T.L.D.R. –

- Age at Signing: 32

- Occupation: Merchant

- Key Perspective/Position: Initially refused to sign Constitution

- Personal Sacrifice: Palsy made signing difficult

- Unique Contribution: Later VP; “gerrymandering” named for him

Read about the lives of the other signers of the Declaration of Independence here – ‘Who Were The Signers Of The Declaration Of Independence?’

Introduction

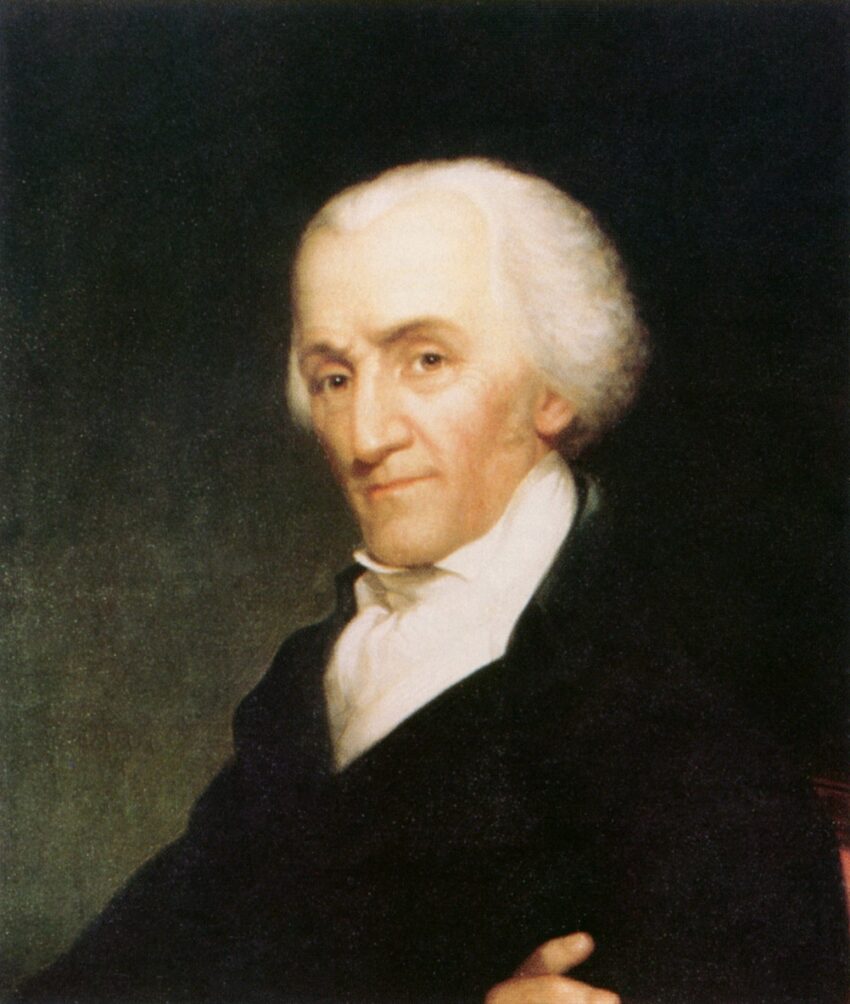

Elbridge Gerry was born on July 17, 1744, in Marblehead, Massachusetts, into a family of successful merchants. He graduated from Harvard College and initially worked in commerce with Samuel Adams before entering public service as a member of the Massachusetts Legislature and General Court. He married Ann Thompson in 1786 and had seven children.

In 1775, Gerry was elected to the Second Continental Congress, where he signed the Declaration of Independence and served until 1780. He concentrated on military and supply matters during his congressional service. At the Constitutional Convention in 1787, he chaired the committee that created the Great Compromise but refused to sign the Constitution without a Bill of Rights, alongside Edmund Randolph and George Mason.

Gerry served two terms in Congress after ratification, retiring in 1793. In 1797, he participated in the diplomatic mission to France that resulted in the XYZ Affair. He served as Governor of Massachusetts beginning in 1810, where redistricting decisions under his administration led to the term “gerrymandering.” In 1813, he became Vice President under James Madison, serving until his death on November 23, 1814, at age 70.

Contribution to Independence: Gerry signed the Declaration despite suffering from palsy that caused his hand to tremble. He later played a crucial role in forging the constitutional compromises that created the federal system.

A Brief Biography

Elbridge Gerry was born on July 17, 1744 at Marblehead, Massachusetts, the third son of Thomas Gerry and Elizabeth Greenleaf. Elbridge’s father, Captain Thomas Gerry, was born in 1702 and came to America in 1730 from Newton Abbott, Devonshire, England. He was master of his own vessel and became a wealthy and politically active merchant shipper. Thomas was a pillar of the Marblehead community, serving as a justice of the peace, selectman and as moderator of the town meeting. On December 16, 1734, he married Elizabeth Greenleaf, the daughter of a Boston merchant. The Gerry family was pious, faithfully attending the First Congregational Church and avoiding ostentatious display.

Gerry’s great-great-grandfather, Edmond Greenleaf, was born in Malden, England, came to America in 1635 and settled in Newbury. He and his family removed to Boston in 1650. One of his descendants was the famous New England poet, John Greenleaf Whittier.

Little is known of the childhood of Elbridge Gerry. He entered Harvard College at the age of 14 and graduated in 1762, ranking 29th in a class of 52. Elbridge went on to receive a Master’s degree in 1765 at the age of 20. His Master’s dissertation argued that America should resist the recently passed Stamp Act.

Upon graduation, Elbridge entered his father’s counting house. The Gerrys owned their own vessels and shipped dried codfish to the Barbados and Spanish Ports, and returned with bills of exchange and goods. He eventually became one of the wealthiest and most enterprising merchants in Marblehead. The Encyclopedia of American Wealth ranks Gerry 11th in wealth among the 56 signers of the Declaration.

Gerry’s first venture into politics occurred in 1770 when he served on a local committee to enforce the ban on the sale and consumption of tea. In December 1771, his father Thomas Gerry moderated a meeting in Marblehead of the new Committee of Correspondence to discuss the resolves put forward by Samuel Adams. Elbridge joined his father there and helped craft the fiery resolves that were adopted. In May 1772, Elbridge was elected representative to the General Court and met Sam Adams, with whom he immediately bonded. When Parliament closed the port of Boston in June 1774, Marblehead became a major port of entry for goods and supplies, which Gerry then transported to Boston. Mercy Otis Warren stated that Gerry coordinated the procurement and distribution of arms and provisions with “punctuality and indefatigable industry.”

In 1774, Gerry was appointed to the Provincial Congress where he was appointed to the Executive Committee of Safety. On the famous night of April 18, 1775, when Paul Revere rode into history and poetry, Gerry and two American colonels were in bed at the Menotomy Tavern, after a meeting there of the Committee of Safety. The Tavern was on the road which the British took to Lexington. When a detachment of redcoats stopped to search the house, Gerry and his companions escaped in their night clothes and hid in a nearby cornfield.

During the remainder of 1775, Gerry remained in Boston, helping to raise troops and supplies for the Provincial army. Gerry submitted a proposal in the Provincial Congress for a law to encourage the fitting out of armed vessels and to provide for the adjudication of prizes. For a colony to authorize such an act was rebellious if not treasonable. John Adams pronounced this law one of the most important measures of the Revolution. Under its provisions, Massachusetts vessels captured several British ships, procuring cargoes and supplies needed by the colonies.

Elbridge Gerry was elected a delegate to the Second Continental Congress and took his seat there on February 9, 1776. Gerry’s efforts to persuade delegates from the middle colonies to support independence, earned praise from John Adams: “If every Man here was a Gerry, the Liberties of America would be safe against the Gates of Earth and Hell.” Gerry voted for independence on July 2, and signed the engrossed copy of the Declaration of Independence on September 3.

Gerry was re-elected to Congress in 1777 and signed America is first constitution, the Articles of Confederation, on November 15, 1777. He was one of only 16 members of Congress who signed both the Declaration and the Articles. Gerry remained in Congress, technically speaking, until 1785. However, in 1780 he was offended by actions that he felt impinged on states’ rights and withdrew from Congress. He resumed his seat in 1783. During his time in Congress, he earned the nickname “soldiers’ friend” for his advocacy of better pay and equipment, and was recognized as a diligent legislator.

But he was also viewed as a maverick by some. Adams criticized him for his “obstinacy that will risk great things to secure small ones,” and Secretary Thomson observed that “his pleasure seems proportioned to the absurdity of his schemes.” Along with his friend Robert Treat Paine, Gerry supported resolutions against theatrical entertainment and horse racing, and those favoring days of fasting, humiliation, and prayer.

After leaving Congress, Elbridge Gerry married Ann Thompson on January 12, 1786, and they had nine children. Ann was the daughter of New York merchant James Thompson and Catharine Walton. Ann’s grandfather, Jacob Walton, first married Maria Beekman, and later Polly Cruger. Both wives were members of distinguished colonial families in New York. In the same year 1786, Gerry acquired the Cambridge home of a former loyalist official and Harvard graduate, and moved his family there from Marblehead. The Gerrys called this their home until the death of Elbridge in 1814. Ann Thompson lived until 1849, becoming the oldest surviving widow of a signer of the Declaration of Independence. She is buried in the Old Cemetery in New Haven, Connecticut.

In 1786, Gerry took his seat in the Massachusetts House of Representatives, and in 1787, he attended the Federal Convention in Philadelphia that produced the new Constitution of the United States. At first, he advocated a strong central national government, but then changed his mind as the form of the Constitution developed. He believed that both the executive and legislative branches of government were granted ambiguous and dangerous powers, and he refused to sign the Constitution. Gerry published his anti-Federalist beliefs in Observations on the New Constitution and on the Federal and State Conventions.

Overcoming his objections to the Constitution, Gerry served in the House of Representatives from 1789 to 1793. To the dismay of his anti-federalist friends, he supported the Federalist agenda, including Hamilton’s proposals to fund the War debt and establish a national bank.

On June 20, 1797, President John Adams sent Gerry along with Charles Pinckney and John Marshall to France, to negotiate a peace treaty with Talleyrand, Napoleon’s new foreign minister. The mission was a disaster, with the French trying to bribe the American commissioners, and came to be known as the XYZ affair with the letters representing the three chief French bribers. Finally, the Treaty of Mortefontaine was completed in 1800 and is considered a great achievement by the Adams administration in keeping the United States neutral in the expanding war between Britain and France.

In 1800, maligned by federalists who believed him partial to France, and concerned about the likelihood of Alexander Hamilton becoming General of the army, Gerry joined the moderate wing of the Republican party. He ran for Governor of Massachusetts, a strong Federalist stronghold, in the early 1800s but was unsuccessful.

In 1810, Gerry ran again as the Democratic-Republican candidate and was elected governor of Massachusetts. He was re-elected in 1811, but was defeated in 1812. He had become unpopular after supporting a redistricting bill that gained him lasting fame. By rearranging voting districts around Amesbury and Haverhill to favor the Republicans, the resulting district resembled a salamander, thus earning the famous sobriquet of a “gerrymander.” He also prosecuted Federalist editors for libel and appointed family members to state office—both adding to his unpopularity.

Two weeks after Gerry was defeated in his re-election bid in Massachusetts, he was invited to run as Vice President with President Madison in 1812, and thus became Vice President of the United States. The Madison administration became increasingly unpopular during the War of 1812, and the controversy split the Republican majority in Congress. Gerry found it increasingly difficult to remain impartial in such a highly charged environment, but continued to be an energetic defender of the administration and the war.

Unpleasant as his Senate duties had become, Gerry still enjoyed the endless round of dinners, receptions, and entertainments that crowded his calendar. With his elegant manners and personal charm, the Vice President was a favorite guest of Washington’s Republican hostesses, including first lady Dolley Madison. He maintained an active social schedule that belied his advanced years and failing health, visiting friends from his earlier days who were now serving as members of Congress or in the administration. He paid special attention to Betsy Patterson Bonaparte, the American-born sister-in-law of Napoleon, whose revealing attire caused a stir wherever she went.

On November 23, 1814, Elbridge Gerry died on his way to preside over the Senate in Washington, D.C. Congress paid for his burial expenses, but the partisan House rejected a Senate bill providing the Vice President’s salary to be paid to his widow for the remainder of his term.

Gerry’s monument in the Congressional Cemetery at Washington, D.C. bears this inscription:

The Tomb of

ELBRIDGE GERRY

Vice President of the United States

Who died suddenly in this city on his

way to the Capitol, as President of the Senate

November 23, 1814,

Aged 70

Elbridge Gerry was a small, dapper gentleman possessed of pleasant manners, but never very popular because of his aristocratic traits. He had no sense of humor, frequently changed his mind on important issues, and was suspicious of the motives of others. But he was a conscientious businessman who paid attention to detail. His patriotism and integrity could never be questioned.

While Gerry’s actions can be considered those of a maverick, they can also be viewed as those of a man of principle with independence of thought and action independent of party influence. He signed the Declaration and the Articles of Confederation but vigorously opposed the Constitution. He then served in Congress where he supported Alexander Hamilton’s federalist agenda ensuring the future financial security of the young republic. He became a Republican in 1800, lost several contests for Governor of Massachusetts. But he was elected Madison’s Vice President and stayed loyal to him when most of the Republicans split off over Madison’s handling of the war.

Dr. Benjamin Rush wrote that he was “a genuine friend of republican forms of government.” One of Gerry’s own statements was “I hold it to be the duty of every citizen, though he may have but one day to live, to devote the day to the good of his country.”

The Georgian style Cambridge home of Elbridge Gerry, from 1786 to his death in 1814, has a long and distinguished Harvard pedigree. It stands today at the end of a newly-created dead-end road, a half mile from the Harvard campus. Except for a brief period during the revolutionary era, the house has been the home since 1767 of Harvard graduates, professors, and presidents. The house was built in 1767 by Andrew Oliver, Harvard class of 1753, a former stamp-collector then serving as royal secretary of Massachusetts. Surrounded in his home by an angry crowd in 1774, Oliver resigned his office and soon after left for England. Oliver’s home was confiscated during the revolution and served as a field hospital for Washington’s troops and then the command post of Benedict Arnold.

Gerry, Harvard class of 1762, purchased the house in 1787 and moved his family there from Marblehead. Not long after Gerry’s death in 1814, Harvard graduate James Russell Lowell, who would become a distinguished man of letters and an accomplished diplomat, was born in the house and it became his lifelong home. He named it Elmwood, and it became a National Historic Landmark. Harvard University acquired Elmwood in 1962, and it has been the home of Harvard’s president since 1971.

Biography credit here.

Final Thoughts

Elbridge Gerry’s legacy embodies the complexities and contradictions of America’s founding generation. His refusal to sign the Constitution without a Bill of Rights demonstrated the principled dissent that helped shape our system of governance, while his later support for federalist policies showed his ability to adapt his views for the nation’s benefit. Though history remembers him most for the political maneuvering that gave us the term “gerrymandering,” Gerry’s contributions extend far beyond this dubious distinction. His tireless work supplying the Continental Army, his advocacy for soldiers’ welfare, and his diplomatic service in the XYZ Affair reveal a patriot committed to practical service over ideological purity.

What makes Gerry particularly fascinating is how his career illustrates the messy realities of democratic governance. Unlike some founders who maintained consistent political philosophies, Gerry changed parties, shifted positions, and sometimes contradicted himself—yet always with what he believed were the nation’s best interests at heart. His trembling hand as he signed the Declaration due to palsy serves as a poignant reminder that the founders were flesh-and-blood individuals facing real physical and political challenges. His willingness to serve as Vice President after losing his gubernatorial race demonstrates the resilience and dedication that characterized many of the revolutionary generation.

Perhaps most importantly, Gerry’s life reminds us that the American experiment required not just visionary leaders but also practical politicians willing to do the unglamorous work of governance. From ensuring supplies reached freezing soldiers to presiding over a fractious Senate during an unpopular war, Gerry exemplified the commitment to public service that democracy demands. His statement that every citizen should devote even their last day to their country’s good captures the spirit of civic duty that animated the founding generation. While gerrymandering remains his most famous legacy, Elbridge Gerry deserves to be remembered as a dedicated public servant who helped transform revolutionary ideals into the practical machinery of government.

Thanks for reading!