T.L.D.R. –

- Age at Signing: 38

- Occupation: Artist/Lawyer

- Key Perspective/Position: Renaissance man

- Personal Sacrifice: Created patriotic art/music

- Unique Contribution: Designed early flag version

Introduction

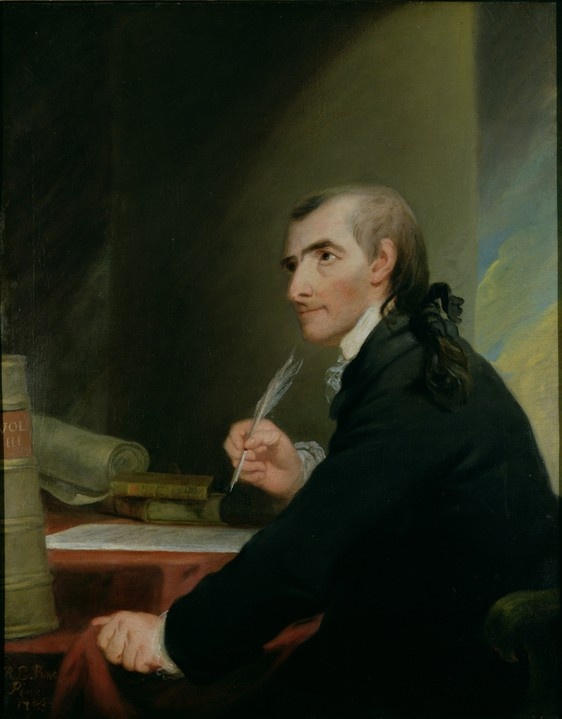

Francis Hopkinson was born on October 2, 1737, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the eldest of eight children of a prominent political leader. He graduated from the first class of the College of Philadelphia (now University of Pennsylvania), studied law, and opened a practice in New Jersey. In 1768, he married Ann Borden, and they had five children.

A true Renaissance man, Hopkinson was a musician, poet, artist, satirist, inventor, jurist, and writer. His 1759 composition “My Days Have Been So Wondrous Free” is considered the first secular song by an American. He authored “Temple of Minerva” in 1781, recognized as America’s first opera.

In 1776, Hopkinson represented New Jersey in the Continental Congress and later served as chairman of the Continental Navy Board, treasurer of loans, and judge of the admiralty court of Pennsylvania. He expressed patriotism through satirical writings supporting independence and is credited by some historians with designing an early version of the American flag. He died in Philadelphia on May 9, 1791, at age 53.

Contribution to Independence: Hopkinson used his artistic talents to support independence through music, satire, and political writings. His cultural contributions helped create a distinctly American identity during the Revolutionary period.

A Brief Biography

Francis Hopkinson was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on 21 September 1737 (o.s.), the eldest of the eight children born to Thomas Hopkinson and Mary Baldwin Johnson. His father died when the lad was only 14 years of age, but his mother wanted to make sure he had the advantages of a good education, and saw to it that at age 16 he matriculated at the brand-new College of Philadelphia [later to become the University of Pennsylvania] as a member of its first class, graduating with a B.A. Degree in 1757, and three years later, in 1760, was granted an M.A. Degree. Francis read law with Benjamin Chew, the Attorney-General for the Colony of Pennsylvania, and was admitted to the Bar in 1761.

Armed with an excellent education and a very wide range of interests, Francis Hopkinson, began working as a Secretary to the Provincial Council of Pennsylvania Indian Commission during which he helped to make treaties with the Delawares and several of the Iroquois tribes. His efforts as an attorney were not very productive, so he sought out and received a position as Customs Collector for Salem, New Jersey. He also tried his hand at a business venture, but that too did not yield the return he hoped for.

Seeking a more remunerative position, Hopkinson took ship for England in May 1766, with the hope of securing a situation as Customs Commissioner for North America. He tried using the patronage of the Prime Minister, Lord North, and his half-brother, the Bishop of Worcester in this endeavor, but was unsuccessful; although these contacts gave him a much wider and broader view of world trading practices, politics, and the workings of Parliament. During his stay in London, he did meet and took some painting lessons from Benjamin West. Having exhausted his contacts in England for a position, he returned to America in August 1767.

Hopkinson was a multi-talented person: writing, painting, music, design, politics, law. As a young man he played the harpsichord and the organ; composed several pieces, and copied arias, songs, and instrumental pieces by several European composers. After his return to America, Hopkinson married Ann Borden, daughter of Colonel Joseph Borden and Elizabeth Rogers in Bordentown, New Jersey on 1 September 1768. They had a total of nine (9) children, four of whom died young, and five of whom married and had issue [See Volume 3, 2nd Edition, Part 1, of The Genealogical Register of the Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence, Picton Press, 2009, p. 198].

He obtained a public appointment as a Customs Collector for New Castle, Delaware on 1 May 1772. Moving to Bordentown in 1774, Hopkinson became an Assemblyman for the New Jersey Royal Provincial Council. He was admitted to the New Jersey Bar on 8 May 1775, resigned his crown appointed positions in 1776, and was elected to be a Delegate to represent New Jersey in the Second Continental Congress on 22 Jun 1776. He was present on 2 July 1776, and voted for the resolution of Richard Henry Lee, that these Colonies are and of right ought to be free and independent States…, participated in the debates regarding the language on 3 & 4 July 1776, and signed the Declaration on 2 August 1776. He left the Congress on 30 November 1776 to give more time to his law practice and to serve on the Navy Board in Philadelphia.

Hopkinson was a treasurer of the Continental Loan Office in 1778, appointed Judge of the Admiralty Court of Pennsylvania in 1779 and reappointed in 1780 & 1787. Strongly in favor of a united nation, he argued positively for the Articles of Confederation, urging those states with “western” claims of land to give them up to the Congress. Serving in the New Jersey Assembly, he helped to see that the Constitution of 1787 was ratified by Delaware [7 December 1787], Pennsylvania [12 December 1787], and New Jersey [18 December 1787], as he spoke and wrote to people in those areas that he knew. After George Washington was inaugurated in New York as the 1st President of the United States, Francis Hopkinson was appointed by him to be Judge of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, receiving his Commission on 26 September 1789.

The oeuvre of Hopkinson’s music, writings, and artistic contributions is quite large. He was a fine amateur musician and composer, writing several songs and ballads throughout the decade of the 1760’s. Many of his writings are found in Miscellaneous Essays and Occasional Writings, published in Philadelphia. He prepared a design for the flag of the United States in 1777, although his design was not used, it did provide some guidance to the makers of the flags that were used. Hopkinson also prepared seals for several of the early Federal entities in 1780: The Board of Admiralty, The Treasury Board for use with the Continental Currency, and served on the committee to prepare the Great Seal of the United States of America.

He continued to participate in community affairs, being the treasurer of the American Philosophical Society from 5 January 1781 to 12 January 1791. Serving as Judge of the United States District Court for Eastern Pennsylvania, from the time of his Commission in 1789, Francis Hopkinson died in Philadelphia on 9 May 1791. He is interred in the Churchyard of Christ Church, Philadelphia.

Biography credit here.

Final Thoughts

Francis Hopkinson embodied the spirit of the American Enlightenment, demonstrating that the founding of the nation required not just political courage, but cultural vision. While his fellow signers wielded pens to draft laws and muskets to wage war, Hopkinson wielded brushes, quills, and musical notes to forge an American identity. His satirical writings mocked British authority with wit rather than vitriol, his compositions gave voice to American aspirations, and his designs helped visualize what independence might look like. In an age when most men specialized in a single profession, Hopkinson’s Renaissance versatility made him uniquely suited to help birth a nation that needed everything from flag designs to naval administration.

Despite his extraordinary talents and contributions, Hopkinson remains one of the lesser-known signers of the Declaration of Independence. Perhaps this relative obscurity stems from the quiet nature of cultural influence compared to battlefield glory or fiery oratory. Yet his impact was profound: through art, music, and satire, he helped Americans imagine themselves as a distinct people worthy of self-governance. His work on early American symbols, including his flag design proposal and contributions to federal seals, helped create the visual language of the new republic. While he may not have commanded armies or delivered famous speeches, Hopkinson’s creative output provided the cultural foundation upon which political independence could flourish.

Hopkinson’s life reminds us that revolutions require more than political theorists and military strategists—they need artists, musicians, and visionaries who can articulate what a new society might become. His willingness to resign comfortable crown appointments in 1776 demonstrated that even those who worked through art rather than arms understood the gravity of their choice. From his early satirical pieces supporting independence to his later work establishing federal institutions, Hopkinson dedicated his diverse talents to the American experiment. In signing the Declaration at age 38, this Philadelphia polymath pledged not just his life, fortune, and sacred honor, but his creative genius to the cause of American independence.

Thanks for reading!