T.L.D.R. –

- Age at Signing: 42

- Occupation: Lawyer

- Key Perspective/Position: Last to sign

- Personal Sacrifice: Served two states

- Unique Contribution: Later PA governor

Introduction

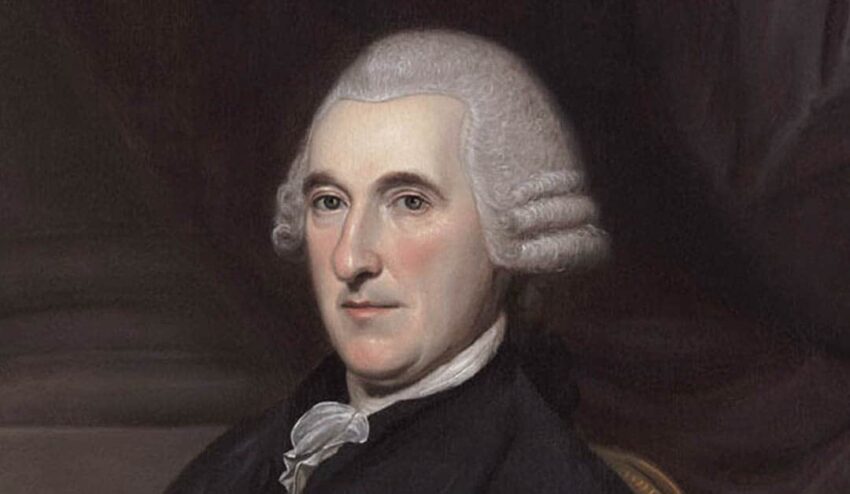

Thomas McKean was born on March 19, 1734, in Chester County, Pennsylvania, the son of an innkeeper and farmer. Though born in Pennsylvania, he studied and practiced law in Delaware. He married Mary Borden in 1763 and later Sarah Armitage, having eleven children total.

McKean held offices in both Delaware and Pennsylvania simultaneously, representing Delaware at the Stamp Act Congress in 1765. He helped dissolve British control in Delaware and ensured, with Caesar Rodney, Delaware’s support for independence. He was the last member of the Second Continental Congress to sign the Declaration.

After serving as a colonel in the Revolutionary War and President of the Continental Congress, McKean became Chief Justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court for 22 years, supporting judicial review principles. He helped secure Pennsylvania’s ratification of the Constitution and served three terms as Pennsylvania’s governor, surviving political opposition and attempted impeachment. At age 80, he helped organize Philadelphia’s defense during the War of 1812. He died on June 24, 1817, at age 83.

Contribution to Independence: McKean’s dual-state influence helped secure support for independence in both Delaware and Pennsylvania. As the last to sign the Declaration, he demonstrated that commitment to independence extended beyond the initial moment.

A Brief Biography

Thomas McKean was born on March 19, 1734 in New London Township, Chester County in Pennsylvania, the son of William McKean and Letitia Finney. His parents were of Ulster-Scots heritage, and emigrated to Pennsylvania as children.

The McKean family ancestry shows an interesting progression, from Scotland to Ireland to America. Thomas McKean’s great-great-great grandfather, William McKean, of Argyleshire, Scotland sought refuge in Ireland in the late 1600s because of religious and political persecution. His son, John McKean, a loyal defender of Londonderry in 1668-1669, died at Ballymony, Ireland. Thomas McKean’s grandfather, William McKean, came with his wife Susannah and family from Londonderry and Ballymony in 1725, and settled on a 300-acre plantation in Chester County.

Thomas McKean’s father, William McKean, was born about 1705, married Letitia Finney of New London and died in 1769. He was an innkeeper in New London, and moved to the Logan plantation with his second wife where he kept a tavern until his death.

Thomas McKean’s mother, Letitia Finney, was the daughter of Robert and Dorothea Finney, who emigrated from Ireland with their family and settled in New London Township before 1720. Robert purchased a plantation there in 1722 and named it Thunder Hill. Thomas McKean received his basic education at home until age nine. At this time, he and his 11-year-old brother, Robert, were sent to continue their education under the tutelage of Rev. Francis Allison at the New London Academy.

After completing his studies, Thomas went to Newcastle, Delaware to study law under his cousin, David Finney. Some months later he was appointed as a clerk to the prothonotary of the Court of Common Pleas. Through his hard work, talent, and industriousness, he was admitted as an attorney in the Court of Common Pleas to Newcastle, Kent, and Sussex before attaining the age of 21. He subsequently was admitted to the Supreme Court also.

By the time he reached his majority, Thomas McKean was over six feet tall. Frequently, he was seen wearing a large cocked hat, fashionable at the time, and was never without his gold-headed cane. It is said that he had a quick temper and a vigorous personality. He had a thin face; hawk’s nose and his eyes would be described by some as ‘hot.’ Some wondered at his popularity with his clients as he was known for a “lofty and often tactless manner that antagonized many people.” He tended to be, what some might describe as a loner, seldom mixing with others except on public occasions.

John Adams described him as “one of the three men in the Continental Congress who appeared to me to see more clearly to the end of the business than any others in the body.”

Both as Chief Justice and later as Governor of Pennsylvania he could be found at the center of several controversies. Not wanting to be over burdened with his studies, Thomas on December 28, 1757 elected to join the Richard Williams company of foot. He would later rise to the rank of Colonel in the militia. At this time, most officer ranks were voted on by the individual militia members and not necessarily by military accomplishments.

Thomas McKean was admitted to the bar in 1754 and soon became deputy attorney general and clerk of the Delaware assembly. In 1758, McKean traveled to London to further his legal studies at the Middle Temple. Returning to America, McKean was elected to the House of Assembly from New Castle in 1762 and served there until 1780. He was Speaker of the Assembly from 1772 to 1779. During these years, he was also appointed Judge in the Court of Common Pleas.

In July 1765 as a judge for the Court of Common Pleas, he established the ruling that all court proceedings of the court be recorded on un-stamped paper. This is one of the several changes in the courts and Continental Congress he would affect during his life. Each change would have long lasting effects on the country.

In 1763. Thomas married Mary Borden, his first wife. From this marriage, they had six children. She died in 1773 and is buried at Immanuel Episcopal Church, New Castle. A year later, he took Sarah Armitage as his second wife. They lived in Philadelphia and had four children.

Recognition of McKean’s growing stature in the colonies began in 1763 when he received an honorary MA degree from the College of Pennsylvania. In 1766, Governor William Franklin of New Jersey admitted McKean to practice law in any of the New Jersey courts, on the recommendation of the New Jersey Supreme Court. And in 1768, he was elected to the American Philosophical Society, a distinguished intellectual society founded by Benjamin Franklin. In 1769, McKean became a trustee of the Academy of Newark, the successor to Allison’s school at New London. He received honorary degrees from Princeton in 1781, Dartmouth in 1782, and Pennsylvania in 1785.

Thomas McKean and Caesar Rodney were appointed delegates to the Stamp Act Congress in 1765. It was here that Thomas made another far-reaching proposal–to change the voting procedure in existence at the time. His proposal was later adopted by the Continental Congress and continues to this day in the United States Senate. His proposal was that no matter the size or population of a colony, each one would get an equal vote.

During the last day of the above congress, several members of the body refused to sign the memorial of rights and grievances. He rose from his seat asking why the President, Timothy Ruggles, refused to sign the document. In the ensuing debate, Ruggles said, and I quote, “… it was against his conscious.” The orator that he was, McKean disputed and challenged his use of the word ‘conscious.’ He issued a challenge to Ruggles, and a duel was accepted and witnessed by the whole body. No duel ever took place as Ruggles left early the next morning. Ruggles, now disgraced, fled back to Massachusetts where he became a leading Tory. He later moved to Nova Scotia.

McKean was appointed a delegate to the First Continental Congress in 1774, and continued in Congress until the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783. He signed the Articles of Association in 1774 and the 1775 Olive Branch Petition seeking reconciliation with King George III. McKean served on many of the committees of the Congress.

In late June 1776, when the debate for independence began, Caesar Rodney was absent, having returned home to Delaware. With George Read against it, McKean sent a dispatch to Rodney requesting he ride all night, if necessary, to break the tie, as Rodney was in favor of independence. Rodney arrived in time for Delaware to vote for independence on July 2, and for the Declaration of Independence on July 4.

The next day, July 5th, McKean, now a Colonel in the associated militia, marched with his men to Perth Amboy to assist Washington in the defense of New York. In a letter dated July 26th, he described a narrow escape of his life from cannon fire. By current road travel, it is approximately 75 miles from Philadelphia to Perth Amboy, a good hard day’s ride at the time. As a descendent of Thomas McKean, I was always told that he did not sign the Declaration of Independence until years later in 1781. It was only through doing the research for this biography that I learned that he may have signed on the same day as the others present on August 2, 1776.

There are differences of opinion as to when Thomas McKean signed the Declaration of Independence. Many historians maintain that he was the 56th and last delegate to sign, possibly 1777 or even later.

But there is contrary evidence. The original copy of the document was deposited with the Delaware secretary of state but when the printed copy was released, McKean’s signature was found to be missing, in both the 1777 and 1800 editions. I would now like to refer you, good reader, to a letter written in Thomas McKean’s own hand to Mr. Alexander J. Dallas of Pennsylvania. The letter is dated 26th September, 1796 and was subsequently published in ‘Sanderson’s Lives’. I quote in part-

“My name is not in the printed journals of congress, as a party to the Declaration of Independence, as this, like an error in the first concoction, has vitiated most of the subsequent publications; and yet the fact is, that I was a member of congress for the state of Delaware, was personally present in congress, and voted in favor of independence on the 4th of July 1776, and signed the declaration after it had been engrossed on parchment, where my name, in my own hand writing, still appears.”

It continues …

“… that on the 19th day of July, 1776, the congress directed that it should be engrossed on parchment, and signed by every member, and that it was so produced on the 2nd of August, and signed. This is interlined in the secret journal, in the hand of Charles Thompson, the secretary. The present secretary of state of the United States, and myself, have lately inspected the journals, and seen this. The journal was first printed by Mr. John Dunlap, in 1778, and probably copies, with the names then signed to it, were printed in August, 1776, and that Mr. Dunlap printed the names from one of them.”

In this, McKean seems to have been mistaken, since most historians believe that only 50 delegates signed the Declaration on August 2, with documented evidence that the remaining six signed in the months following, and is so stated in the history of the period by the National Archives.

On July 28th, 1777 McKean received from the supreme executive council the commission of chief justice for Pennsylvania. He was to hold this position for the next 22 years, until 1799. To show the impact Thomas McKean had on the judicial system, biographer John Coleman commended him as follows:

“Only the historiographical difficulty of reviewing court records and the other scattered documents prevents recognition that McKean, rather than John Marshall, did more than anyone else to establish an independent judiciary in the United States. As chief justice under the Pennsylvania constitution he considered flawed, he assumed it the right of the court to strike down legislative acts it deemed unconstitutional, preceding by ten years the US Supreme Court’s establishment of the doctrine of judicial review. He augmented the rights of defendants and sought penal reform, but on the other hand was slow to recognize expansion of the legal rights of women and the process in the state’s gradual elimination of slavery.”

McKean helped frame Delaware’s first constitution in 1776, but because of loyalist opposition, McKean was not re-elected to Congress from Delaware. In 1777, he became Chief Justice of Pennsylvania, but retained some offices in Delaware for the next six years.

One of the few controversial marks against McKean, during his 20-plus years as Chief Justice, occurred in 1788. The incident occurred between him and Eleazer Oswald. Oswald, in an editorial in the newspaper where he was editor, tried to prejudice the people for him and against the court, Oswald being the defendant in the case. In the editorial, he cast the justices in a very unflattering light. Incensed at Oswald’s accusations, the justices fined him 10 pounds and sentenced him ‘to be imprisoned for a space of one month, that is, from the fifteenth of July to the fifteenth of August.’ At that time, a month was 28 days, so Oswald demanded his release by the sheriff. The sheriff, not knowing what to do, consulted McKean. McKean, not aware the sentence was for “the space of one month” ordered the sheriff to detain the prisoner until August 15th. Upon learning of his mistake, McKean then reversed himself, ordering Oswald freed.

On September 5, 1788 Oswald petitioned the General Assembly where he started the proceedings against him. He then complained to the august body of the decision against him, specifically pointing the finger to the Chief Justice, Thomas McKean, and the sheriff. The House as a whole, held a hearing for three days. Several motions, one of which was made by a Mr. Finley, were offered against the justices, maintaining that they had exceeded their constitutional powers. In the process Oswald asked that the Assembly ‘define the nature and extent of contempt.’ Mr. William Lewis, for the judges, said that the legislature was confined to making the laws, thereby they, the Assembly, cannot interrupt said laws. That was the purview of the justices. He continued by saying that any recommendations by the Assembly would be negated as the ‘courts of justice derive their power from the constitution, a source paramount to the legislature, and consequently what is given to them by the former cannot be taken away by the latter.’

The motion of impeachment set forth by Mr. Finley lost by a considerable margin.

On July 10, 1781 McKean was elected President of the Continental Congress and served until November 4, 1781. This presented an interesting dilemma. The Constitution of Pennsylvania forbade the holding of two offices at the same time. It was decided that this did not apply to holding offices outside the State, since he was a member of Congress from Delaware and Chief Justice from Pennsylvania. It was also learned that several others were holding multiple offices.

Three years after the peace treaty was signed with Great Britain, the Constitutional Convention was convened on May 14, 1787 to amend the Articles of Confederation. Several months later on September 17th, the convention adjourned having settled on an entirely new Constitution. The Constitution was presented to the thirteen states for ratification, and McKean was appointed to the Pennsylvania Ratification Convention. On the 23rd he moved that the document be read in full, and repeated the request on the 24th.

In a short speech to the assembled members, he said they were going into territory never gone before, but advanced the following motion:

“That this Convention do assent to, and ratify, the Constitution agreed to on the seventeenth of September last, by the Convention of the United States of America, held at Philadelphia.”

McKean eloquently argued in favor of the passage of the constitution concluding his speech with these words:

“The objections of this constitution having been answered, and all done away, it remains pure and unhurt; and this alone as a forcible argument of its goodness * * * * The law, sir, has been my study from my infancy, and my only profession. I have gone through the circle of offices, in the legislative, executive, and judicial departments of the government; and from all my study, observation and experience, I must declare that from a full examination and due consideration of this system, it appears to the best the world has yet seen.”

Even though there was some public opposition to the constitution, and at one point both McKean and James Wilson were burned in effigy, the majority of the Pennsylvania Convention approved the document, and Ratification by most of the States was completed by June of the next year. McKean framed the new Pennsylvania constitution in 1790.

Honors continued to be bestowed on Thomas McKean. He received honorary degrees from Princeton in 1781, Dartmouth in 1782 and Pennsylvania in 1785.

On December 17, 1799 McKean stepped down as Chief Justice of Pennsylvania and was elected Governor of that state. He held the office until December 20, 1808 when he retired from public office. As Governor he removed his political enemies from office, but was re-elected twice, in 1802 and 1805.

On June 24, 1817, at the age of eighty-three, Thomas McKean died. At the time of his death, only five other signers of the Declaration remained alive. His remains were interred at the First Presbyterian Church, Market Street, Philadelphia, and later removed to the family vault at Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia.

Thomas McKean’s gravesite received a plaque dedication by the DSDI Society on April 16, 2005.

Credit here for the detailed biography.

Final Thoughts

Looking at Thomas McKean’s life, one cannot help but be struck by the extraordinary balancing act he maintained throughout his career. Here was a man who simultaneously held offices in two states, served as both a military colonel and a chief justice, and managed to be both the last to sign the Declaration of Independence and one of the most influential in shaping the new nation’s legal framework. His dual-state influence proved crucial at pivotal moments—particularly when he urgently summoned Caesar Rodney to break Delaware’s tie vote for independence. This ability to work across boundaries, both geographical and political, exemplified the kind of flexible leadership the young nation desperately needed.

McKean’s judicial legacy deserves particular recognition, especially his pioneering work in establishing judicial review—a full decade before John Marshall’s famous Marbury v. Madison decision. As Pennsylvania’s Chief Justice for 22 years, he transformed the American understanding of an independent judiciary, asserting the courts’ right to strike down unconstitutional legislation. His ruling that court proceedings continue on unstamped paper during the Stamp Act crisis demonstrated his willingness to challenge British authority through legal means. Though his temperament was described as difficult—with his “lofty and often tactless manner”—this same uncompromising nature allowed him to stand firm on principles that would shape American jurisprudence for centuries to come.

Perhaps most remarkably, McKean’s story illustrates how the American Revolution was not just a moment but a lifetime commitment. From his early days challenging the Stamp Act Congress’s voting procedures to defending Philadelphia during the War of 1812 at age 80, McKean devoted nearly six decades to public service. His journey from the son of an Ulster-Scots innkeeper to one of the most powerful figures in early American government embodied the revolutionary promise of merit over birthright. While history may remember him as the last to sign the Declaration, his true significance lies in being among the first to envision and build the legal and governmental structures that would sustain the republic long after the ink on that famous document had dried.

Thanks for reading!