thomas Jefferson opposed the adoption of the Constitution. In 1788, Virginia voted 88-79 in favor, becoming the 10th state to approve the Philadelphia plan.

Lee and William Grayson were elected Virginia’s first U.S. senators in 1789. He encouraged the first 10 amendments, and was successful. However, his health declined after his right hand was so affected, he required a personal secretary. Then his carriage turned over in the fall of 1791. He did not resume his seat until December 1791, and ended his work there when Congress adjourned May 7, 1792.

He continued as a member of the Virginia Assembly until he retired from public life in 1792 with a unanimous resolution of appreciation from the House of Delegates.

Richard Henry Lee died at “Chantilly” June 19, 1794. He was buried at the family cemetery at “Burnt House Field,” about 20 miles away.

Biography credit here.

Final Thoughts

Richard Henry Lee’s legacy extends far beyond his famous resolution that sparked American independence. His story embodies the complexities of the Revolutionary era—a Virginia planter who owned slaves yet spoke against the slave trade, a member of the colonial elite who risked everything to challenge British authority, and a political leader who helped create a new nation while later opposing its Constitution. Lee’s physical sacrifices, from losing four fingers in a hunting accident to suffering injuries defending his home against British forces, serve as tangible reminders that the Founding Fathers paid personal prices for their political convictions. His ability to turn disadvantage into rhetorical power—dramatically gesturing with his silk-wrapped injured hand during speeches—reveals a man who understood that revolution required both intellectual arguments and theatrical persuasion.

The Lee family’s contribution to American independence was truly a family affair, with Richard Henry and his brother Francis Lightfoot both signing the Declaration, making them the only siblings to share this distinction. Yet Richard Henry’s most crucial contribution came not from his signature but from his June 7, 1776 resolution declaring the colonies “free and independent States.” Without this formal motion, there would have been no Declaration to draft, no document to sign, no founding text to inspire generations. His work didn’t end with independence; Lee helped draft the Articles of Confederation and later championed the Bill of Rights, showing a consistent concern for limiting governmental power that reflected his Virginia planter worldview.

Lee’s life reminds us that the American Revolution was not inevitable but required individuals willing to take bold action at critical moments. His classical education, evident in his speeches peppered with references to Caesar and Shakespeare, connected the American cause to the great political dramas of history. From Stratford Hall to the Continental Congress, from colonial legislator to U.S. Senator, Lee’s journey illustrates how personal ambition, family obligation, and patriotic duty intertwined in the founding generation. His death in 1794 at his beloved Chantilly estate marked the end of a life dedicated to what he called “the American cause,” leaving behind a complex legacy of revolutionary leadership and the fundamental tension between liberty and slavery that would continue to shape the nation he helped create.

Thanks for reading!