In a Futarchy, a traditional democratic model is used to define what a DAO wants to achieve, but betting/prediction markets say how to get there. Said another way, elected representatives formally define and manage an after-the-fact measurement of community welfare, but market speculators decide on the policies that should be put in place to get the community to those chosen ends. The prediction markets of Futarchy solve informational inefficiencies often found in quadratic voting systems, while allowing a DAO to retain egalitarian properties. Further, by separating prediction from control, Futarchy reduces temptation to vote strategically based on herd dynamics rather than sincerely revealing one’s analysis, incentivizing DYOR and solving for the “Tragedy in Commons”.

Shall We Vote On Values, But Bet On Beliefs?

This section introduces Futarchy by quoting from the seminal work of Robin Hanson, Shall We Vote on Values, But Bet on Beliefs?

“Futarchy seems promising if we accept the following three assumptions: Democracies fail largely by not aggregating available information, it is not that hard to tell rich happy nations from poor miserable ones, and betting markets are our best known institutions for aggregating information… Under what I’ve called `futarchy’, we could continue to use democracy to say what we want, but use speculative markets, similar to the stock market, to decide on the best way to get it. Our elected representatives could formally define and manage an after-the-fact measurement of national welfare, an augmented GDP, while market speculators show us which policies will best help us to achieve improvements in it.

The basic rule of government would be this: when speculative markets clearly estimate that a proposed policy would increase national welfare, that policy becomes law. Under a new form of governance, we could formally defer to betting markets on matters of fact, while retaining representative democracy on matters of value. To embed such markets in the core of our form of government, we could “vote on values, but bet on beliefs”.

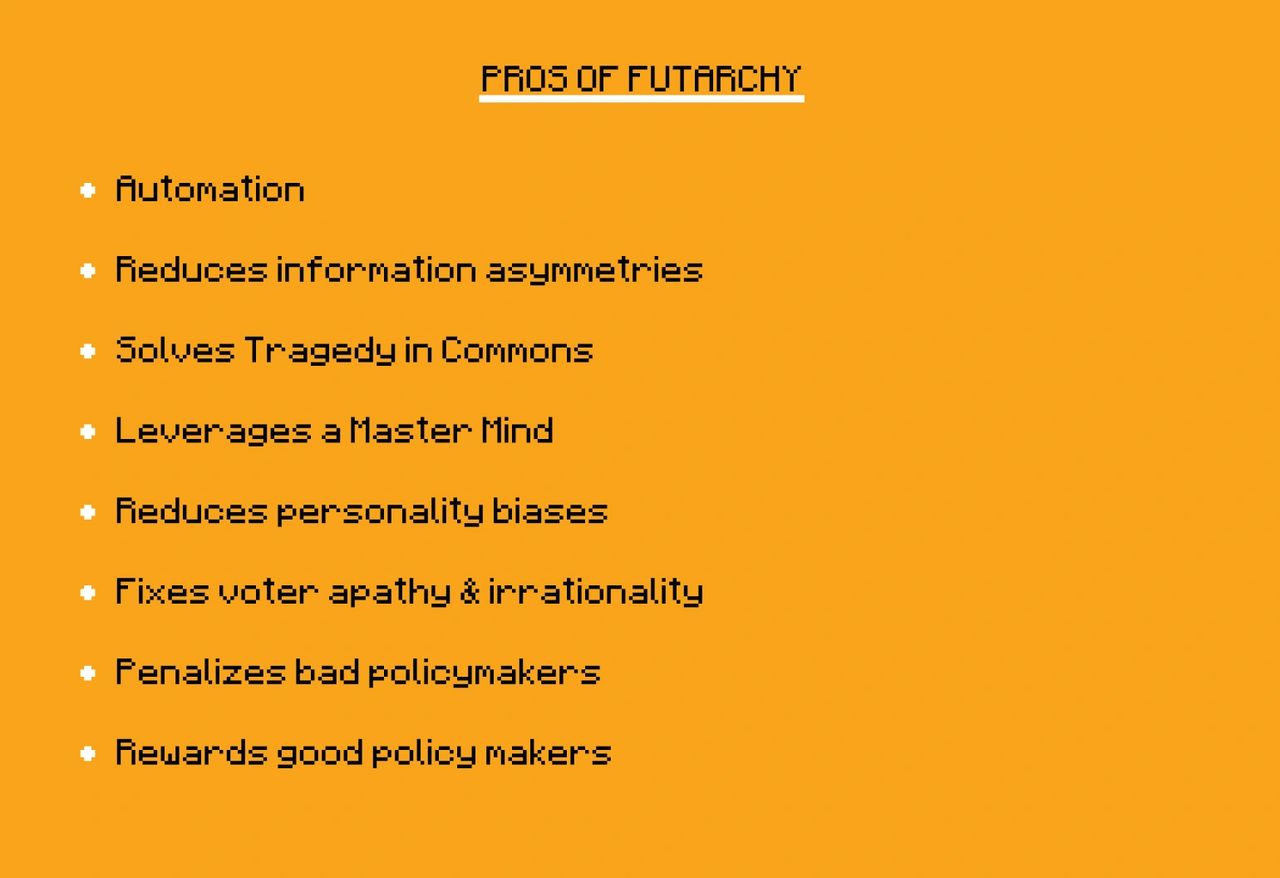

What Are The Pros Of Futarchy?

- Can be fully automated.

- Minimizes information asymmetries.

- Solves for the “Tragedy in Commons” – in both smaller holders and “whales”.

- The system elegantly combines public participation and professional analysis.

- Betting/prediction markets consistently outperform experts, institutions, and polls.

- Leverages a “master mind” collective intelligence and market mechanisms to guide decision-making.

- Reduces personality biases, solving the problem of “herd mentality” – rewards traders who identify predictive sources (individuals, market aggregates) based on past accuracy rather than present popularity.

- Futarchy fixes the “voter apathy” and “rational irrationality” problem in democracy by incentivizing individuals to learn about potentially harmful policies – the probability that their vote will have an effect is insignificant.

- Unlike more rigidly organized and bureaucratic technocracies with a sharp distinction between member and non-member, futarchies allow anyone to participate, set up their own analysis firm, and if their analyses are successful, eventually rise to the top.

- Penalizes bad policymakers and rewards good policy makers – over time the market has an evolutionary pressure to get better; the individuals who are bad at predicting the outcome of policies will lose money, and so their influence on the market will decrease, whereas the individuals who are good at predicting the outcome of policies will see their money and influence on the market increase.

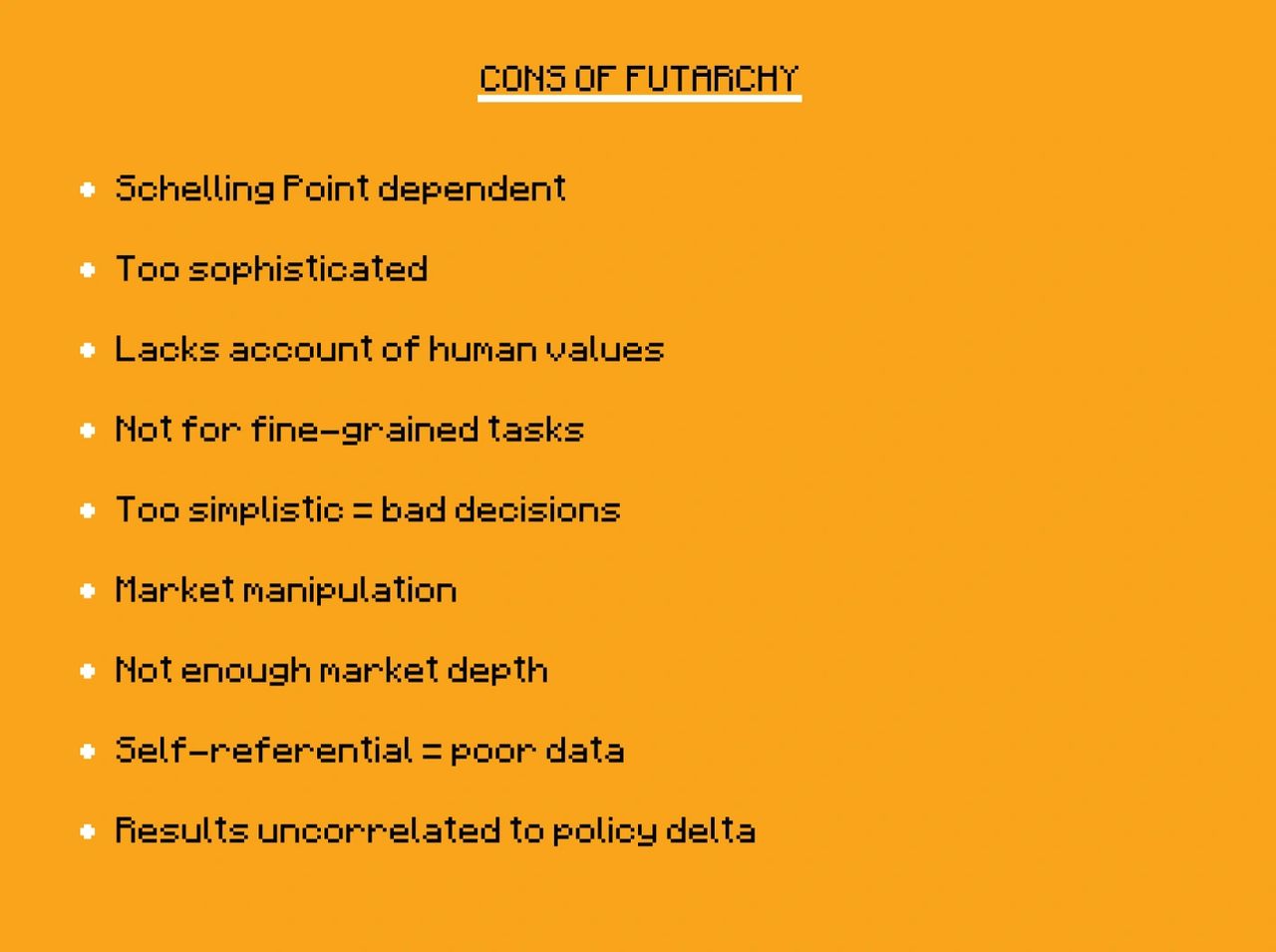

What Are The Cons Of Futarchy?

- Futarchy is Schelling Point dependent.

- Potential for sophisticated voting experience may result in low participation rates.

- Human values are complex, and it is hard to compress them into one numerical metric.

- Futarchy is likely to work well for large-scale decisions, but much less well for finer-grained tasks. Hence, a hybrid system may work better.

- Decision-making, especially public policy decision-making cannot be done properly with such a simplistic process. Inevitably, important considerations are left out of the decision, leading to bad decisions.

- Possible market manipulation by a single powerful entity or coalition – an entity or coalition wishing to see a particular result can continue buying “yes” tokens on the market and short-selling “no” tokens in order to push the token prices in its favor.

- A prediction market is zero-sum; hence, because participation has guaranteed nonzero communication costs, it is irrational to participate. Thus, participation will end up quite low, so there will not be enough market depth to allow experts and analysis firms to sufficiently profit from the process of gathering information.

- Possible market manipulation through volatility – markets in general are known to be volatile, and this happens to a large extent because markets are “self-referential”, as in they consist largely of people buying because they see others buying, and so they are not good aggregators of actual information. This effect can be manipulated.

- The estimated effect of a single policy on a global metric is much smaller than the “noise” of uncertainty in what the value of the metric is going to be regardless of the policy being implemented, especially in the long term. This means that the prediction market’s results may prove to be wildly uncorrelated to the actual delta that the individual policies will end up having.

Why Speculative Markets?

Standard betting markets elicit common estimates that seem to aggregate individual information well, especially when compared to other institutions, and are an exemplary way to collect and summarize information, at least when we eventually learn the outcome. In head-to-head comparisons of the accuracy of the information produced, speculative markets consistently tie or beat everything from surveys to elite committees.

For example, racetrack market odds improve on the predictions of racetrack experts, Florida orange juice commodity futures improve on government weather forecasts, betting markets beat opinion polls at predicting U.S. election results, and betting markets consistently beat Hewlett Packard official forecasts at predicting Hewlett Packard printer sales. To have a say in a speculative market, you put your money where your mouth is. Those who know they are not experts shut up, and those who do not know this lose money, and then shut up.

How Does Futarchy Work?

Futarchy’s speculation markets predict the collective welfare of the DAO, as defined by the DAO’s legislature. This welfare can be defined in any way the legislature chooses. For example, a reasonable initial definition of national welfare, in the case of a Nation State, could augment current measures of national consumption or product (i.e., GDP) with simple measures of health, leisure, happiness, and the environment.

In Futarchy, measurable end-goals, or ‘values’ (“x to be y by z”: where x is a measure – either monetary or otherwise, y is the desired result amount, and z is a time threshold), are voted on in traditional-democratic ways, while “beliefs” or policy that’s enacted in order to reach that end-goal is left to market speculators. If a prediction market favors implementation, the policy is implemented and assessed at the z threshold specified in the value. In other words, enacted policies determined through prediction markets (beliefs) are used to achieve the desired end-goals (values) that are democratically voted on beforehand.

Anyone willing to pay a deposit can put forward a proposal to become policy. Two betting markets then open – one predicting welfare if we adopt the proposal and the other predicting welfare if we don’t. Betting markets can produce conditional estimates several ways, such as via “called-off bets,” i.e., bets that are called off if a condition is not met.

The basic rule is: a day after market prices clearly estimate national welfare to be higher given the proposal than without it, that proposal is adopted.

Final Thoughts

Futarchy represents a fascinating experiment in governance design, attempting to harness the wisdom of markets while preserving democratic values. By separating what we want (values) from how we get there (beliefs), it offers an elegant solution to one of democracy’s persistent challenges: how to make informed decisions when information is scattered across countless individuals with varying expertise.

The core insight is compelling—prediction markets have repeatedly demonstrated their ability to aggregate information more effectively than polls, committees, or individual experts. In a world where policy decisions often fall victim to political theater, cognitive biases, and information asymmetries, futarchy’s market-driven approach promises a more rational path forward.

Perhaps futarchy’s greatest contribution isn’t as a wholesale replacement for existing governance systems, but as a tool in the governance toolkit—particularly well-suited for clearly defined decisions with measurable outcomes.

Thanks for reading!