T.L.D.R. –

- Age at Signing: 50

- Occupation: Lawyer

- Key Perspective/Position: Teacher of Jefferson

- Personal Sacrifice: Allegedly poisoned by heir

- Unique Contribution: First law professor

Introduction

George Wythe was born around 1726 in Elizabeth City County, Virginia. He attended William and Mary College and studied law in his uncle’s office. In 1748, he was appointed clerk to House of Burgesses committees, and in 1754, became acting Attorney General—the youngest to hold the position. He married Ann Lewis and later Elizabeth Taliaferro, having one child who died young.

From 1758, Wythe represented William and Mary in the House of Burgesses, mentoring students including Thomas Jefferson. As tensions rose with Britain, he advocated for independence and earned a seat in the Second Continental Congress. Though he returned to Virginia before the Declaration was finalized to help draft the state constitution and design the state seal, his colleagues left space for his signature, which he added in September 1776.

Wythe served as Speaker of the House of Delegates, member of the Virginia Convention, and judge on the High Court of Chancery. Named the first law professor at any American institution at William and Mary, his students included James Monroe and John Marshall. He died in 1806 at age 80, allegedly poisoned by his grandnephew.

Contribution to Independence: Though absent for the vote, Wythe’s earlier advocacy ensured space was left for his signature. His greatest contribution was educating the next generation of American leaders in law and republican principles.

A Brief Biography

George Wythe was born in Elizabeth City County (now Hampton), Virginia on his father’s plantation estate “Chesterville” in 1726, the son of Thomas Wythe III and Margaret Walker Wythe.

His father, Thomas Wythe III, was the grandson of Thomas Wythe senior, who came from Norfolk, England about 1680. Thomas Wythe senior achieved some prominence in Elizabeth City County, serving as justice of the peace and member of the House of Burgesses. He acquired land at the head of Little Poquoson Creek. His grandson, Thomas Wythe III, represented the County in the House of Burgesses, served as a magistrate, and added to the wealth accumulated by the two previous Wythe generations. He was a planter and half-owner of a wharf in Hampton, the principal port in Virginia at the time. He died when George was only three years old.

His mother, Margaret Walker, a Quaker and well educated, home schooled young George. It was she who taught him Greek and Latin. She instilled in her young son a Quaker respect for all mankind, a love of the classics, of logic, and of science that would distinguish him throughout his long life. Margaret Walker was the daughter of merchant George Walker and Ann Keith, and a grand-daughter of George Keith, a “well-known scholar and divine.”

When George Wythe was 14, he entered the Grammar School at William and Mary. After two years there he chose to follow the law, spending two years under the tutelage of his uncle, Stephen Dewey, whose law office was in Charles City Council. At 18 he returned to “Chesterville” where he continued his studies on his own.

In 1746, at the age of 20, he rode to Williamsburg and presented himself for the examination and admittance to the bar. His examiners included Peyton Randolph, a future President of the Continental Congress, and his uncle Stephen Dewey. George passed the bar exam easily and received his license to practice law on June 18, 1746.

Since his older brother Thomas IV was settled at “Chesterville” under the Law of Primogeniture, George moved to Spotsylvania County where he could practice law and live independently. He lived with Zachary Lewis, the King’s attorney, since Lewis needed someone to help with his caseload. George soon took an interest in Lewis’ daughter, Ann, and she and George were married on December 26, 1747, anticipating many happy years of wedded bliss.

But tragedy struck when seven months later, Ann contracted a fever and died. George was distraught, and later wrote that he drowned his sorrow in the inns of Spotsylvania County.

He returned to Williamsburg in 1748 and joined Ann’s uncle, Benjamin Waller, in his law practice there. It was a chance to make a fresh start and begin a social life that included the stimulating company of like-minded academics at nearby William and Mary. That same year he was selected to serve as the clerk of two important standing committees in the House of Burgesses: The Privileges and Elections Committee, and the Propositions and Grievances Committee. His duties as clerk consisted of taking and presenting the minutes of the committee meetings.

Wythe’s talents and connections allowed his law and political life to prosper, and some of his clients included John Blair, a descendant of the founder of William and Mary, Henry Fitzhugh of King George County, and the Custis family whose daughter, Martha Custis, would marry Wythe’s good friend George Washington in 1759.

When Peyton Randolph, the King’s Attorney had a falling out with Royal Governor Dinwiddie, the Governor appointed George Wythe as the King’s Attorney in 1754. This put Wythe in an awkward position as a perceived usurper of one of the most popular men in the colony. This potentially explosive political situation was solved in a few months when the House of Burgesses selected George Wythe to fill the vacancy in the House caused by the death of Armistead Burwell.

In 1755, Thomas Wythe IV died, and his brother George inherited the estate of “Chesterville.” That same year George married Elizabeth Taliaferro, whose family lived at “Powhatan,” about five miles outside Williamsburg. Her father, Richard Taliaferro, a wealthy landowner, and architect, built a handsome brick house for his daughter and new son-in-law in the city. The house stands today, prominently placed between Bruton Parish Church and the Governor’s Palace. It would serve as Wythe’s home for more than thirty years.

George Wythe failed to win re-election to the House of Burgesses twice, but in 1758, he was chosen by the faculty of the College of William and Mary as their representative to the House—a position formerly held by Peyton Randolph.

Governor Francis Fauquier replaced Governor Dinwiddie in 1758, and he and his neighbor George Wythe soon formed a close bond. Wythe, Fauquier and Professor William Small of William and Mary were soon joined by Wythe’s student, the 20-year-old Thomas Jefferson, in 1760, and the four of them often met as a group for dinner at the Palace accompanied by discussions on science, literature, architecture, politics and morals. Jefferson lived with George Wythe for the next five years, and recalled these evenings at the Palace as filled with “more good sense, more rational and philosophical conversations, than in my life beside.”

In 1763, George Wythe and Patrick Henry argued against a controversial tax called the Two Penny Act, saying that the crown had no business meddling in Virginia’s local laws. When news of the hated Stamp Act reached Virginia in 1764, Wythe composed the letter of admonition to Parliament, saying, (The Council and the Burgesses) “conceive it is essential to British liberty, the laws imposing taxes on people, ought not to be made without the consent of representatives chosen by themselves….” When Patrick Henry proposed incendiary resolutions denouncing the Stamp Act, George Wythe and others opposed him on the grounds that they had not yet received a response to their letter from Parliament. But Henry’s resolutions passed, and Governor Fauquier promptly dissolved the General Assembly.

In 1768, Wythe became mayor of Williamsburg, a clear indication of his growing stature and popularity. When John Murray, the Earl of Dunmore, became Governor, he and Wythe often clashed, and Wythe became increasingly estranged from the Royalist cause, and became a firm supporter of the colony’s rights to self-government.

Soon after the outbreak of hostilities at Lexington and Concord Virginians were outraged when it was learned that Lord Dunmore had secretly seized the arms and powder from the magazine in Williamsburg. In June 1775, Lord Dunmore was forced to flee from Williamsburg and he boarded HMS Fowey at Hampton, never to return.

George Wythe traveled to Philadelphia in August to take his place as one of the Virginia delegates in the First Continental Congress. During the continuing debate over independence, he asked his fellow delegates, “In what character shall we treat? As subjects of Great Britain? As rebels? Why should we be so fond of calling ourselves dutiful subjects? We must declare ourselves a free people.” In the spring, he returned to the Virginia Convention to argue in favor of Jefferson’s plan of government for a free and independent Virginia. He returned to Congress and signed the Declaration of Independence in September 1776. One of his final achievements was to move the Continental Congress to appoint Jefferson, Franklin, and Silas Deane as the colonial agents in France—the first ambassadors of what would become the United States of America. Wythe returned to Williamsburg in 1777 and was elected Speaker of the Virginia House of Delegates and assisted Governor Patrick Henry in ensuring that Virginia met its obligations to the Continental Army’s war effort. He remained at his home in Williamsburg during the remainder of the war, dangerously exposed at times to capture. In 1777, George was appointed a justice of the state’s highest court, the Chancery Court, and he served in that capacity for 11 years, until 1788.

After Jefferson became Governor in 1779, he and James Madison, the President of William and Mary, created a new Chair of Law and Police, establishing the first college law curriculum in America. They appointed George Wythe the first Professor of this new department. Wythe held classes in the Wren building and moot courts in the old Capitol building. He also had his students participate in mock legislative sessions to gain experience in parliamentary procedures as well as debate. Some of his more famous law students over the years were Henry Clay, who would become Speaker of the House of Representatives, Littleton Tazewell who would become Governor of Virginia and a U.S. Senator, James Monroe, a future President, and John Marshall, the future Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Marshall’s six weeks with George Wythe were the only legal training he ever received.

On the way to the siege and victory at Yorktown in 1781, General Washington stayed with George and Elizabeth Wythe in their Williamsburg home. Following the war, Wythe spent much of his time working with others to convert the confederation of states into a working constitution. He was a delegate to the Philadelphia Constitutional Convention in 1787, but returned home when he heard that his wife was seriously ill. Elizabeth died on August 18, 1787.

Wythe represented Williamsburg in the Virginia Convention called to ratify the new U.S. Constitution, and in the summer of 1788, he served as Chairman of the Committee of the Whole, guiding discussion and debate. He and Edmund Pendleton provided strong opposition to Patrick Henry and George Mason, who opposed ratification, but the Convention approved the Constitution by a narrow vote, with George Wythe offering the resolution for ratification.

The Virginia legislature created a Court of Appeals in 1788, and George’s frequent chief legal opponent, Edmund Randolph, was named to the Court. Wythe chose to remain as the sole judge in the Court of Chancery. This resulted in no end of grief for Wythe as several of his rulings were overturned by Edmund Randolph. In 1795, Wythe wrote a book taking issue with the Appeals Court rulings.

George Wythe resigned from William and Mary in 1789, and received an honorary degree from the College in 1790. Wythe and one of his students by the name of William Munford moved to Richmond where they took up residence in a house at the southeast corner of 5th and Grace Street. From there Wythe could walk from his house to his Chancery Court chambers in the basement of the capitol. He took advantage of his free time to continue his studies of ancient Hebrew and perform electrical experiments with Munford in a laboratory he created in his home. They lived there for the next 15 years.

In the presidential elections of 1800 and 1804, Wythe served as an Elector in the Electoral College and cast votes for Jefferson.

Freeing his own slaves earlier at “Chesterville,” Wythe wrote this opinion on a slavery dispute in 1806, “…. freedom is the birthright of every human being….”

Around this time, George Wythe Sweeney, the grandson of Wythe’s sister, came to live with him. In 1803, Wythe wrote a will providing generously for Sweeney. When he became aware that Sweeney was stealing from him, he wrote a codicil leaving only half of his estate to Sweeney and half to one of his freed slaves, Michael Brown. Sweeney discovered the will and codicil, and slipping arsenic in food undetected, poisoned Brown and Wythe, and both died. However, Wythe wrote Sweeney out of his will, by a codicil, shortly before he died.

Sweeney also poisoned Lydia Broadnax, Wythe’s housekeeper, and former slave, but she survived. Sweeney stood trial for murder, but was acquitted when Lydia’s testimony was disallowed because she was a Negro.

George Wythe died on June 6, 1806, 80 years of age, and he his buried in the churchyard of St. John’s Episcopal Church in Richmond, the same church where many years before Patrick Henry delivered his famous “Give me liberty, or give me death” speech. A monument plaque was installed at Wythe’s grave by the citizens of Virginia in 1922.

Four days after his death, on June 10, the Richmond Enquirer wrote: “Kings may require mausoleums to consecrate their memory, saints may claim the privilege of canonization; but the venerable George Wythe needs no other monument than the services rendered to his country, and the universal sorrow that the country sheds over his grave.”

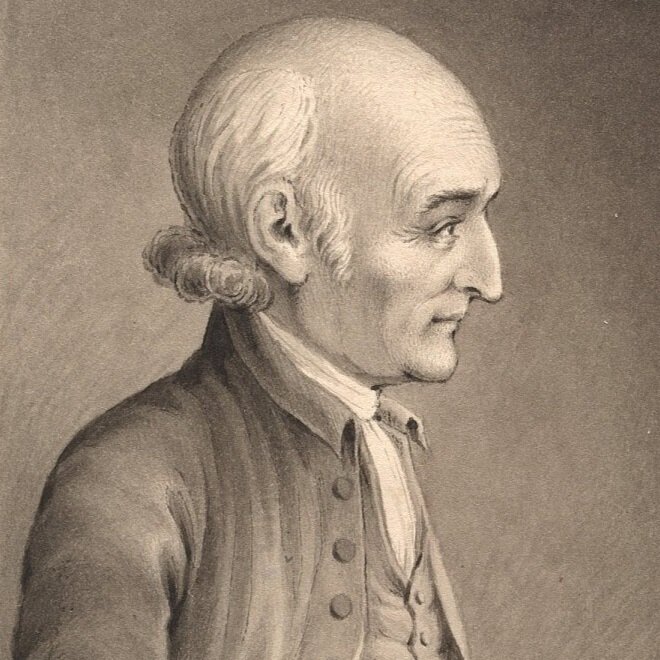

George Wythe was of medium height, well proportioned, unostentatious in appearance and habits, polite and courteous in address. He had blue eyes, a high forehead, and arched brows, along with a solemn and serious demeanor. He ate sparingly, eventually adopting a nearly exclusive vegetarian diet, drank wine moderately and adhered to a rigid schedule of work and studies. He seems to have inherited from his mother a strong constitution as he greatly exceeded the life span of his paternal Wythe ancestors, and could have lived much longer had a murderer not ended his life.

He could seem aloof and dispassionate, particularly when compared with more flamboyant figures such as Patrick Henry. But he could also display a temper, particularly when nettled in the courtroom by his frequently successful opponent, Edmund Pendleton.

One of his students living with him in Richmond, William Mulford, preserved a glimpse of the private life of Wythe, then in his 60s: “Old as he is his habit is, every morning, winter, and summer, to rise before the sun, go to the well in the yard, draw several buckets of water, and fill the reservoir for his shower bath, and then, drawing the cord, let the water fall over him in a glorious shower. Many a time have I heard him catching his breath and almost shouting with the shock. When he entered the breakfast room his face would be in a glow, and all his nerves were fully braced.”

George Wythe was highly regarded by all those who knew him. Thomas Jefferson wrote “No man ever left behind him a character more venerated than George Wythe. His virtue was of the purest tint; his integrity inflexible, and his justice exact; of warm patriotism, and, devoted as he was to liberty, and the natural and equal rights of man, he might truly be called the Cato of his country…. (He was) my faithful and beloved Mentor in youth, and my most affectionate friend through life.”

Fellow signer Benjamin Rush thought George Wythe “a profound lawyer and able politician. I have seldom known a man who possessed more modesty or a more dove-like simplicity and gentleness of manner.”

Wythe brought a strict sense of integrity to the practice of law. He insisted that his clients tell him the truth. If he found that they failed to do so, he would return their fees and refuse to represent them. In a profession not always noted for taking the high moral ground, George Wythe behaved in a way that was beyond reproach. Reverend Lee Massey called George Wythe “the only honest lawyer I ever knew.”

One of his early nineteenth century biographers, Reverend Charles Goodrich, wrote of him in glowing terms: “With all his great qualities, he possessed a soul replete with benevolence, and his private life is full of anecdotes, which prove that it is seldom that a kinder and warmer heart throbbed in the breast of a human being….As a judge, he was remarkable for his rigid impartiality, and sincere attachment to the principles of equity; for his vast and various learning; and for his strict and unwearied attention to business. Superior to popular prejudices, and every corrupting influence, nothing could induce him to swerve from truth and right. In his decisions, he seemed to be a pure intelligence, untouched by human passions, and settling the disputes of men according to the dictates of eternal and immutable justice…. He took a great delight in educating such young persons as showed an inclination for improvement. Harassed as he was with business, and enveloped with papers belonging to intricate suits in chancery, he yet found time to keep a private school for the instruction of a few scholars, always with very little compensation, and often demanding none.” One of his last students in Richmond was a teenager called Henry Clay who went on to become a giant in Congress.

Biography credit here.

Final Thoughts

George Wythe’s life embodied the highest ideals of the American Revolution—not through fiery rhetoric or military glory, but through quiet dedication to law, education, and justice. While his name may not resonate as loudly as those of his students Jefferson, Monroe, and Marshall, his influence permeates the foundations of American jurisprudence and governance. As the first law professor in America, he didn’t merely teach legal precedents; he instilled in his students a profound respect for republican principles and the rule of law. His insistence that “freedom is the birthright of every human being” and his personal act of freeing his slaves demonstrated a moral consistency that many of his contemporaries lacked.

Perhaps Wythe’s greatest contribution to independence was not his signature on the Declaration, but his role in educating and mentoring the architects of the new nation. Through his innovative teaching methods—including mock courts and legislative sessions—he prepared a generation of leaders to govern a republic that existed only in theory. His students would go on to shape the presidency, the Supreme Court, and Congress itself. In this way, Wythe’s influence extended far beyond his own lifetime, creating a multiplier effect that helped transform revolutionary ideals into functioning institutions. His rigorous commitment to integrity in legal practice set a standard that elevated the profession in a young nation desperately in need of ethical exemplars.

The tragic circumstances of Wythe’s death—poisoned by his own grandnephew over an inheritance that included provisions for a freed slave—serve as a dark reminder of the tensions and contradictions of early America. Yet even in death, Wythe remained true to his principles, using his final act to disinherit his murderer. His life stands as testament to the power of education, integrity, and quiet service. While history often celebrates the bold and dramatic, George Wythe reminds us that nations are equally built by those who labor patiently in classrooms and courtrooms, shaping minds and establishing precedents that endure long after the revolutionary fervor has cooled. In training those who would lead America through its formative decades, this “American Aristides” ensured that the promise of independence would be fulfilled not through force, but through law.

Thanks for reading!