T.L.D.R. –

- Age at Signing: 50

- Occupation: Landowner

- Key Perspective/Position: Firm when NY wavered

- Personal Sacrifice: Three sons served under Washington

- Unique Contribution: Stayed course despite NY hesitation

Introduction

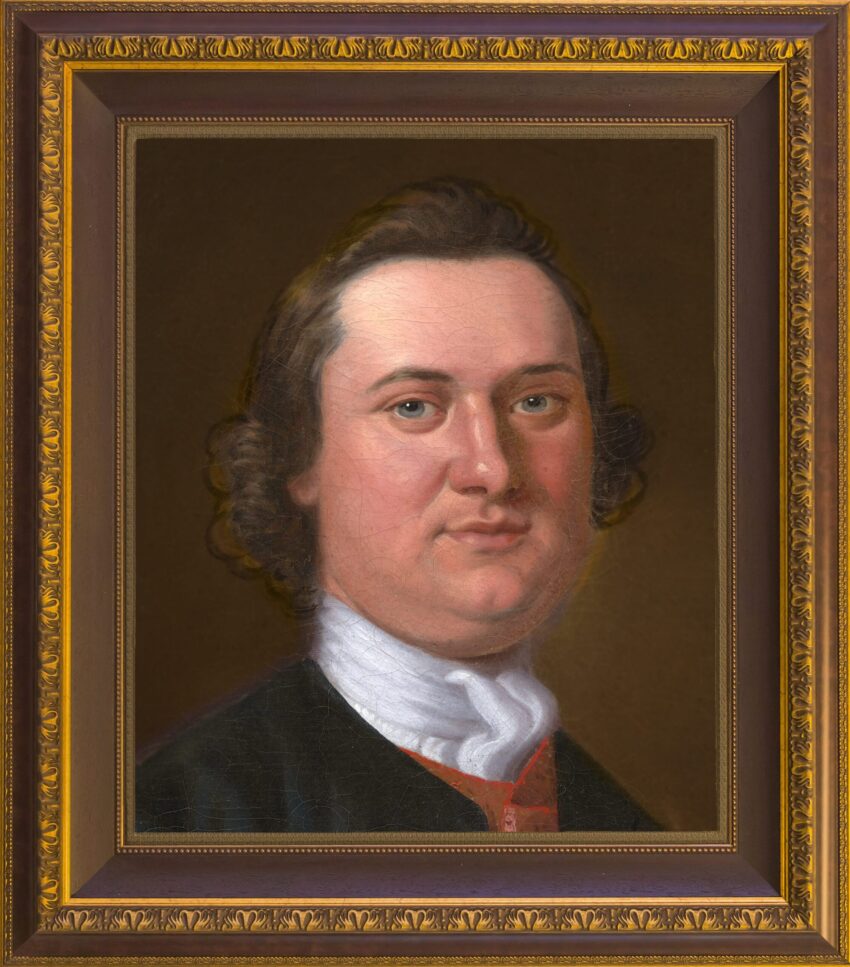

Lewis Morris was born on April 8, 1726, in Westchester County, New York. He attended Yale College and married Mary Walton, with whom he had ten children. As the eldest son, he inherited his father’s estate at Morrisania, New York, along with properties in New Jersey.

Growing frustrated with British trade policies, Morris became a fierce proponent of independence. Elected to the Second Continental Congress in 1775, he was sent to persuade Native Americans not to join the British cause. While New York’s provincial congress was reluctant to endorse independence, Morris held firm in his support.

During the war, Morris served as Brigadier General in the Westchester County Militia, and all three of his sons served under Washington. After independence, he served as Judge of Westchester County, New York State Senator, member of the first Board of Regents of the University of New York, and delegate to the 1788 state convention that ratified the Constitution. He died at Morrisania on January 22, 1798, at age 71.

Contribution to Independence: Morris remained steadfast for independence even when New York hesitated, demonstrating the personal convictions that drove individual delegates beyond their colonies’ official positions.

A Brief Biography

Lewis Morris was the eldest son, second child of Lewis Morris and Tryntje Staats. He was born in the Manor of Morrisania, in Westchester County, NY (now in the Bronx), on 8 April 1726. He is descended from the emigrant, Richard Morris, an officer in Cromwell’s army, who left England for New York at the time of the Restoration (1660). Lewis Morris was tutored at home, and then entered to Yale at age sixteen, from which he graduated in 1746.

He married Mary Walton, daughter of Jacob and Maria (Beekman) Walton on 24 September 1749. By her he had six sons and four daughters. She was born in New York City on 14 May 1727, and died at Morrisania on 11 March 1794. When his father died in 1762, the son became the Third Lord of the Manor of Morrisania.

The closing of the “Old French War,” now more generally known as the Great War for Empire, the French and Indian War, or the Seven Years War between England and France, brought the French-Indian incursions upon the colonial frontiers to an end. New England, New York, and Pennsylvania had been particularly hard hit by these raids, and the people were glad to see them ended, and proud that they, as Englishmen, had contributed to the victory.

But, hardly had the ink dried upon the Treaty of Paris in 1763, before the British Parliament began enacting laws and procedures that were confining and restrictive to the colonists. Lewis Morris spent most of his time and effort managing his extensive properties in New York and New Jersey. He was appointed a Judge of the Court of Admiralty in 1760, from which position he resigned in 1774. He was elected to the Colonial Assembly of New York in 1769, and a delegate to the Provincial Assembly in April 1775.

During these years, Morris became less and less enchanted with the way the British acted and tried to dominate the internal as well as external trade among the colonies and with other countries. Though residing in a pro-Loyalist area, with neighbors holding strong views of affection, warmth and loyalty to the King, Morris became increasingly critical of British policy. As new laws were heaped upon older laws, and became more restrictive, he began to lean in the direction of the liberty seeking people both in the colony and the city of New York and the surrounding areas. It became increasingly difficult to ship goods to any other place. One could not trade unless the goods were shipped in English bottoms, and passed through English ports.

Elected as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress from New York, Morris, took his seat in Philadelphia on 15 May 1775. He was quickly placed on a committee, with George Washington as chair, to address the problems of supplying military stores, arms, and ammunition to the army. At the close of the session of Congress, Lewis Morris was sent to the western country to assist with inducing the Indians to either make common cause with the colonists, or at least remain neutral. He remained at Pittsburgh throughout the winter, returning to his seat in the Continental Congress by early March 1776.

During his winter stay on the western frontier, the issue of “independency” had circulated among the colonies and the people. Thomas Paine’s powerful language had made quite an effect upon very many folks. Those who, heretofore, were either reluctant or opposed to the idea, began to turn things over in their mind. If King and Parliament could not see their way to embracing the colonists, then, just maybe, it might be time to separate! Lewis Morris did not side-step this issue. Perhaps a year earlier, he might have been interested in some proposal for accommodation. Now, however, he saw that such a prospect was out of reach. Too much blood had been spilled, too many peaceful overtures turned aside with disdain by the King (declaring us “out of his protection”). The stiff attitude toward Americans that prevailed among the English, strongly suggested that they were unwilling to even listen to reason, let alone come to any “accommodation.”

Independence was the only way! The problem with New York was that the Provincial Assembly felt that they had to walk somewhat lightly on this subject, because there was still a strong influence toward British thinking among some of the powerful merchants and political appointees in the city. So, the Assembly held back on the matter, until after the efforts of all the other colonies had brought forth a consensus upon independence on 2 July 1776, and upon a Declaration of the same on 4 July 1776. Finally on 9 July 1776, the New York Assembly agreed to support Independence, and that vote was promptly carried to Philadelphia, where the New York delegation could now heartily approve, making the Declaration of Independence a unanimous action on 11 July 1776!

The British gathered a huge armada and thousands of troops, and descended upon New York, defeating the American Army in the Battle of Long Island on 27 August 1776. The victors soon spread desolation over Long Island, Westchester County, and many nearby areas of the Colony of New York. The fields, woodlands, crops, and property at Morrisania were nearly destroyed, the manor house injured, fences burned, stock consumed or driven away. Like so many men of property who clung to the idea of freedom and liberty, the cost was high, both in terms of monies lost, stolen or no longer usable; as well as well-being, and physical harm.

Lewis Morris left the Continental Congress in 1777 to serve his County and State; as Judge of Westchester County in 1777 and member of the Committee on Detection of Conspiracies; as a Senator in New York from 1777 to 1781, and 1784 to 1788. Morris also served in the Westchester County Militia, rising to the rank of Major General. He was a member of New York’s first Board of Regents of the University of New York, serving from 1784 to his death in 1798. Morris was also a delegate to the State Convention that ratified the Federal Constitution in 1788. Thus, we see that Lewis Morris, gave of himself, his time, and talents to the public in a variety of positions, using his influence, his skills, and his knowledge to the benefit of the people.

Interspersed between his political duties and his public duties, following the end of the Revolutionary War in 1783, Lewis Morris, turned as much of his attention as possible to the thing he truly enjoyed the most—the management of his property at Morrisania. As Lord of the Manor, he took that position most seriously. He worked hard at restoring the farmlands and the crops that had been destroyed by the British occupancy. He spent much time learning about agricultural advances, crop rotation, soil improvement, and seed mutations.

He introduced new and hardy stock, tried several cross-breeds of cattle and hogs. Always supportive of education, Morris introduced and pushed for more and better public education throughout the entire State of New York. His work with the Regents Office gave him the opportunity to see how useful higher standards of an educated populace could become. He also agreed with Philip Schuyler that an improved travel system of roads and canals would enhance trade and the movement of goods and people.

In his capacity as State Senator, Lewis Morris, was very active in introducing bills and legislation that would ease the way for the many improvements he sought. He continued to find means of implementing, securing funding for, and following up upon all these many projects. Not all the ideas Morris would like to have seen come to fruition, did so in his lifetime, but many of these ideas had a seed planted that bore fruit within the next generation.

Approaching his seventy-second year, surrounded by the improvements he brought to his beloved Morrisania, and his children and grandchildren, Lewis Morris died on 22 January 1798 at Morrisania, and is interned in a vault beneath St. Anne’s Church there.

Biography credit here.

Final Thoughts

Looking at Lewis Morris’s life through the lens of the Declaration of Independence, we see a man whose commitment to liberty grew from personal conviction rather than political convenience. While many of his New York neighbors remained loyal to the Crown, and even his own colony’s assembly hesitated to embrace independence, Morris stood firm in his belief that separation from Britain was necessary. His transformation from colonial judge to revolutionary reflects the journey many Americans took during this period – from frustrated subjects seeking accommodation to determined patriots willing to risk everything for freedom. His steadfastness when New York wavered demonstrates how individual courage often preceded collective action in the movement toward independence.

The personal cost Morris paid for his principles was substantial and deeply felt. His estate at Morrisania, built through generations of family effort, was ravaged by British forces who targeted the property of known patriots. Yet Morris never wavered, even as he watched his fields burn and his livestock driven away. Perhaps most poignantly, all three of his sons served under Washington, putting the entire next generation of the Morris family at risk for the cause. This wasn’t abstract political philosophy – it was a father watching his children march off to war, knowing they might never return. The sacrifice of property could be rebuilt, but the potential loss of his sons represented the ultimate price a parent could pay for freedom.

Morris’s post-war career reveals something essential about the founding generation – they understood that declaring independence was only the beginning. While he could have retreated to rebuild his damaged estate, Morris instead threw himself into building the institutions that would make the new nation sustainable. His work as a state senator, constitutional ratification delegate, and education advocate shows a man who understood that true independence required strong civic foundations. His passion for agricultural improvement, transportation infrastructure, and public education demonstrates a forward-thinking approach to nation-building. In Morris, we see not just a signer of a revolutionary document, but a man who spent his remaining twenty-two years ensuring that the promise of that document would endure for future generations.

Thanks for reading!