T.L.D.R. –

- Age at Signing: 41

- Occupation: Land Speculator

- Key Perspective/Position: Early patriot despite NY hesitation

- Personal Sacrifice: Home became British barracks; wife died

- Unique Contribution: Fled to Connecticut

Read about the lives of the other signers of the Declaration of Independence here – ‘Who Were The Signers Of The Declaration Of Independence?’

Introduction

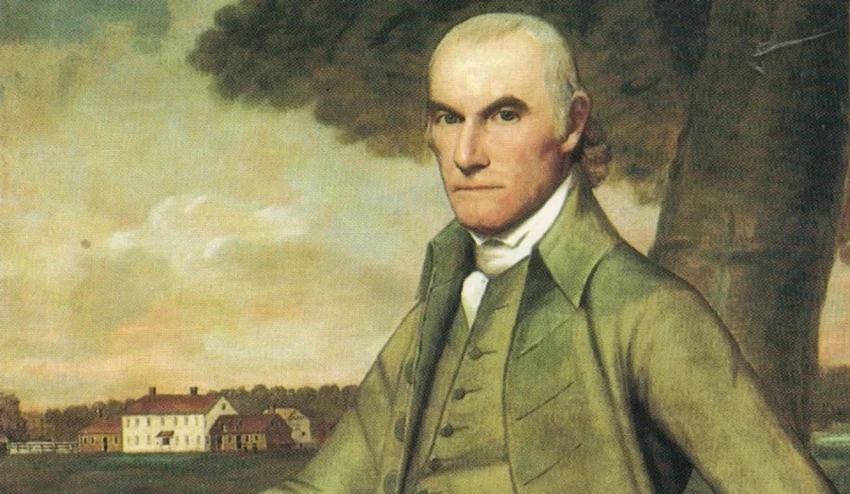

William Floyd was born on December 17, 1734, on Long Island, New York, the second of nine children. His father was a successful Welsh farmer who instilled a strong work ethic. When his parents died in 1755, Floyd inherited the family estate and took responsibility for his siblings. He married Hannah Jones in 1760, and they had three children.

Floyd became a respected community figure and militia leader, attaining the rank of Colonel in 1775. He supported the Patriot cause early, attending meetings opposing the British closure of Boston’s port. In 1774, he was chosen to represent Suffolk County in the Continental Congress, serving until 1777 and again from 1779-1783. He also held the rank of Major General in the militia.

During the war, the British occupied Floyd’s home, converting it into barracks. His family fled to Connecticut, where his wife died in 1781 after prolonged illness. After the war, Floyd served in the New York State Senate, the First U.S. Congress (1789-1791), and was a presidential elector four times. He invested in land in central New York, eventually relocating there and dying on August 4, 1821, at age 86.

Contribution to Independence: Floyd signed the Declaration knowing the personal cost—his estate was destroyed and his family displaced. His commitment to independence despite these hardships exemplified the signers’ pledge of “lives, fortunes, and sacred honor.”

A Brief Biography

William Floyd was the eldest child of a prosperous Long Island family of Welsh descent. His great grandfather, Richard Floyd had emigrated from Wales to Long Island in the 17th C. William’s parents were Nicoll Floyd and Tabitha Smith. Young William was born on 17 December 1734 in what is now called Mastic, Long Island, but was then a part of Brookhaven Township. William’s father, Nicoll, died when the young man was only 17 years old, leaving him a large estate. He managed it well, learning how to make profits from both the tenants on the property and the produce and animals grown on it. He was an excellent farmer and manager.

His early education had been a practical one, not a formal scholarly one. As a wealthy landowner, Floyd acquired stature and influence in his community. The manor house, being the resort of an extensive circle of connections and acquaintances, including many persons from distinguished families with excellent formal educations, Floyd absorbed much knowledge. He had a fine writing hand, as evidenced by his signatures; and his understanding of land measurements and accounts had to be good to manage the estate. The property was highly productive, with grains, forage, vegetables; and well stocked with cattle and fruit trees. Fronting on the Atlantic Ocean, Floyd also had a shipping dock used for trade, and access to fishing, oysters, and a variety of seafood. His accounts tell us that he dealt widely with carpenters, brick masons, farriers, butchers, and a variety of trades people.

William Floyd married Hannah Jones [or Johnes], daughter of William Jones of Southampton, LI, NY at Brookhaven, LI, NY on 23 August 1760. They had three children; a son, Nicoll, and two daughters, Mary, and Catherine, all of whom married and had issue. As the “Old French War” came to an end with the Treaty of Paris on 10 February 1763, and the succeeding years augured ill for good relationships with England and the confining enactments of Parliament, Floyd, with his excellent connections, became increasingly prominent in the politics of eastern Long Island. Like so many of his neighbors Floyd had strong ties to Connecticut. It was easier to reach that neighboring colony across Long Island Sound than it was to travel overland into New York City. Floyd’s father had lent money to Connecticut Governor Jonathan Trumbull and the Floyd family had relatives and friends in Middletown.

In addition to his growing political connections in eastern Long Island, Floyd was no doubt also influenced by the attitudes of his Connecticut friends and relatives. He was active in the town affairs of the town of Brookhaven. He was three times elected a trustee of the town and served as an officer in the local militia. In 1769 he was elected to the Provincial Assembly. This permitted him to become acquainted with political figures from other parts of the Colony. As a result, when Suffolk County chose delegates to the First Continental Congress in 1774, Floyd was an obvious selection.

By early 1775 the issues between the colonies and the mother country had warmed considerably and resulted in the Battle of Lexington/Concord on 19 April. The colony of New York elected ten men to attend the Second Continental Congress but because of other commitments either local or Colony only four of them, including William Floyd attended and presented their credentials. He probably arrived in Philadelphia on 10 May 1775. He soon found himself on several committees and spent part of his time on inspection tours, visits, and meeting with other delegations.

On 5 September 1775 William Floyd was nominated Colonel of the Western Regiment of Suffolk County at a meeting in Smithtown. Taking over and inspecting this new command Floyd reports, “The Regiment is about two-thirds furnished with bayonets, and the others are getting them as fast as they can be made. They are furnished with half pound of powder and two pound of ball per man and a Magazine in the Regiment to furnish them …” Floyd shared his time between his military duties and his Congressional duties. As a delegate to the Continental Congress, he kept the New York Provincial Congress informed about actions such as reconciliation with Great Britain, the treatment of Loyalists, Indian Affairs, establishment of local military defense, aid to the Continental Army, the issuance of paper money, and other matters that the local colony assembly needed to know about or act upon. Floyd’s time in the Continental Congress was steadfast and supportive although he seldom spoke. Edmund Rutledge, a Delegate from South Carolina said of Floyd, that he was among the “good men who never quit their chairs,” implying that Floyd seldom spoke on the floor, but was frequently present and voting for issues.

As Washington tightened the noose around Boston and used the cannon Knox had brought from Fort Ticonderoga, so that the British finally evacuated the city and Washington prepared for a descent upon New York, the Congress was arguing the merits of “Independency”. New York had not instructed its delegation to vote for any such matter as independence, so Floyd, and his fellow New York delegates had their hands tied until the New York Provincial Congress would come to some conclusion. While the Continental Congress voted for Richard Henry Lee’s resolution regarding independence on 2 July 1776 and then spent two days adjusting the language in the committee’s declaration of the matter, the New York delegation had to remain silent. Finally, on 9 July 1776 the New York provincial Congress voted to approve independence and forwarded that information to their delegation in Philadelphia which arrived on 11 July 1776. So now we have a “Unanimous declaration”! Although independence had been approved and the language of the document supporting it had been modified and approved, it was not until 1 August 1776 that most of the delegates were able to sign an embossed copy of the Declaration of Independence, among whom was William Floyd.

Hardly was the ink dry from the Deletes signing of the Declaration, when the British landed on Long Island and defeated Washington in a battle there on 27 August 1776. The British, within the next three months, overran the entire Island of Long Island including Floyd’s home at Mastic. Mrs. Floyd had time to bury the family silver before she and her three children, with a few friends and neighbors fled across the waist of the island to its north shore and sailed across Long Island Sound to shelter with friends in Middletown. On 17 October 1776 William Floyd reported, “I am now going to try to get some of my effects from the island if it is possible, and shall be absent from Congress a few days, I beg you would excuse me as it is the first time, I have absented myself.” On 28 October 1776 Governor Jonathan Trumbull ordered an armed party to cross the Sound and bring back Floyd’s possessions.

William Floyd continued to faithfully serve both his military obligations, for which he was eventually raised in the militia to Major General, and to his duty as a delegate to the Continental Congress. He was a member of the Clothing Committee and served additionally on several other committees from time to time. He served a short term in the New York State Senate but in January 1779 was sent back to the Continental Congress. His wife, Hannah (Jones) Floyd died on 16 May 1781 as a result of exposure, fatigue, stress, and illness. Floyd returned to his Long Island estate at the end of the war in 1783 to find ransacked buildings, desolate fields, uprooted trees, burned fences, lost stock, and his house unlivable. On 16 May 1784 he married, as his second wife, Joanna Strong, daughter of Benjah and Martha (Mills) Strong. She was born in Setauket, New York on 4 January 1747. By her he had two additional children, Anna Floyd, and Eliza Floyd, both of whom married and had issue.

By 1794 Floyd conveyed his Long Island estate to his son Nicoll and moved to a large tract of land in Oneida County then in the frontier area of New York State at what is now Westernville, and built himself a new home there, almost a copy of his old estate at Mastic. There he resided for several years in retirement and died on 4 August 1821 and is buried in the Presbyterian cemetery there. His 2nd wife, Joanna died there on 24 November 1826.

Biography credit here.

Final Thoughts

William Floyd’s story embodies the profound personal sacrifices made by those who signed the Declaration of Independence. While many signers faced financial hardship or political persecution, Floyd’s losses were particularly devastating—his family was forced to flee their home, his wife died in exile from the hardships of displacement, and his prosperous Long Island estate was utterly destroyed by British occupation. Yet he never wavered in his commitment to independence, continuing to serve in both military and civilian capacities throughout the war. His willingness to risk everything he had built demonstrated that the pledge of “lives, fortunes, and sacred honor” was not mere rhetoric but a solemn covenant these men truly upheld.

Floyd’s career also illustrates the interconnected nature of colonial resistance and the importance of regional networks in building the revolutionary movement. His connections to Connecticut, facilitated by geography and family ties, likely influenced his early support for the patriot cause at a time when New York remained hesitant about independence. His dual service in the Continental Congress and the Suffolk County militia exemplifies how the Revolution required leaders to operate at multiple levels simultaneously—maintaining local defense while participating in the broader continental struggle. Though he was noted as one who “never quit their chairs” rather than a fiery orator, Floyd’s consistent presence and steady support provided the reliable foundation upon which more dramatic revolutionary actions could be built.

The trajectory of Floyd’s life—from prosperous Long Island landowner to war refugee to frontier settler—mirrors the transformation of America itself during this period. His decision to start anew in the wilderness of upstate New York after the war, rather than simply rebuilding his old life, reflects the pioneering spirit that would define the new nation. That he lived to age 86, surviving to see the young republic mature through its first decades, allowed him to witness the fruits of his sacrifice. William Floyd’s legacy reminds us that independence was won not just by famous generals and eloquent statesmen, but by steadfast citizens willing to endure profound personal loss for the principle of self-governance.

Thanks for reading!