T.L.D.R. –

- Age at Signing: 37

- Occupation: Merchant

- Key Perspective/Position: Fired on own home

- Personal Sacrifice: Died poor from spending

- Unique Contribution: Ultimate sacrifice at Yorktown

Introduction

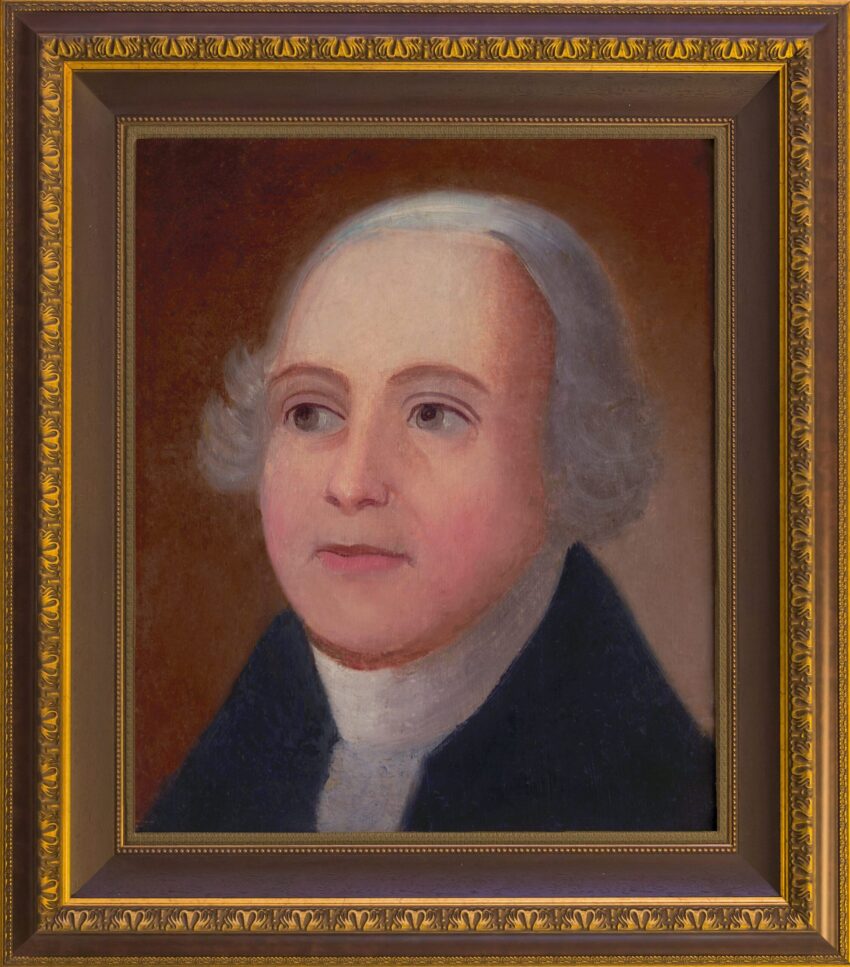

Thomas Nelson Jr. was born December 26, 1738, in Yorktown, Virginia, to one of Virginia’s First Families. He grew up wealthy and attended William and Mary College. In 1762, he married Lucy Grymes, and they had thirteen children.

In 1761, Nelson entered the Virginia House of Burgesses. When patriots protested the Boston Port Bill, Nelson sided against the Royal Governor. He was elected to the Virginia Conventions of 1774 and 1775, where he proposed organizing a militia. Between 1775-1777, he served in the Continental Congress, supporting independence.

In 1781, Nelson was elected Governor to replace Thomas Jefferson. The legislature granted him extensive powers to defend Virginia against British invasion. As Brigadier General, he raised volunteer troops and led militia forces. During the siege of Yorktown alongside Washington and Rochambeau, family tradition says Nelson told Washington to fire on his own home when he heard British officers occupied it. Nelson spent much of his fortune on the cause and died poor on January 4, 1789, at age 50, leaving behind his wife and eleven children.

Contribution to Independence: Nelson literally aimed cannons at his own home for independence, embodying the signers’ pledge of “lives, fortunes, and sacred honor.” His financial sacrifice left him impoverished but helped secure victory at Yorktown.

A Brief Biography

Thomas Nelson, Jr. was born on December 26, 1738, at Yorktown, Virginia, the son of William Nelson and Elizabeth Burwell. He was known as “Junior” because his uncle Thomas Nelson was also of Yorktown. Through his mother’s Burwell family and her Carter ancestors, his family’s history can be traced back to King Henry III in England.

Thomas Nelson’s grandfather, Thomas Nelson, who was known as “Scotch Tom”, was born on February 20, 1677, at Penrith, England (located on the Scottish border) where records indicate he was Baptized in the local Church of England and came to America in 1695, 1698, 1700, and finally 1705. “Scotch Tom” was a merchant and built the first custom house in the colonies. He also built Nelson House about 1740 in the presence of William Nelson and Thomas Nelson, Jr. as an infant. This house is still standing and is a National Historical Landmark maintained by the Colonial National Historical Park of the U.S. National Park Service. This house was occupied by Thomas Nelson, Jr. during the Revolutionary War.

“Scotch Tom” married Margaret Reade in 1710. Her family’s history goes back to Sir Thomas Windebank who was clerk of the signet to Queen Elizabeth I and King James I. Margaret Reade’s ancestor, Richard Reade, was knighted and acquired a property listed in the Domesday Survey, and the Reade family can be traced back to King Edward I and Eleanor of Castile.

Thomas Nelson, Jr., received his primary education from the Reverend Yates of Gloucester County and went to England for additional schooling in 1753. He attended Eton and then entered Christ College at Cambridge where he completed his education 1761. He returned home to the family mercantile business at the age of 23. While still on board his ship on the way back home he was elected to Virginia’s House of Burgesses.

Nelson married Lucy Grymes on July 29, 1762, and they had 13 children, 2 dying in infancy. Through her mother’s family, Mary Randolph, Lucy was the cousin of many of the founding fathers who served with her husband including Peyton Randolph, Benjamin Harrison, Carter Braxton, the Lee brothers and Thomas Jefferson. Her grandfather, Colonel William Randolph, was born in 1651 and came to America from Yorkshire, England in 1674.

Thomas Nelson, Jr. came to manhood just as the colonies began to protest the new direction in the mother country’s colonial policy. In 1774, the House of Burgesses was dissolved by Lord Dunmore because of its resolutions censuring and condemning the closing of the Port of Boston. To protest this action, Nelson began spending some of his personal fortune sending needed supplies to Boston. He arranged a Yorktown tea party and personally threw two half-chests of tea into the York River.

Nelson was elected to represent York County at the first Virginia Convention which met at Williamsburg August 1, 1774. Prominent in the debate over the question of military force, Nelson was appointed colonel in the second Virginia Infantry Regiment in July 1775. He was elected to the House of Delegates in 1776. As a delegate on May 14, 1776, Nelson presented a resolution “that our delegates in Congress be enjoined in the strongest and most positive manner to exert their ability in procuring an immediate clear and full declaration of independency.” This motion was seconded by Patrick Henry and soon adopted. He was then elected to serve in the Second Continental Congress where he replaced Patrick Henry. He took this resolution with him which authorized Richard Henry Lee on June 7, 1776, to move for full independence of the Colonies.

Nelson and Patrick Henry had each been appointed Colonel of a Virginia infantry regiment, but Nelson resigned his commission to take a seat in Congress. Here he voted for independence and signed the Declaration of Independence. Nelson continued his service in Congress but was forced to resign in May 1777 when he experienced a bout of severe asthma. He returned to Virginia and in time recovered sufficiently to lead the Virginia militia in the field.

In the spring of 1781 the Virginia Legislature was on the run while being pursued by the British cavalry into Albemarle County. Nelson was leading the Virginia militia, which had joined with the Marquis de Lafayette, and the Virginia Assembly moved across the Blue Ridge Mountains to reconvene in Staunton. On June 12, 1781, they elected Nelson as Virginia’s third governor. He was notified in his camp on the South Anna River in Hanover County on the 16th and arrived in Staunton on the night of June 18. The following day he was sworn into office to serve both as Governor and military commander of the Commonwealth.

By early September the American and French armies were closing in on Cornwallis who had decided to await evacuation of his army at Yorktown. When the French fleet arrived, Cornwallis’ fate was sealed. During the siege and battle Nelson led the Virginia Militia whom he had personally organized and supplied with his own funds. Legend had it that Nelson ordered his artillery to direct their fire on his own house, which was occupied by Cornwallis, offering five guineas to the first man who hit the house. This story is likely apocryphal since while his home still stands with two cannonballs in its brick walls, while the home of his uncle, Secretary Thomas Nelson for whom he was named, was destroyed. The cannonballs were placed there by the NPS.

Thomas Nelson, Jr.’s personal fortune was ruined by the Revolutionary War. Raising a substantial money to pay for the costs of the militia and other costs of the war, he was never compensated. In November of 1781, illness forced him to resign as Governor. He was replaced by Benjamin Harrison, another Signer. His health, badly effected by his time in the field campaigning, never improved and thus years later while visiting his son’s home “Mont Air” in Hanover County, he died on January 4, 1789. He was only 50 years old. He was buried nearby but was later reinterned in the Grace churchyard at Yorktown. His wife, Lucy, is buried in Hanover County in the Fork Church cemetery.

Nelson’s friend, Dr. Smith, left this account of his death:

“From his unexampled patriotick exertions during the late war he had exhausted a fortune and at the time I mention saw his property arrested, and a prospect of sinking from affluence, almost to absolute poverty. My friend! you can easily conceive the poignant distress of a man in this situation, with an amiable wife and a dozen children around him. He cou’d not bear it. I attended him in his last illness and saw that the exquisite tortures of the mind were the disease that destroyed his body.”

Biography credit here.

Final Thoughts

Thomas Nelson Jr.’s life exemplifies the profound personal cost of founding a nation. While many signers of the Declaration of Independence pledged their “lives, fortunes, and sacred honor,” few paid as dearly as Nelson. From ordering artillery fire on his own home to exhausting his substantial wealth financing Virginia’s militia, Nelson demonstrated that independence demanded more than words—it required absolute commitment. His transformation from wealthy merchant to impoverished patriot stands as a testament to the genuine sacrifices made by America’s founders, reminding us that the birth of our nation came at tremendous personal expense to those who dared to dream of liberty.

The tragedy of Nelson’s final years reveals the harsh reality faced by many Revolutionary patriots. Despite his pivotal role at Yorktown and his service as Virginia’s governor during the state’s darkest hour, Nelson died broken in health and fortune, with creditors seizing his property while his wife and eleven surviving children watched their world crumble. Dr. Smith’s haunting account of Nelson’s death—describing how “exquisite tortures of the mind” destroyed his body—illustrates the crushing weight of seeing one’s family reduced from affluence to poverty. This bitter irony, that a man who helped secure America’s freedom could not secure his own family’s future, underscores the profound inequities often inherent in revolutionary change.

Yet Nelson’s legacy transcends his personal misfortunes. His willingness to sacrifice everything—home, health, and fortune—helped ensure American victory at the crucial Battle of Yorktown, effectively ending the Revolutionary War. The cannonballs embedded in Nelson House serve as enduring symbols of his commitment, while his story challenges us to consider what we would sacrifice for our principles. In an age when patriotism is often reduced to symbols and slogans, Thomas Nelson Jr.’s life reminds us that true love of country is measured not in words but in deeds, not in what we say we would give, but in what we actually surrender when history demands it.

Thanks for reading!