T.L.D.R. –

- Age at Signing: 41

- Occupation: Planter

- Key Perspective/Position: Quiet brother of Richard

- Personal Sacrifice: No children

- Unique Contribution: Behind-scenes consensus builder

Introduction

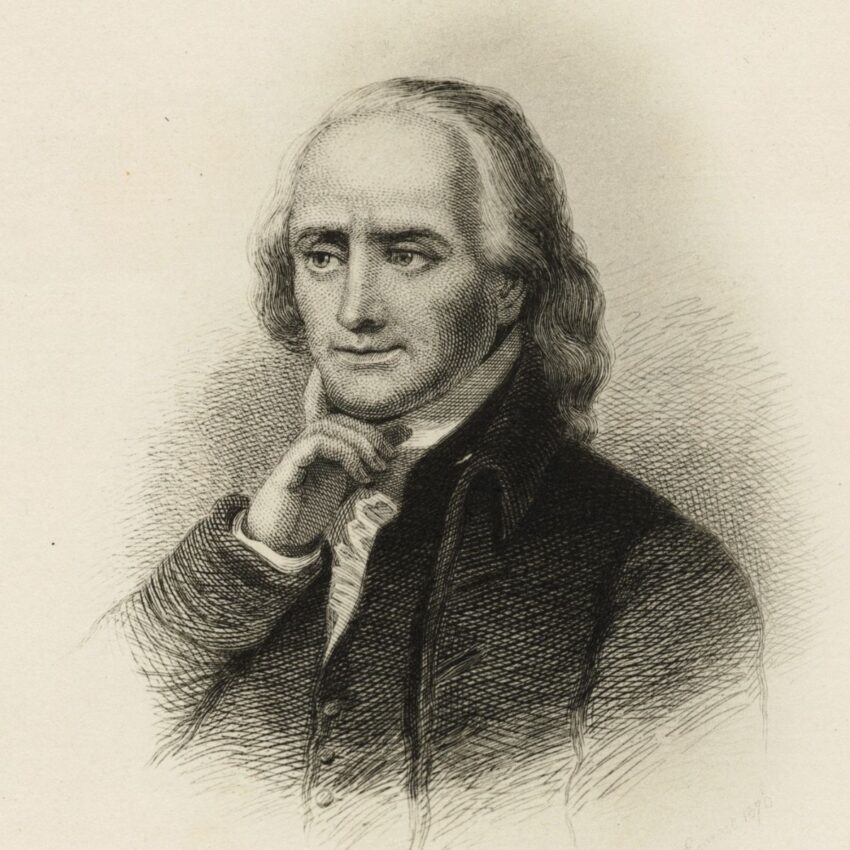

Francis Lightfoot Lee was born on October 14, 1734, at Stratford Hall Plantation, Virginia, into the prominent Lee family with American roots dating to the 1630s. Privately educated by tutors, he didn’t attend college but focused on managing family landholdings. He married Rebecca Tayloe in 1769, but they had no children.

By the late 1750s, Lee turned to politics, elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses where he opposed British policies like the Stamp Act. His dedication led to election to both Continental Congresses alongside his brother Richard Henry Lee. Though equally committed to independence, the brothers differed in style—Richard was known for public speaking while Francis led through quiet action.

In 1776, Francis Lightfoot Lee signed the Declaration and helped draft the Articles of Confederation. He briefly served in the Virginia State Senate before retiring to his estate, Menokin. He died on January 11, 1797, at age 62, just days after his wife Rebecca.

Contribution to Independence: Representing the quieter patriots, Francis Lightfoot Lee’s signature alongside his brother’s showed family unity in the cause. His behind-the-scenes work helped build consensus for independence.

A Brief Biography

A quiet philosopher, Francis Lightfoot Lee grew up at a large tobacco plantation and impressive home, Stratford Hall, in Virginia. He was a son of Thomas and Hannah Ludwell Lee with three older and two younger brothers and two sisters. Family and friends called him Frank. He had been named for his father’s best man, Francis Lightfoot of Charles City County, Va.

Francis’s great grandparents, Richard Lee, had arrived from England in 1639. Richard was the personal secretary of Virginia’s royal governor, Sir Francis Wyatt, and married ward Anne Constable. The Lees did very well selling furs, tobacco, and English-made goods through Lees on both sides of the Atlantic, collecting an enormous amount of land. The American Lees kept up the relationship with their British cousins for many generations.

When a young teenager, Francis watched his older brothers sail for England in Lee tobacco ships for their education. Perhaps he thought it would be his turn next when he was a little older, but that never happened. His brothers teased Francis about his stern tutor, Mr. Craig, a Scottish minister. The year 1750 was painful for Francis and his younger siblings while their older brothers were still in England: Both parents died that year when Francis turned 16. The children inherited a combination of land, money, slaves, and company stock for land speculation in the Ohio River valley. Francis was left “Coton,” an estate in northern Virginia. When the area was named Loudoun County, his brothers began to call him “Loudoun.”

Like his brother Richard Henry, Francis spent many years studying at the Stratford Hall library. Full of energy, Richard Henry drew his brother into many fiery debates. Loudon County named him lieutenant, and Francis left Stratford and moved to “Coton” in 1758. Francis was elected to the General Assembly, although reluctantly, and continued in the House for many years.

In 1766, Richard Henry challenged the British king, writing the Westmoreland Resolutions. Frank signed the seditious act, which later gave a base of the Declaration of Independence. In 1769, at age 35, Francis married his love, Rebecca “Becky” Plater Tayloe of “Mount Airy” in Warsaw, Va., who was 16 years old. They built a home named “Menokin” in Richmond County, Va. Lee was elected to the House of Burgesses, and became good friends with Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson.

To improve the communications within the colonies, Francis and Richard Henry joined Virginia’s “Committee of Correspondence” in 1773. Francis became a member of Virginia’s Convention in 1774. In the next year, Francis was elected to be a delegate for the Second Continental Congress. In 1775, Lee traveled to Philadelphia, and stayed with brother Richard Henry at their sister Alice’s home, and her husband, physician William Shippen, Jr. Francis was described as a well-read man “of gentle reasoning and quiet persuasion.” In mid-June, 1776, Richard Henry was called to Virginia’s General Assembly in developing its’ own constitution. To keep him aware of the action in Philadelphia, Francis wrote a letter July 1:

“This day the resolve for independency was considered & agreed to in Comtee of the whole……Tomorrow it will pass the house with the concurrence of S. Carolina……if our people keep up their spirits, & are determined to be free; whatever advantages the Enemy may gain over us This summer & fall; we shall be able to deprive them of in the winter, & put it out of their power ever to injure us again. Yet I confess I am uneasy, least any considerable losses on our side shou’d occasion such a panic in the Country, as to induce a submission.”

Later in the letter, Francis expressed frustration with the Congress: “…. when all our attention, every effort shou’d be to oppose the Enemy, we are disputing about Government & independence.”

He and 49 delegates signed the Declaration of Independence Aug. 2, 1776. Richard Henry arrived later, and signed Sept. 4: the only brothers who signed the Declaration. Francis participated in the preparation of the country’s first constitution, the Articles of Confederation. Francis was one of only 16 signers of the Declaration who signed both documents.

During that bitter winter of 1777, while the Continental Army froze at Valley Forge, Lee became chair of a special Congressional committee to support the starving army. A story is told that Pennsylvania ignored letters from Congress and denied help from the imploring Army. Lee wrote a critical letter to the governor informing him that Continental commissary would levy Pennsylvania farmers to produce food for the Army. Although it was unconstitutional, that letter worked, and the Army survived to an eventual win the Revolution.

Lee continued in Congress for four years, supporting his brother and their family name. He returned to Virginia, continuing in the House and briefly in the Senate, until 1785. That year, Lee retired at “Menokin” as a country squire. The couple never had children, but gave their inheritance to Richard Henry’s second son, Ludwell, when he showed interest in politics. Both died in January 1797, and were buried at “Mount Airy.”

Biography credit here.

Final Thoughts

Looking at Francis Lightfoot Lee’s life, I see a powerful example of quiet leadership that was just as essential to American independence as the fiery speeches of his contemporaries. While his brother Richard Henry Lee commanded attention with his oratory and bold resolutions, Francis worked behind the scenes, building consensus and ensuring the practical work of revolution got done. His willingness to serve without seeking glory—whether managing correspondence committees, drafting the Articles of Confederation, or ensuring Washington’s starving army received supplies—demonstrates that not all heroes of independence sought the spotlight.

The Lee brothers’ dual signatures on the Declaration of Independence symbolize something profound about the American Revolution: it required both passionate visionaries and steady administrators, both public advocates and private consensus-builders. Francis’s letter to his brother reveals the pragmatic mindset that helped win independence—while others debated grand principles, he focused on maintaining morale and securing victories. His unconstitutional but effective threat to Pennsylvania’s governor to feed Valley Forge troops shows he understood that revolution sometimes required bending rules to achieve greater justice.

Francis Lightfoot Lee’s legacy reminds us that history is shaped not only by those who make grand speeches but also by those who do the quiet, essential work of turning ideals into reality. Though he and Rebecca died childless, they invested their inheritance in the next generation of leadership, showing a commitment to the future of the republic they helped create. In our own time, when public discourse often rewards the loudest voices, Lee’s example encourages us to value the patient coalition-builders, the behind-the-scenes organizers, and the quiet patriots who ensure that noble words become lasting deeds.

Thanks for reading!