T.L.D.R. –

- Age at Signing: 26

- Occupation: Lawyer

- Key Perspective/Position: Youngest signer

- Personal Sacrifice: Captured and imprisoned

- Unique Contribution: Persuaded SC delegation

Introduction

Edward Rutledge was born on November 23, 1749, in Charleston, South Carolina, the youngest signer at age 26. Son of Dr. John Rutledge, an Irish immigrant physician, and Sarah Hext, a wealthy South Carolinian, he studied law in England and was admitted to the English Bar in 1772. In 1774, he married the sister of fellow signer Arthur Middleton.

Rutledge’s political career began in 1774 when elected to the First Continental Congress with his brother John. Initially favoring reconciliation, he ultimately supported independence, reportedly persuading South Carolina’s delegation to vote yes on the Declaration. During the war, he served as captain in the Charleston Artillery Battalion. He was captured during the 1780 Siege of Charleston and imprisoned until a prisoner exchange in July 1781.

After the war, Rutledge served in the state legislature from 1782-1798, where he fought against reopening the African slave trade and voted to ratify the Constitution. Elected governor in 1798, he died in office on January 23, 1800, at age 50. He married twice and had three children.

Contribution to Independence: As the youngest signer, Rutledge represented the next generation’s commitment to independence. His capture and imprisonment demonstrated the real dangers signers faced.

A Brief Biography

Edward Rutledge was born in Charleston, South Carolina on November 23, 1749. He was the youngest son of Dr. John Rutledge, who emigrated from Ireland to South Carolina about the year 1735. A diligent Rutledge family historian on the internet has ascertained that Edward was the grandson of Thomas Rutledge who lived in Callan, County Kilkenny, Ireland, about 65 miles southwest of Dublin.

Edward’s mother was Sarah Hert, a “lady of respectable family, and large fortune.” Sarah’s grandfather, Hugh Hext, came to South Carolina from Dorsetshire, England about 1686. Sarah’s father, also named Hugh, left to his “dearly beloved and only daughter” substantial lands inherited from the Fenwick family, two homes in Charleston, a 550-acre plantation at Stono, and 640 acres on St. Helen’s in Granville County.

Not a lot is known about the early years of Edward Rutledge, but we do know that he was placed under the tutelage of David Smith who instructed him in the learned languages. He was not a brilliant student, but his skill as an orator later in his life perhaps is due in part to this early experience. After this education Edward read law with his elder brother John, who was already a distinguished member of the Charleston bar.

When he was twenty years of age, Edward Rutledge sailed for England and became a student of law at the Temple. He had the experience there of listening to some of the most distinguished orators of the day, in court and in parliament, a precursor to his later ability. The Temple in London was an ancient institution for teaching law founded by the Knights Templar in the reign of Henry II in 1185. The Inner Temple, where Edward studied, became an Inn of Law in the reign of Edward III about 1340. The Temple was a prominent source for teaching law to many famous South Carolinians including Edward’s uncle Andrew Rutledge, Edward’s brothers John and Hugh, Arthur Middleton, Thomas Lynch, Jr., Thomas Heyward, Jr., and several members of the Pinckney family.

Rutledge returned to Charleston in 1773 to practice law. He quickly gained recognition as a patriot when he successfully defended a printer, Thomas Powell, who had been imprisoned by the Crown for printing an article critical of the Loyalist upper house of the colonial legislature. Despite his youth (he was only 24 at the time), he earned a reputation for his quickness of apprehension, fluency of speech and graceful delivery.

Soon after he established his law practice, Edward married Henrietta Middleton, the sister of Arthur Middleton who would also sign the Declaration of Independence. The couple had a son and a daughter, and a third child who died as an infant. After the death of his first wife in 1792, Rutledge married Mary Shubrick Eveleigh, a young widow. This marriage continued the inter-relationship among the signers of the Declaration, since two of Mary Shubrick’s sisters had married signers of the Declaration—one married Thomas Heyward, Jr. and one married Thomas Lynch, Jr.

Henrietta’s great-grandfather was Edward Middleton, who was born in 1620 and came to the Barbados in 1635 on the Dorsetand settled in South Carolina in 1678. He was Lord Proprietor’s deputy, assistant justice, and a member of the Grand Council from 1678 to 1684. Henrietta’s grandfather, the Honorable Ralph Izard, was born in England and came to South Carolina in 1682.

Rutledge enjoyed a happy home life and public success in the succeeding years. He was first elected to the Continental Congress and the South Carolina House of Representatives. In both bodies, his increasing self-confidence and maturation of judgment brought him the esteem of the delegates.

In 1775, Rutledge seemed favorably disposed to the idea of independence. In his autobiography John Adams recalled, “In some of the earlier deliberations in Congress in May 1775, after I had reasoned at some length on my own Plan, Mr. John Rutledge (i.e., Edward’s brother) in more than one public speech, approved of my sentiments and the other Delegates from that State Mr. Lynch, Mr. Gadsden and Mr. Edward Rutledge appeared to me to be of the same mind.”

But when the debate began over Richard Henry Lee’s resolution for independence in June 1776, Rutledge was vigorously opposed. In a letter to John Jay, Rutledge wrote, “The Congress sat till 7 o’clock this evening in consequence of a motion of R. H. Lee’s resolving ourselves free & independent states. The sensible part of the house Opposed the motion…They saw no wisdom in a Declaration of Independence, nor any other purpose to be answered by it…No reason could be assigned for pressing into this measure, but the reason of every Madman, a shew of our Spirit…The whole Argument was sustained on one side by R. Livingston, Wilson, Dickenson & myself, & by the Powers of all N. England, Virginia & Georgia on the other.”

When a trial vote on independence was taken on July 1, the South Carolina delegates voted “no”. Rutledge then asked for a one-day postponement of the vote and met with his South Carolina colleagues that night. He persuaded them to support Lee’s motion, and next day South Carolina reversed its course, making the official vote for independence unanimous, 12 to 0, with New York abstaining. Rutledge signed the Declaration in August, at age 26 the youngest signer of the Declaration of Independence.

In the stage play and then movie “1776”, the character of Edward Rutledge is portrayed as the leader in the opposition to the slavery reference in Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration. There seems to be no corroboration of this in the written record, although Rutledge proved to be a passionate defender of South Carolina’s state rights throughout his tenure in the Continental Congress. Later in his career, during his tenure in the South Carolina House of Representatives, he opposed the opening of the African slave trade. This provides a remarkable insight into his sense of belief in the dignity of all human beings, as his fortune had been built on the backs of slaves working on his rice plantations.

In June 1776, before the vote for independence, Rutledge was chosen to represent South Carolina on a committee to draft the country’s first constitution, the Articles of Confederation. Again, Rutledge shared his reservations about the Articles with John Jay. “I greatly curtailed it never can pass…If the Plan now proposed should be adopted nothing less than Ruin to some Colonies will be the Consequence of it. The Idea of destroying all Provincial Distinctions… …is…to say that these Colonies must be subject to the Government of the Eastern Provinces…I am resolved to vest the Congress with no more Power than what is necessary.” The Confederation was heatedly debated by the Congress for many months about representation, state boundaries, taxation, and the powers of the new central government. The Articles were not completed and signed until November 15, 1777, and were not ratified by the last state until 1781.

In September 1776, Edward Rutledge, John Adams and Benjamin Franklin were selected by Congress to attend a meeting at the Billopp House on Staten Island, requested by Lord Admiral Richard Howe. The meeting was pleasant but nothing was accomplished.

After the meeting Rutledge wrote to his close friend General Washington, whom he greatly admired, to tell him about the meeting. “I must beg Leave to inform you that our Conference with Lord Howe has been attended with no immediate Advantages. He declared that he had no Powers to consider us an Independent States, and we easily discovered that were we still Dependent we should have nothing to expect from those with which he is vested. He talked altogether in generals, that he came out here to consult, advise & confer with Gentlemen of the greatest Influence in the Colonies about their Complaints…This kind of Conversation lasted for several Hours & as I have already said without any effect…. Our reliance continues therefore to be (under God) on your Wisdom & Fortitude & that of your Forces. That you may be as successful as I know you are worthy is my most sincere wish…God bless you my dear Sir. Your most affectionate Friend, E. Rutledge.”

Rutledge continued to serve in the Congress, but illness prevented Rutledge from taking his seat in Congress in 1779, and he returned home. He was appointed a lieutenant colonel in the Charleston Battalion of Artillery, and served under General William Moultrie in the victory over the British forces under Major Gardiner, driving them from Port Royal Island. A year later, he was taken prisoner during the British siege of Charleston on May 12, 1780, along with Thomas Heyward and Arthur Middleton. Rutledge was held in a prison off the coast of St. Augustine for eleven months and was exchanged in July 1781. He began a long 800-mile journey to return home.

Edward Rutledge held a variety of distinguished public offices until 1798. He served in the South Carolina legislature from 1782 to 1798, and voted in favor of ratification of the U.S. Constitution in the South Carolina Constitutional Convention in 1790-1791. During his time in the legislature drew up the act which abolished primogeniture, worked to give equitable distribution of the real estate of intestates, as well as voting against opening the African slave trade, as mentioned earlier.

During this period the wealth of the Rutledge family increased substantially–his law practice flourished, and in partnership with his brother-in-law, Charles C. Pinckney, he invested in plantations.

Rutledge declined President George Washington’s offer of a seat on the U.S. Supreme Court in 1794, but ran for office and was elected Governor of South Carolina in December 1798.

The accomplishments of Edward’s older brother, John Rutledge, rivaled those of Edward’s. John was an early delegate to the Continental Congress, President of South Carolina from 1776 to 1778, Governor of South Carolina in 1779, a member of the Constitutional Convention in 1787, a signer of the U.S. Constitution, a Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1789 to 1791, and was appointed Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court by President George Washington in 1795, despite his opposition to the Jay treaty with Great Britain.

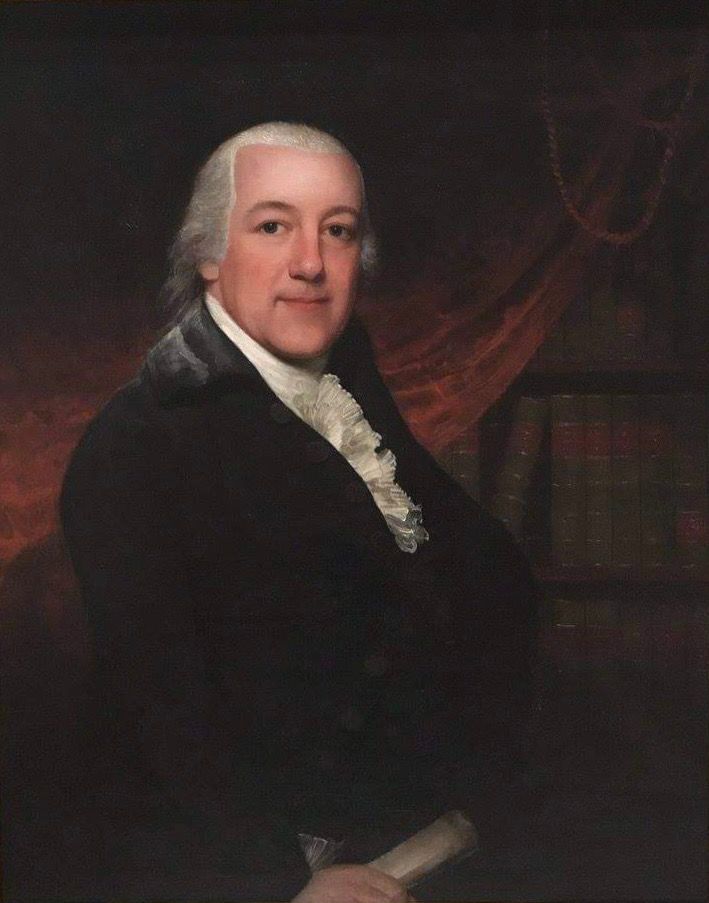

In his person Rutledge was above the middle size and of a florid but fair complexion. His countenance expressed great animation, and he was universally admired for his intelligent and benevolent aspect. He was undoubtedly an orator of great power and eloquence, and a “genial and charming gentleman.”

Despite his many honors, the temperament and character of Edward Rutledge were sometimes controversial. In 1774, John Adams considered him “a peacock who wasted time debating upon points of little consequence.” He went on to describe him as “a perfect Bob-O-Lincoln, a swallow, a sparrow…jejune, inane and puerile.” Benjamin Rush, however, thought Rutledge to be a sensible young lawyer and useful in Congress, but also remarked on his “great volubility in speaking.”

Patrick Henry, by comparison, viewed Rutledge as the greatest orator among a group that included John and Samuel Adams, John Jay, and Thomas Jefferson. It was said that the eloquence of Patrick Henry was as a mountain torrent, while that of Edward Rutledge was like a smooth stream gliding along the plain—that the former hurried you forward with a resistless impetuosity, while the latter conducted you with fascinations, that made every progressive step appear enchanting.

Edward Rutledge died in Charleston on January 23, 1800 while he was still Governor and was buried in St. Philip’s Churchyard Cemetery in Charleston, South Carolina. His loss was mourned by the people of Charleston and South Carolina, and impressive military and funeral honors were paid to him on his death. In 1969, an historical marker was installed at the entrance to St. Philip’s Churchyard by the South Carolina Daughters of the Revolution, honoring both Edward Rutledge and Charles Pinckney. In 1974, the National Park Service designated St. Philip’s Church a national historical landmark.

Biography credit here.

Final Thoughts

Edward Rutledge’s life embodied the complexities and contradictions of the founding generation. As the youngest signer of the Declaration of Independence at just 26 years old, he represented both youthful idealism and pragmatic caution. His initial opposition to independence, followed by his pivotal role in persuading South Carolina to support the measure, demonstrates the careful deliberation that preceded this momentous decision. His capture and imprisonment during the war proved that his signature was more than a symbolic gesture—it was a commitment that carried real personal risk and sacrifice.

Rutledge’s career reveals the nuanced nature of early American leadership. While he built his fortune on slave labor, he later opposed reopening the African slave trade in the South Carolina legislature, suggesting an evolving conscience or at least a recognition of the institution’s troubling implications. His fierce defense of state rights while simultaneously working to build a unified nation reflects the delicate balance the founders sought between federal authority and local autonomy. His legal career, from defending a printer’s freedom of speech to drafting legislation abolishing primogeniture, shows how the revolutionary generation worked to dismantle old hierarchies while grappling with which new ones to maintain.

The legacy of Edward Rutledge reminds us that the American founding was not the work of demigods but of complex individuals navigating unprecedented challenges. His eloquence, described as a “smooth stream gliding along the plain,” helped shape crucial debates in both Continental Congress and South Carolina politics. His life—cut short at age 50 while serving as governor—encompassed the full arc of the revolutionary era: from colonial resistance through independence, war, and the establishment of constitutional government. In remembering Rutledge, we see both the achievements and limitations of the founding generation, and the ongoing work of forming “a more perfect union” that each generation must continue.

Thanks for reading!