T.L.D.R. –

- Age at Signing: 69

- Occupation: Merchant

- Key Perspective/Position: “Hand trembles, heart does not”

- Personal Sacrifice: Palsy; second oldest signer

- Unique Contribution: Helped shield Gaspee Affair patriots

Introduction

Stephen Hopkins was born on March 7, 1707, in Providence, Rhode Island. Though self-educated, he taught himself surveying and practical sciences, beginning public service at 23 as a justice of the peace. He became a successful merchant with significant land holdings and married twice, having seven children.

Hopkins rose through colonial government ranks, becoming Chief Justice of the Rhode Island Supreme Court by 1751. As colonial governor, he supported British efforts during the French and Indian War while taking progressive positions like advocating to ban slave importation into Rhode Island. He played a central role in the 1772 Gaspee Affair aftermath, helping ensure no colonists were indicted for burning the British naval ship.

A vocal critic of British overreach, Hopkins was chosen as a Rhode Island delegate to the Continental Congress. Despite suffering from palsy at age 69, he signed the Declaration, declaring, “My hand trembles, but my heart does not.” He was forced to resign from Congress in 1776 due to health problems but was elected to the Rhode Island state legislature upon his return. He died on July 13, 1785, at age 78.

Contribution to Independence: As the second-oldest signer after Benjamin Franklin, Hopkins brought gravitas and experience to the independence movement. His shaking signature on the Declaration became a symbol of unwavering commitment despite physical frailty.

A Brief Biography

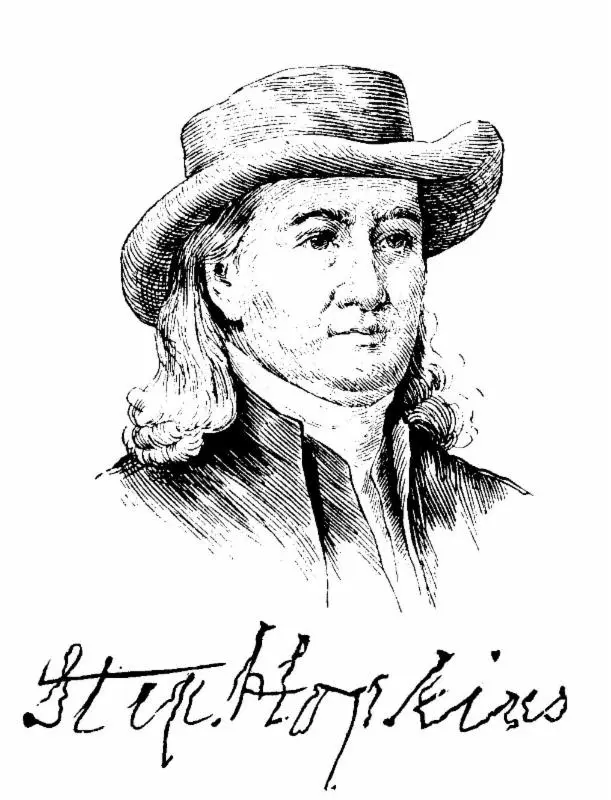

Stephen Hopkins’ name is not one of the first names that comes to mind as a signer of the Declaration of Independence, but he does stand out in John Trumbull’s painting “The Declaration of Independence.” Hopkins is clearly visible in the rear, wearing a hat. He also stood out as an exceptional man, a colonial governor, educator, judge, merchant ship owner, surveyor, and patriot.

Stephen Hopkins was born on March 7, 1707 in Providence, Rhode Island, the son of William Hopkins and Ruth (Wilkinson) Hopkins. Hopkins’ great grandfather, Thomas Hopkins, was born in 1616 and came to Providence in 1641, having followed Roger Williams there from Plymouth. In 1651 he moved to Newport and was appointed a member of the town committee in 1661.

His mother, Ruth Wilkinson, was the granddaughter of Lawrence Wilkinson, a lieutenant in the army of Charles I, who was taken prisoner October 22, 1644 by the Scots and parliamentary troops at the surrender of Newcastle-on-Tyne. Deprived of his property, he came to New England sometime between 1645 and 1647 and was at Providence in 1652. He became a freeman in 1658, was chosen deputy to the General Court, was a soldier in the Indian wars, and became a member of the Colonial Assembly in 1659.

Stephen Hopkins was a cousin of Benedict Arnold, the famous Revolutionary War General who later turned traitor.

Hopkins grew up on a farm in Scituate, Rhode Island. He had little formal education and his mother taught him his first lessons. His grandfather and uncle instructed him in elementary mathematics, and he read the English classics in his grandfather’s small but well-selected library.

Hopkins married Sarah Scott on October 9, 1726, when they were both just 19, and they had five sons and two daughters. Sarah was the youngest daughter of Major Sylvanus Scott and Joanna Jenks. Her great grandfather, Richard Scott of Glensford, County Suffolk in England, was admitted to the church at Boston in 1634, but removed to Providence where he became the first Quaker preacher at Providence. He married Catharine Marbury, a niece of Anne Hutchinson who was banished from Massachusetts Bay for preaching the grace of God.

Sarah’s mother, Joanna Jenks, was the daughter of Joseph Jenekes (Jenks) who at the age of two came to America in the James in 1635, with his father, also named Joseph Jenks. They came from Bucks County in England and the elder Jenks established the iron works at Lynn, MA. Jenks also cut the dies for the “Pine Tree Shilling” in 1652, built the first colonial fire engine in 1654 and invented the grass scythe.

Hopkins earned the trust of his fellow citizens and quickly became prominent in local affairs. He became a surveyor and at the age of 24 was selected to moderate the first town meeting held in Scituate. In 1732 he became town clerk, and was president of the Town Council in 1735. He represented Scituate frequently in the General Assembly from 1732 to 1741, and was named Speaker there in 1742.

About 1740 he joined his brother Esek Hopkins in commercial ventures and established his permanent residence at Providence in 1742. The two brothers established a mercantile-shipping firm and were actively involved in building and fitting out vessels. Stephen served in the General Assembly from 1744 to 1751, was assistant justice of the Rhode Island Superior Court from 1747 to 1749, and became Chief Justice in 1751.

Hopkins was largely responsible for transforming Providence from a small village with muddy streets to a thriving commercial center. He was also instrumental in establishing Rhode Island’s present-day boundaries. Besides his political and civic interest, Hopkins had interest in education and science. About 1754 he was influential in establishing a public subscription library, and he was the first chancellor of Rhode Island College, which was to become Brown University. He helped found the Providence Gazette and Country Journal in 1762, held membership in the American Philosophical Society of Newport, and was involved in erecting a telescope in Providence for observing the transit of Venus, which occurred in June 1769.

Stephen Hopkins won the governorship of Rhode Island in 1755, and was governor several times through 1766, competing with Samuel Ward for the annual election for the governorship. Hopkins attended the Albany Congress of 1754 where he first met Benjamin Franklin, who promoted the Albany Plan for uniting the colonies. The plan failed, but Stephen and Benjamin became friends and were to become the two most elderly signers of the Declaration of Independence in 1776.

After the passage of the hated Stamp Act by Parliament, Hopkins wrote The Rights of Colonies Examined, published in 1764, a pamphlet in which he attacked the Sugar Act and the Stamp Act, stating: “British subjects are to be governed only agreeable to laws which they themselves have in some way consented.” It predated John Dickinson’s more widely distributed Letters from a Farmer by three years.

When John Hancock’s ship was seized by the British and sent to Newport, it was burned by an angry mob. Royal Governor Wanton received instructions to arrest those involved and to send them to England for trial. Hopkins, as chief justice, stated he would neither apprehend them nor suffer any executive officers to do so.

At a meeting of the General Assembly of Rhode Island in 1774, Hopkins introduced a bill to prevent further importation of slaves and freed those slaves which he owned.

Named as one of two Rhode Island residents to the First Continental Congress in 1774, Hopkins made a bold declaration concerning the resolution of the differences between the colonies and the British “…. powder and ball will decide this question. The gun and bayonet alone will finish the contest in which we are engaged, and any of you who cannot bring your minds to this mode of adjusting this question had better retire in time.”

Hopkins signed the Olive Branch Petition to the King in July, 1775, seeking a peaceful resolution of the colonies’ grievances. He arranged for his younger brother Esek Hopkins to become the first commander in chief of the Continental Navy.

During the intense debate over independence that began on July 1, 1776, Stephen Hopkins provided a moment of humor. As thunderstorms broke over Philadelphia, John Dickinson was well into his second hour of speaking against independence. Suddenly, Dickinson’s talk was interrupted by a vigorous thunderclap which rattled the building. Hopkins dropped the hickory cane his head had been resting on, and looked about sharply.

Sitting behind him, John Penn of North Carolina jumped up, fearful the old gentleman had been frightened. He leaned over Hopkins’ shoulder to whisper reassurance, telling him there was no reason to be alarmed. “There is a rod atop the State House,” he said, “—one of Dr. Franklin’s inventions—the celebrated lightning rod. If by chance a bolt of lightning should strike the belfry, that same rod would run the bolt into the ground.”

Turning to Penn, Hopkins roared, “I don’t give a damn about any rod or lightning bolt. I’m just tired of Dickinson’s long-winded harangue!”

Stephen Hopkins voted to approve the Declaration of Independence on July 4 and signed the engrossed copy on August 2. He suffered from the “shaking palsy” which caused his signature on the Declaration to appear unsteady, and he used his left hand to steady his right. He stated at the signing, “My hand trembles, but my heart does not.” Hopkins’ palsy affliction was of long standing, causing him to rely upon a clerk to write for him in his businesses and public life.

In June of the same year Hopkins was appointed to the 13-member committee (one from each state) to draft the country’s first constitution, The Articles of Confederation. His health failing, he returned to Rhode Island soon thereafter.

Hopkins died on July 13, 1785 and is buried in the North Burying Ground at Providence. An extensive cortege and assembly of notable persons followed the funeral procession of Hopkins to the cemetery, including court judges, the President, professors and students of the College, citizens of the town and inhabitants of the state. The Rhode Island legislature dedicated a special monument at his gravesite in his honor, and it provides an elaborate testimony to the life of the patriot.

On the west side the inscription says, “Sacred to the memory of the illustrious Stephen Hopkins, of revolutionary fame, attested by his signature to the Declaration of our National Independence, Great in Council from sagacity of mind; Magnanimous in sentiment, firm in purpose, and good, as great, from benevolence of heart; He stood in the front rank of statesmen and patriots. Self-educated, yet among the most learned of men; His vast treasury of useful knowledge, his great retentive and reflective powers, combined with his social nature, made him the most interesting of companions in private life.

On the south side the inscription continues: “His name is engraved on the immortal records of the Revolution, and can never die: His titles to that distinction are engraved on this monument, reared by the grateful admiration of his native state, in honor of her favorite son.”

And on the east side: “Hopkins, born March 7, 1707, Died July 13, 1785.”

And on the north side: “Here lies the man in fateful hour,

Who boldly stemm’d tyrannic pow’r,

And held his hand in the decree,

which bade America BE FREE!

–Arnold’s poems—

As a public speaker he was described as clear, precise, pertinent, and powerful. John Adams admired the elderly man for his long experience in public life and good judgment in chambers, saying “He read Greek, Roman, and British history….and the flow of his soul made his reading our own, and seemed to bring to recollection of all we had ever read.” Adams also enjoyed a more personal side of Hopkins. “His custom was to drink nothing all day, nor ‘til eight o’clock in the evening, and then his beverage was Jamaica spirits and water…. He kept us alive.”

Biography credit here.

Final Thoughts

Stephen Hopkins embodied the spirit of the American Revolution through both his words and actions. His famous declaration at the signing—”My hand trembles, but my heart does not”—captures the essence of the Revolutionary generation: ordinary men facing extraordinary circumstances with unwavering resolve. Despite his palsy and advanced age, Hopkins never wavered in his commitment to independence, serving as a powerful example that physical limitations need not constrain moral courage. His self-education and rise from surveyor to colonial governor demonstrated the meritocratic ideals that would become central to American identity.

Hopkins’ contributions extended far beyond his signature on the Declaration. As a progressive leader, he took bold stances that were ahead of his time, from advocating to ban slave importation to protecting colonists involved in the Gaspee Affair. His role in transforming Providence from a small village into a thriving commercial center, establishing educational institutions like Brown University, and fostering scientific advancement through projects like the Venus transit telescope showed his vision for what America could become—a nation of commerce, learning, and innovation. These achievements, combined with his political service spanning over five decades, made him an indispensable bridge between colonial governance and revolutionary ideals.

Perhaps most remarkably, Hopkins recognized early what many of his contemporaries could not yet see: that the conflict with Britain would ultimately be settled by force, not negotiation. His prescient 1774 declaration that “powder and ball will decide this question” proved tragically accurate, yet he still signed the Olive Branch Petition, demonstrating his preference for peace even while preparing for war. John Adams’ fond remembrance of Hopkins—how he “kept us alive” with his wit, wisdom, and evening toddy—reminds us that the Founders were not marble statues but flesh-and-blood individuals who faced their monumental task with both gravity and good humor. In Stephen Hopkins, we see the Revolution’s human face: learned yet humble, principled yet practical, trembling in body but steadfast in spirit.

Thanks for reading!