Tungsten is a very dense, corrosion-resistant metal that is almost impossible to melt. In fact, tungsten has the highest melting point of all metals. Tungsten exhibits other important physical properties as well, including good thermal and electrical conductivity, a low coefficient of expansion, and exceptional strength at elevated temperatures.

This amazing metal sees essential use in many applications, including but not limited to: armaments such as bullets and missiles, heat sinks, high-density applications such as counterweights, superalloys for turbine blades, tool steels used in saw blades and drill bits, electrical furnaces, spacecraft, metal evaporators, x-ray equipment, and making glass-to-metal seals. Tungsten chemical compounds are used in catalysts, inorganic pigments, and high-temperature lubricants.

Because of tungsten’s many desirable properties and important applications, and because tungsten is not found free in nature, industrialized countries around the world consider tungsten to be a Critical Resource Mineral essential for national sovereignty.

Be sure to check out all other critical raw materials (CRMs), as well.

Beyond the basics above, what else should we know about tungsten? Check out the 20 interesting facts below!

- In the Middle Ages (16th century) tin miners in the Saxony-Bohemian Erzgebirge in Germany reported about a mineral which often accompanied tin ore (tinstone). From experience, it was known that the presence of this mineral reduced the tin yield during smelting. Foam appeared on the surface of the tin melt and a heavy deposit formed in the smelting stove, which retained the valuable tin. “It tears away the tin and devours it like a wolf devours a sheep”, a contemporary wrote. The miners gave this annoying ore German nicknames like “wolffram”, “wolform”, “wolfrumb” and “wolffshar” (because of its black colour and hairy appearance). Georgius Agricola was the first to report this in his book “De Natura Fossiliumâ€, published in 1546.

- Tungsten’s chemical symbol is “Wâ€, which comes from the element’s long-time name, “wolframâ€. The element name wolfram came from the name of the ore, wolframite, which derives from the German wolf’s rahm, which means “wolf’s foam”.

- The use of tungsten as coloring material for porcelain was practised in the reign of Chinese emperor Kang-his (1662-1722). The Imperial Court of Emperor Kang-his ordered the best of the well-known porcelain kilns in the Province of Kiangsi at Ching Te Cheng (China) to manufacture eight forms of porcelain in the color of peach bloom. This peach-bloom color is particularly hard to produce in porcelain. It is neither pink nor red. It is a combination of pink and red with a suggestion of green. The Chinese call it Mei-Jen Chi, or maiden blush.

- The name “Tungsten†came from an important tungsten ore, now called scheelite. In 1750, this heavy mineral was discovered in the Bispberg´s iron mine in the Swedish province Dalecarlia. The first person who mentioned the mineral was Axel Frederik Cronstedt in 1757, who called it “Tungsten†, or “heavy stone†(composed of the two Swedish words “tungâ€, or “heavyâ€, and “stenâ€, or “stoneâ€, due to its density).

- In 1781, chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele published the results of his experiments on tungsten. In this work, he demonstrated that the mineral contained lime and a still unknown acid, which he called tungstic acid.

- In 1783, Spanish nobleman Juan José de D´Elhuyar analyzed wolfram from a tin mine in Saxony and showed it to be an iron and manganese salt of a new acid. He also concluded that wolfram contained the same acid that Carl Wilhelm Scheele had gained from tungsten.  He then reduced the oxide to the new metal by heating it with charcoal. His discovery, jointly with his brother Fausto Jermin, was published in 1783 by the Royal Society of Friends of the Country in the City of Victoria (“Analysis quimico del volfram, y examen de un Nuevo metal, que entra en su composition por D Juan Joséf y Don Fausto de Luyart de la Real Sociedad Bascongadaâ€).  The new metal was named “VOLFRAM†after the mineral used for analysis.

- In 1847, an important patent was granted to the engineer Robert Oxland for the preparation of sodium tungstate, the formation of tungstic acid, and the reduction to the metallic form by oil, tar or charcoal. The work opened the way to industrialization.

- Tungsten-containing steels were patented in 1858, leading to the first self-hardening steels in 1868.

- 1895: Thomas Edison investigated materials’ ability to fluoresce when exposed to X-rays, and found that calcium tungstate was the most effective substance.

- Revolutionizing engineering of the early 20th century, high-speed steels with tungsten additions up to 20% were first demonstrated at the World Exhibition in Paris in 1900.

- The first tungsten light bulbs were patented in 1904. William Coolidge and his team at General Electric are successful in discovering a process that created ductile tungsten filaments through suitable heat treatment and mechanical working in 1909.

- 1914: During World War I, the first widespread use of tungsten in armaments, which was eventually accompanied by very high prices, stimulated production in the United States and launched the Chinese tungsten mining industry. “It was the belief of some Allied military experts that in six months Germany would be exhausted of ammunition. The Allies soon discovered that Germany was increasing her manufacture of munitions and for a time had exceeded the output of the Allies. The change was in part due to her use of tungsten high-speed steel and tungsten cutting tools. To the bitter amazement of the British, the tungsten so used, it was later discovered, came largely from their Cornish Mines in Cornwall.†– From K.C. Li’s 1947 book “TUNGSTENâ€

- 1923: A German electrical bulb company submitted a patent for tungsten carbide, or hardmetal. It was made by “cementing†very hard tungsten monocarbide (WC) grains in a binder matrix of tough cobalt metal by liquid phase sintering. The result changed the history of tungsten: a material which combined high strength, high toughness and high hardness. In fact, tungsten carbide is so hard, the only natural material that can scratch it is diamond.

- 1942: During World War II, the Germans were the first to use tungsten carbide in high velocity armor piercing projectiles. British tanks virtually “melted†when hit by these tungsten carbide projectiles.

- In 2005, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry dropped the name “wolfram†entirely to make the periodic table the same in all countries. This is probably one of the most highly disputed name changes ever made to the periodic table. Since then, only the name “tungsten†has been used.

- In May 2018, the U.S. Department of the Interior, in coordination with other executive branch agencies, published a list of 35 critical minerals (83 FR 23295), including tungsten. This list was developed to serve as an initial focus, pursuant to Executive Order 13817, ‘‘A Federal Strategy to Ensure Secure and Reliable Supplies of Critical Minerals†(82 FR 60835).

- 80 percent of world’s tungsten supply is controlled by China.

- Tungsten has the highest melting point (6191.6 °F or 3422 °C), the lowest vapor pressure, and the highest tensile strength of all metals. Tungsten is also extremely dense – with a density within 0.36 percent that of gold.

- Tungsten is one of the five refractory metals. The other metals are niobium, molybdenum, tantalum, and rhenium. Refractory metals are those which exhibit extremely high resistance to heat and wear.

- Discoveries in tungsten use can be loosely linked to four fields: chemicals, steel and super alloys, filaments, and carbides. In 2018, Nearly 60% of the tungsten consumed by the United States was used in cemented carbide parts for cutting and wear-resistant applications, primarily in the construction, metalworking, mining, and oil and gas drilling industries. The remaining 40% of tungsten was used to make various alloys and specialty steels, electrodes, filaments, wires, and other components for electrical, electronic, heating, lighting, welding, and chemical applications.

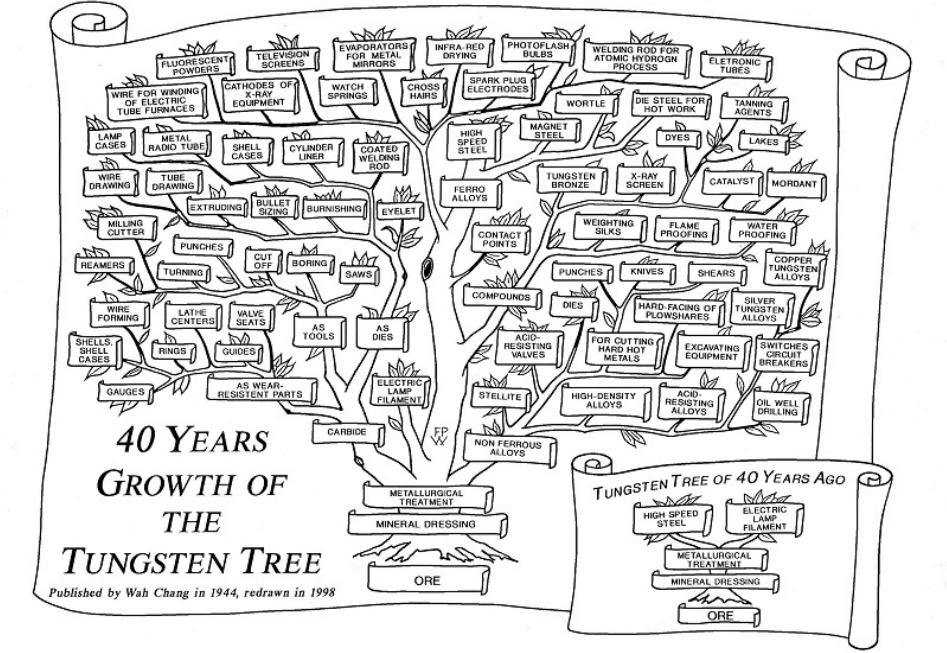

In 1944, K C Li, President of Wah Chang Corporation in the U.S., published a picture in the Engineering & Mining Journal entitled: “40 Years Growth of the Tungsten Tree (1904 – 1944)†illustrating the fast development of the various tungsten applications in the field of metallurgy and chemistry.