T.L.D.R. –

- Age at Signing: 50

- Occupation: Surveyor/Lawyer

- Key Perspective/Position: “Poor man’s counselor”

- Personal Sacrifice: Two sons imprisoned on British ship

- Unique Contribution: Advocated for Bill of Rights

Read about the lives of the other signers of the Declaration of Independence here – ‘Who Were The Signers Of The Declaration Of Independence?’

Introduction

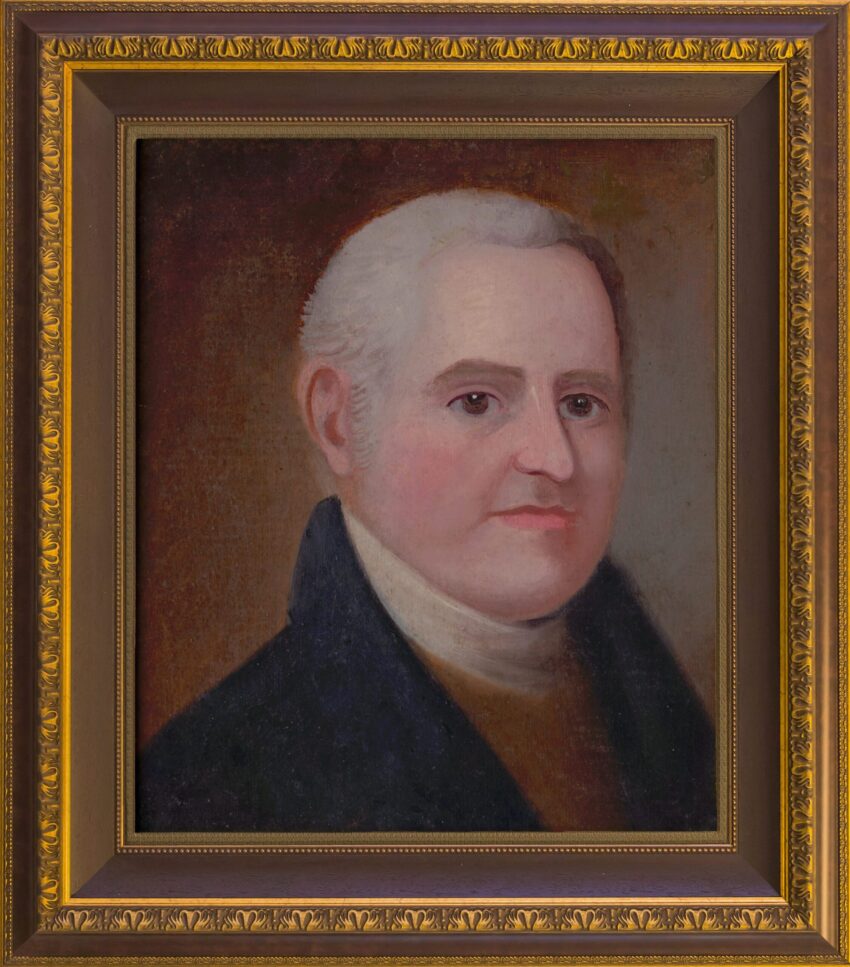

Abraham Clark was born on February 15, 1726, in present-day Elizabeth, New Jersey. With little formal education and chronic illnesses preventing farm work, he pursued independent study and developed strong mathematical skills. Known as a “poor man’s counselor,” he offered legal advice often for free, despite likely never being formally admitted to the bar. He married Sarah Hatfield, and they had ten children.

Clark began his public career as high sheriff of Essex County before joining the New Jersey colonial legislature in 1775. When New Jersey’s original delegates opposed independence, the state convention replaced them with six new delegates, including Clark. He served in the Continental Congress intermittently and often simultaneously in the state legislature. During the war, two of his sons were captured and imprisoned aboard the British prison ship Jersey.

After the war, Clark attended the Annapolis Convention of 1786 addressing the Articles of Confederation’s weaknesses. Though illness prevented his attendance at the Constitutional Convention, he lobbied for a Bill of Rights. He was elected to the Second and Third U.S. Congresses, dying of heat stroke on September 15, 1794, at age 68.

Contribution to Independence: Clark represented the common man’s perspective in Congress while his sons’ imprisonment demonstrated the personal costs of his political stance. His later advocacy for the Bill of Rights showed continued commitment to protecting liberty.

A Brief Biography

In the early hours of July 4, 1776, Abraham Clark wrote his friend Elias Dayton, the Colonel of a battalion of Jersey troops at German Flatts, from his lodging in Philadelphia.

. . . Our Congress Resolved to Declare the United Colonies Free and Independent States. A Declaration for this purpose, I expect, will this day pass Congress, it is nearly gone through, after which it will be Proclaimed with all the State & Solemnity Circumstances will admit. It is gone so far that we must now be a free independent State, or a Conquered Country. . . . This seems now to be a trying season, but that indulgent Father who hath

hitherto Preserved us will I trust appear for our help, and prevent our being Crushed; If otherwise, his Will be done.

Ten days later Clark wrote again to Dayton stating:

Our Declaration of Independence I dare say you have seen. A few weeks will probably determine our fate. Perfect freedom, or Absolute Slavery. To some of us freedom or a halter. Our fates are in the hands of An Almighty God, to whom I can with pleasure confide my own; he can save us, or destroy us; his Councils are fixed and cannot be disappointed, and all his designs will be Accomplished.

Clark was well aware, as were his fellow congressional delegates, of the gravity of the decision for independence from Great Britain as stated in an August 6th correspondence to the same friend, “Perhaps our Congress will be Exalted on a high Gallows.” Of the signers, Clark was a long-time public servant who held dear the concerns of the common man and the less fortunate. Clark historian, Ruth Bogin stated “Clark emerges as a champion of individual liberties, an enemy to every form of privilege, and a protagonist of government concern for the lowlier segments of the people.” One of five New Jersey delegates to the Continental Congress, Clark was prepared to risk everything he held dear for freedom from British tyranny.

Abraham Clark was born in Elizabethtown, New Jersey on February 15, 1726 the only child of Thomas Clark (born 1701) and Hannah Winans, who married about 1724. The signer’s paternal grandparents were Elizabethtown residents, Thomas Clark (born 1670) and Margaret Duehurst, who married in 1692. Abraham’s great-grandparents, Richard Clark (1613-1697) and wife Elizabeth also lived in Elizabethtown. Richard emigrated from England to Barbados in 1634 where he resided until 1651 when he moved to Southampton, Long Island. In 1657, Richard Clark fought in the Indian War. By 1667, Richard and Elizabeth settled in Southold, Long Island, where he was a shipbuilder and planter. About 1675 the family moved to Elizabethtown where the Clark name became synonymous with public service.

Abraham’s mother, Hannah, came from a family long in residence in the Elizabethtown area. Hannah’s parents were Samuel Winans, Sr. (1670-1747) and Zerviah (1684-1737). Abraham’s maternal great-grandparents John Winans (1640-1694) and Susanna Melyn (1645- c. 1688) married in New Haven, Connecticut, in August of 1664. John Winans, who emigrated from Holland, was one of the eighty associates that founded Elizabethtown in 1664. Over one-hundred-fifty Winans family members are buried in the cemetery adjacent to the First Presbyterian Church in present day Elizabeth, New Jersey, where the Clark and Winans families worshiped.

Susanna Melyn, the signer’s maternal great-grandmother, was the daughter of another Holland immigrant, Cornelius Melyn (1600-1662) who married Jannetje Adriaens (1604-1681) in Amsterdam in 1627. Melyn first arrived in New Netherlands in 1638 but soon returned to bring his family to the colonies “with an order granting him most of Staten Island” stated biographer Della Gray Barthelmas. Later Melyn moved to New Amsterdam where he became the President of the Council of Eight, but returned to Staten Island in 1649. On February 7, 1657 Cornelius Melyn “took the oath of fidelity with twenty-nine others” when he settled in New Haven, Connecticut.

Abraham Clark married Sarah Hatfield (sometimes spelled Hetfield) in 1748. It is said that Sarah was an intrepid and resourceful woman whose industry allowed her husband the opportunity for decades of public service. Sarah was the eldest daughter of Isaac Hatfield and Sarah Price (1728-1804). A notable cousin of Sarah’s was Mrs. Robert Ogden who was the mother of General Mathias Ogden and Aaron Ogden, who would later become Governor of New Jersey. The Hatfield family were said to be a well-to-do and respectable family of Essex County, New Jersey. Another cousin of Sarah Hatfield Clark was the First Presbyterian Church trustee and patriot Cornelius Hatfield. His son, Cornelius Jr., sided with the Tory’s during the Revolution. The junior Hatfield reportedly led the British to his father’s church in Elizabethtown on January 25, 1780 where they burned the fiercely patriotic congregation’s church to the ground. The elder Hatfield offered the congregants the use of his barn until 1787 as a meeting place following the incident. The church was rebuilt and remains in operation today as a Presbyterian Church.

During the Revolution the Rev. James Caldwell was the pastor of the First Presbyterian Church in Elizabethtown. Both he and his wife, with whom the Clark’s were close friends, were assassinated by the British in two separate incidents during the Revolutionary conflict. On August 2, 1776 which was the day most of the signers affixed their signatures to the Declaration of Independence, Clark wrote to Caldwell, who was also serving as the Chaplain of the Army at Ft. Stanwix at the time, of his successful motion that the Continental Congress should appoint a Congressional Chaplain stating: We have only to rely upon the Almighty, but that reliance is scarcely to be seen. At my coming to Congress, I moved for a Chaplain to Attend Prayers every morning which was carried-and some of my Starch brethren will scarcely forgive me for Naming Mr. [Jacob] Duche. This I did knowing without such a one many would not Attend. He hath Composed a form of Prayer Unexceptionable to all parties.

Abraham and Sarah had ten children during their marriage. Aaron Clark (1750-1811) was the eldest and served as a Second Lieutenant and Captain during the Revolution. Aaron married Susanna Winans, daughter of Captain Benjamin Winans in 1775 and after the Revolution moved to Washington, Pennsylvania, in 1790. The couple bore seven children, five born in New Jersey and two in Pennsylvania. His brother, Thomas (c. 1755-1789) also served as a First Lieutenant and Captain during the Revolution and is thought to be one of the two Clark sons who the British incarcerated on the Jersey prison ship. It is reported that Thomas was confined to the dungeon and the only food given him was pressed through the keyhole of the cell. His health suffered tremendously which accounted for his early death. Both Aaron and Thomas served in the Eastern Company, New Jersey state artillery under Captain Daniel Neil in Colonel Henry Knox’s Regiment Continental Artillery and State Battery. The company fought at the battles of Trenton and Princeton. Sources state that a cannon ball fired by the Neil artillery regiment is still lodged in the wall of Nassau Hall at Princeton University.

The third son, Abraham, born about 1755 died as a youngster in 1758. Hannah (born c. 1757), the eldest daughter, married Captain Melyn Miller, and fourth son Andrew (born 1759) died unmarried prior to 1794. Sarah was born in 1761 and later married General Clarkson Edgar. Cavilier Clark (born c. 1763) died in infancy a year after his birth. Elizabeth (born c. 1765) died from smallpox during the epidemic that spread across the revolutionary landscape in 1776. A fifth son named Abraham (born 1767), after his father and deceased brother, became a physician and married Lydia Griffith. The youngest child Abigail born in 1773 married Thomas Salter. Many of Abraham Clark’s children died childless or their offspring remained childless. At this writing verified descendants have been proven through Aaron, the eldest son’s line, and it is said through the second son Thomas, although verifiable documentation remains elusive.

As seen above the Clarks and their relatives had long been Elizabethtown residents on the eve of the Revolution. Located in north New Jersey, Elizabethtown (now Elizabeth) sits directly across the channel from Staten Island and New York City. When England claimed the area from the Dutch in 1664 there were only 200 inhabitants. By 1776 the locality boasted a population of 125,000 and was, as Mark Di Ionno states the “commercial and cultural center” and leading “social and intellectual city in New Jersey.” New Jersey was the only colony that housed two colleges, Princeton and Rutgers. Princeton University was founded by the same First Presbyterian Church where the Clark family attended. The school was first called the College of New Jersey before moving to Princeton. The Old Academy building still remains on the church property and is marked by a small plaque. Notable students who attended at the location are Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton. The Clark property was situated about three to four miles from the Staten Island channel and comprised approximately three hundred acres. Because of Elizabethtown and New Jersey’s location during the Revolution, over one hundred battles and skirmishes occurred on its soil. The Clark property was destroyed, although the house remained safe during the conflict.

Abraham Clark served the Crown for years before independence. From 1752-1766 Clark served as clerk of the New Jersey colonial legislature and became the high sheriff of Essex County. He was a man too frail for agrarian pursuits, but his bent toward math and civil law served him well, though very little of his schooling was considered formal. Clark’s occupation was that of surveying and preparation of deeds, mortgages, and other legal papers. Several historians, including Charles A. Goodrich, stated Clark earned the reputation as “the poor man’s counselor” because of his refusal to accept payment for legal advice. On the subject of law, he was self-taught and most likely was never admitted to the bar. On the road to independence Clark served on the New Jersey Committee of Safety, for which he was secretary. Signer, John Hart also served with Clark on the Committee of Safety in New Jersey.

Clark also served in the Provincial Congress of New Jersey who hand-picked a delegation of five to represent the colony at the Continental Congress which was already meeting in Philadelphia in June, 1776. The members of the Provincial Congress also chose John Hart, Rev. Dr. John Witherspoon (who delivered the opening prayer), Richard Stockton and Francis Hopkinson. Hart historian, Cleon E. Hammond stated Clark, Hart, and Witherspoon often shared lodgings whereas Clark commented in an August 7, 1776 letter from Philadelphia that the three of them “quarter together, and endeavor to make our lives as agreeable as possible.” The men were in Philadelphia, of course, for the formal signing of the Declaration of Independence that occurred on August 2. Clark historian and relative, Rev. Dr. Edwin F. Hatfield, pointed to the relationship with Witherspoon stating “Mr. Clark was a man of prayer and was quartered at Philadelphia, with his colleague, the Rev. Dr. Witherspoon. Both these worthy men had acted throughout on Christian principle and with a deep sense of their responsibility to Almighty God.”

After the execution of the Declaration, Clark’s public service continued until the end of his life. From Philadelphia on July 5, 1776, Clark wrote William Livingston, a former New Jersey delegate who had recently been chosen second Brigadier General of the New Jersey militia. In Clark’s letter to Livingston he stated, “I enclosed a Declaration of Congress, which is directed to be Published in all the Colonies, and Armies, and which I make no doubt you will Publish in your Brigade.” Throughout the war Clark raised supplies for Washington’s army, meanwhile nearly always present in Congress to vote. Many of the remaining Clark letters discuss troop movements and procurement.

Clark was one of only twelve men including Alexander Hamilton, John Dickinson, Edmund Randolph, and James Madison Jr., who attended the Annapolis Convention of 1786 to discuss remedies to the federal government. As early as August 1, 1776 Clark was concerned about the debates underway surrounding the country’s first constitution when he penned the following remarks to Rev. Caldwell:

. . . Our Congress have now under Consideration a Confederation of the States. Two Articles give great trouble, the one for fixing the Quotas of the States towards the Public expense and the other whether Each state shall have a Single Vote or in proportion to the Sums they raise or the num[be]r of Inhabitants they contain. I assure you the difficulties attending these Points at Times appear very Alarming. Nothing but the Present danger will ever make us all Agree, and I sometimes even fear that will be insufficient.

Clark was elected to the Constitutional Convention of 1787 (for which he was too ill to attend), to the House of Representatives for the second and third U.S. Congress from 1791-1794, and served as trustee of the First Presbyterian Church. Following the Revolution, Clark served as a commissioner to settle New Jersey’s accounts with the federal government. Dennis B. Fradin stated it was upon Clark’s insistence the word “Liberty” was placed on the U.S. coinage.

In 1784, The New Jersey legislature, of which Clark remained a member, passed “Clark’s Law” which was “An Act for Regulation and Shortening the Proceeding of the Courts of Law.” Bogin quoted Clark that, “If it succeeds, it will tear off the ruffles from the lawyer’s wrists” a nod to his disdain for pretense. In February, 1786 the Jersey legislature passed a bill sponsored by Clark for “An Act to prevent the Importation of Slaves . . . and to authorize the Manumission of them under certain Restrictions and to prevent the Abuse of Slaves.” Even though Clark owned three slaves, and did not provide for their release until both he and Sarah died, this act was an important recognition by the legislature and Clark, as Bogin noted, that “slavery involved ethical considerations.” In 1794, Clark introduced a resolution in the U.S. House “to suspend all relations with England until all articles of the Treaty of Paris were executed” as reported by Barthelmas. The measure passed the House and was narrowly defeated by the Senate with the tie-breaking vote of John Adams.

According to Fradin “Abraham Clark may have been the signer who was closest to being a typical citizen.” As seen above he hated pretense and elitism and never wore a wig or the ruffles of high social standing. Clark was very popular among the poor in New Jersey. Contemporaries commented that Clark was “limited in his circumstances, moderate in his desires, and unambitious of wealth” and “very temperate” as noted by Hatfield. According to historian, Edward C. Quinn, Clark “. . . regarded honesty, thrift, and independence as cardinal public virtues.” He loved to study and imbued a generous character. Clark was particularly admired for his punctuality, integrity, and perseverance.

Clark described himself as a Whig, and demonstrated throughout his life and in public service to be a champion of the people’s liberties. Bogin stated “One difference between Clark and many other Whigs [was he understood] . . . tyranny might arise from the new American centers of power as well as from the British . . . . Clark “did not believe men in public office should use their positions to confer favors on members of their personal families” according to Quinn. When his two sons were prisoners of war on the Jersey, he refused to reveal the issue to Congressional delegates. Only when members found out about the treatment of Thomas Clark in the Jersey dungeon did intervention occur. When Congress threatened retaliatory measures on a British officer Clark’s son was released from the dungeon, but neither son escaped the Jersey until the general exchange of prisoners. The British offered to release Clark’s sons if he defected to the Tory side, but he refused.

Perhaps Clark’s obituary (reproduced here in the original English vernacular of the period) that appeared on Wednesday, September 17, 1794 in The New-Jersey Journal best exemplifies the contemporary view and character of Abraham Clark:

[Deaths] On Monday last, very suddenly, the Hon. Abraham

Clark, Esq. member from this State, to the Congress of the United

States, in the 69th year of his age. In the death of Mr. Clark, his

Family has sustained an irretrievable loss, and the state is deprived

of a useful citizen, who, for forty years past, has been employed in

the most honorable and confidential trusts, which he ever dif-

charged with that disinterestedness, ability, and indefatigable

industry, that redounded much to his popularity; indeed it may

be said of him, that he was a person from his youth, with whom

the amor patriae pieponderated every other consideration. It

could not be expected that such a character would pass unnoticed

by the jaundiced eye of envy and faction, which was really the

café with the deceased, but his conduct was so unequivocally

upright, that the unvenomed shafts of envy could never remove

him from the confidence of the people, or shake his popularity.

Mr. Clark was a man of sound judgment, lively wit, and very

satyrical; in the exercise of which he made sometimes enemies.—

As a Christian., he was uniform and consistent, adorning that

religion, that he had early made a profession of, by acts of charity

and benevolence.

Abraham Clark died on September 15, 1794 approximately two hours after suffering a sun stroke, having observed the construction of a bridge on his property. It is said that he may have survived the event had not he taken time to drive his cousin home first. But to have considered his own well-being before that of others would have been out of character for the man described above. Clark was a Christian, family man, patriot, public servant, and a gentleman. The men who pledged their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor to break free from British tyranny faced untold dangers, as Clark related to his beloved friend Elias Dayton on July 4, 1776:

. . .We are now Sir embarked on a most Tempestious Sea,

Life very uncertain, Seeming dangers Scattered thick

Around us, Plots Against the Military, and it is Whispered,

Against the Senate. Let us prepare for the worst, we can

Die here but once. May al[l] our Business, all our purposes

& pursuits tend to fit us for that important event. . . .

In an August letter to Dayton during the momentous summer of 1776, Abraham Clark proclaimed what most of the founders understood when they signed the Declaration of Independence that “Nothing short of the Almighty Power of God can save us.”

Biography credit here.

Final Thoughts

Looking at Abraham Clark’s life and service, what strikes me most is how he embodied the revolutionary spirit of ordinary Americans who risked everything for independence. Unlike many of his fellow signers who came from wealth and privilege, Clark was “the poor man’s counselor” who often worked without payment, wore no wigs or ruffles, and maintained a deep connection to the common people of New Jersey. His willingness to sign the Declaration while fully aware that it might lead to “a high Gallows” demonstrates the profound courage required of these founders. The fact that two of his sons were imprisoned on the notorious British prison ship Jersey, with one confined to a dungeon and fed through a keyhole, makes his sacrifice deeply personal and tangible.

Clark’s contributions extended far beyond that pivotal moment in 1776. His tireless advocacy for individual liberties and opposition to privilege shaped both New Jersey and the nation. From his early work reforming legal procedures to make courts more accessible, to his groundbreaking legislation restricting slavery in 1786, Clark consistently championed the rights of the vulnerable. His insistence that the word “Liberty” appear on U.S. coinage and his later push for a Bill of Rights reveal a man who understood that independence was merely the first step—true freedom required constant vigilance against tyranny, whether from foreign powers or domestic elites. His refusal to use his position to secure his sons’ release from British captivity exemplifies the integrity he brought to public service.

In Abraham Clark, we see the best of the American founding: a self-educated surveyor who rose through merit rather than birth, a devoted family man who nevertheless spent decades in public service, and a Christian whose faith informed his commitment to justice and liberty. His death in 1794—occurring because he prioritized driving his cousin home over seeking immediate medical attention after suffering sunstroke—perfectly captures his character. As his obituary noted, for forty years he served with “disinterestedness, ability, and indefatigable industry,” driven by an amor patriae (love of country) that “preponderated every other consideration.” In our current era of political cynicism, Clark’s example reminds us that authentic public service, grounded in principle and sacrifice, helped birth this nation and remains essential to its survival.

Thanks for reading!