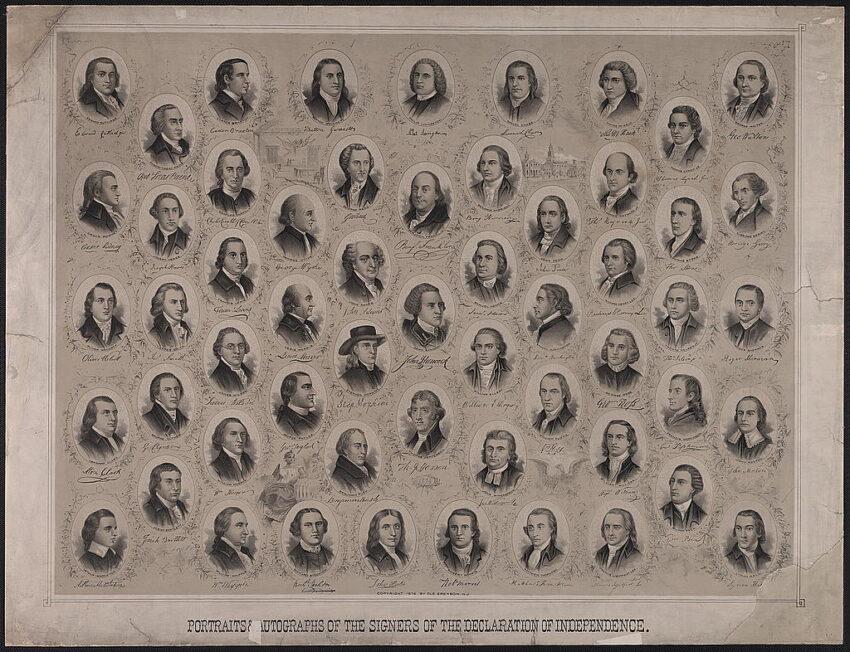

The 56 men who signed the Declaration of Independence risked their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor for the cause of American liberty. They ranged in age from 26 to 70, came from diverse backgrounds, and would pay varying prices for their courage.

Who were these brave men?

The Signers Of The Declaration Of Independence

See below the signers of the Declaration of Independence organized by state, with a link to the biographies of each individual.

Connecticut

Delaware

Georgia

Maryland

Massachusetts

New Hampshire

New Jersey

New York

North Carolina

Pennsylvania

- George Clymer

- Benjamin Franklin

- Robert Morris

- John Morton

- George Ross

- Benjamin Rush

- James Smith

- George Taylor

- James Wilson

Rhode Island

South Carolina

Virginia

- Carter Braxton

- Benjamin Harrison

- Thomas Jefferson

- Richard Henry Lee

- Francis Lightfoot Lee

- Thomas Nelson Jr.

- George Wythe

Patterns Among The Signers

The signers of the Declaration represented a cross-section of colonial society united by their willingness to risk everything for independence. Their diverse perspectives—from Franklin’s worldly wisdom to Rutledge’s youthful passion, from Carroll’s Catholic faith to Witherspoon’s Presbyterian ministry, from Morris’s wealth to Clark’s common touch—created a document that spoke for all Americans, not just the elite. Their personal sacrifices validated their pledge of “lives, fortunes, and sacred honor,” proving these were not mere words but a covenant sealed with their signatures and, for many, their blood.

The Diverse Paths To Revolution

One of the most striking patterns is the sheer diversity of backgrounds among the signers. From Button Gwinnett’s failed English merchant ventures to George Taylor arriving as an indentured servant, from Charles Carroll’s European refinement to Abraham Clark’s role as “the poor man’s counselor,” the Declaration brought together men from vastly different circumstances. This diversity was not incidental but essential—the Revolution succeeded because it united the educated elite like Jefferson with self-made men like Sherman, wealthy merchants like Hancock with frontier surveyors like Clark.

Age Distribution: Ranged from 26 (Rutledge and Lynch) to 70 (Franklin), with most in their 30s-40s

Occupational Diversity: Lawyers (25), merchants (12), planters (10), physicians (4), with some overlapping roles

The Resistance To Change & Paradox Of Principles

Perhaps most fascinating is how many signers initially opposed independence. George Read voted against it before signing. Robert Morris considered it premature. John Dickinson refused to sign at all. Even Franklin spent years seeking reconciliation. Their eventual embrace of independence reveals that the Revolution was not a foregone conclusion, but the result of accumulated grievances, failed negotiations, and gradual realization that separation was inevitable. Men like Joseph Hewes, who suddenly declared “It is done! and I will abide by it,” capture the profound internal struggles that preceded this collective leap into the unknown.

The most troubling pattern found is the contradiction between the ideals proclaimed and the lives lived. Men who declared “all men are created equal” owned hundreds of enslaved people. The same generation that fought against “taxation without representation” denied representation to women, the enslaved, and the landless. Yet within this hypocrisy lay the seeds of progress—their words created standards by which they and their society would eventually be judged and found wanting. George Wythe freeing his slaves, William Whipple’s principled stance on emancipation, and even Jefferson‘s tortured recognition of slavery as a “fire bell in the night” show how these contradictions gnawed at some of their consciences.

The Cost Of Sacred Honor

The pledge of “lives, fortunes, and sacred honor” was no mere rhetoric. The personal sacrifices were staggering: Richard Stockton tortured in prison, Francis Lewis’s wife dying from British captivity, Thomas Nelson Jr. ordering cannon fire on his own home, John Hart hiding in caves while his farm was destroyed. At least nine signers died during or shortly after the war, many impoverished. Robert Morris, the financier of the Revolution, died in debtor’s prison. Carter Braxton lost his shipping empire. These were men who had everything to lose and chose to risk it all.

Nearly all suffered property loss, imprisonment, or family tragedy. Several died young (Lynch at 30, Gwinnett at 42, Morton at 53) or in poverty (Nelson, Morris)

The varying fates of the signers remind us how history’s memory can be arbitrary. While Jefferson, Franklin, and Adams became immortal, men like George Taylor, William Whipple, and Matthew Thornton faded into obscurity – despite equal courage and sacrifice. Some, like Button Gwinnett, achieved fame only through the rarity of their signatures. This disparity teaches humility about historical memory and the countless unnamed patriots whose contributions made independence possible.

The Architecture Of A New World

Beyond their signatures, these men built the scaffolding of a new nation. They didn’t just declare independence; they had to create it. James Wilson architected the Constitution. George Wythe trained the next generation of leaders. Robert Morris created financial systems. John Witherspoon shaped educational institutions. Benjamin Rush revolutionized medical care. Francis Hopkinson designed national symbols. They understood that revolution required not just destroying the old order but constructing something unprecedented in human history.

Perhaps the most important insight is that these men began something they could not complete. They created a framework—imperfect, contradictory, but expandable. The Constitution they debated, the institutions they built, the ideals they articulated all contained within them the capacity for growth and self-correction. Their declaration that governments derive “their just powers from the consent of the governed” set in motion forces that would eventually extend far beyond what most of them imagined or intended.

The Power Of Networks & Collective Action

The interconnections among the signers reveal how personal relationships drove political change. The Adams cousins reinforcing each other’s resolve, the Lee brothers providing Virginia’s crucial support, Franklin mentoring so many younger patriots, marriage connections like Rush and Stockton—these networks created resilience when individual resolve might have faltered. The Revolution was as much a social movement as a political one, sustained by bonds of friendship, family, and shared sacrifice.

Each signature represented an individual act of courage that gained meaning only through collective action. Stephen Hopkins’s palsied hand trembling as he signed, Charles Carroll adding “of Carrollton” to ensure no mistaking his identity, John Hancock’s defiant flourish—these individual moments created an unstoppable collective force. They show how history hinges on personal choices that compound into world-changing events.

Final Thoughts On The Signers

Looking back on this journey through the lives of the 56 signers of the Declaration of Independence, I realize that these were not mythic figures born to greatness, but flesh-and-blood individuals who made extraordinary choices in extraordinary times – ordinary people, flawed and conflicted, that rose to meet history’s demands and change the world.

That is perhaps their greatest legacy: not what they created, but the proof that imperfect people can still pursue perfect ideals, and in that pursuit, bend the arc of history toward justice.

Thanks for reading!